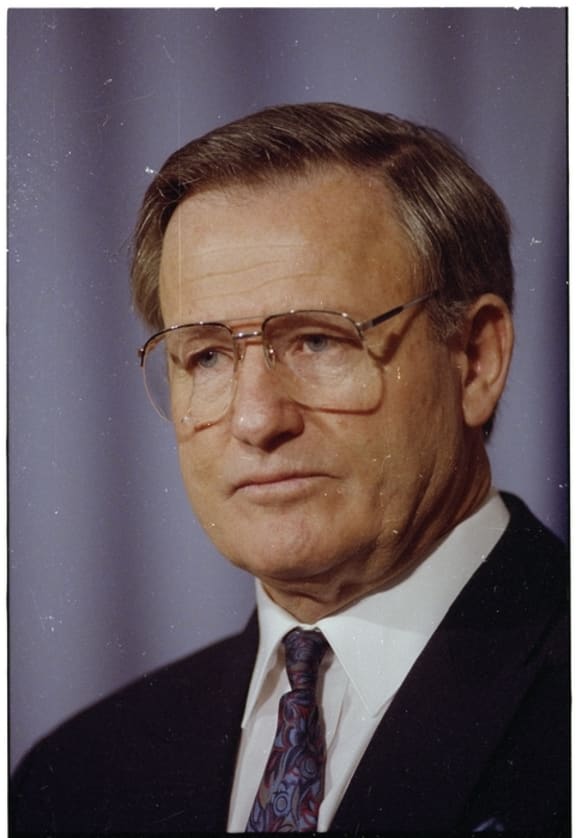

In a new episode of RNZ's Eyewitness podcast, Sir Jim McLay tells Justin Gregory about the day he faced down the most dominant politician in living memory.

Subscribe to Eyewitness for free on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

Photo: Fairfax

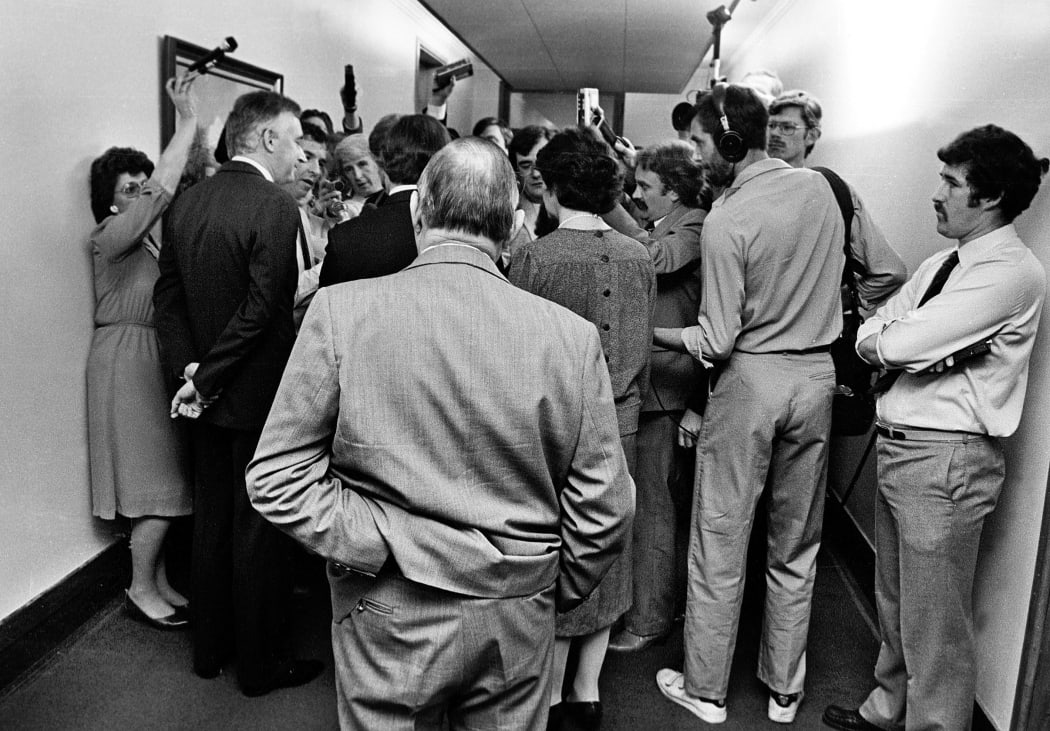

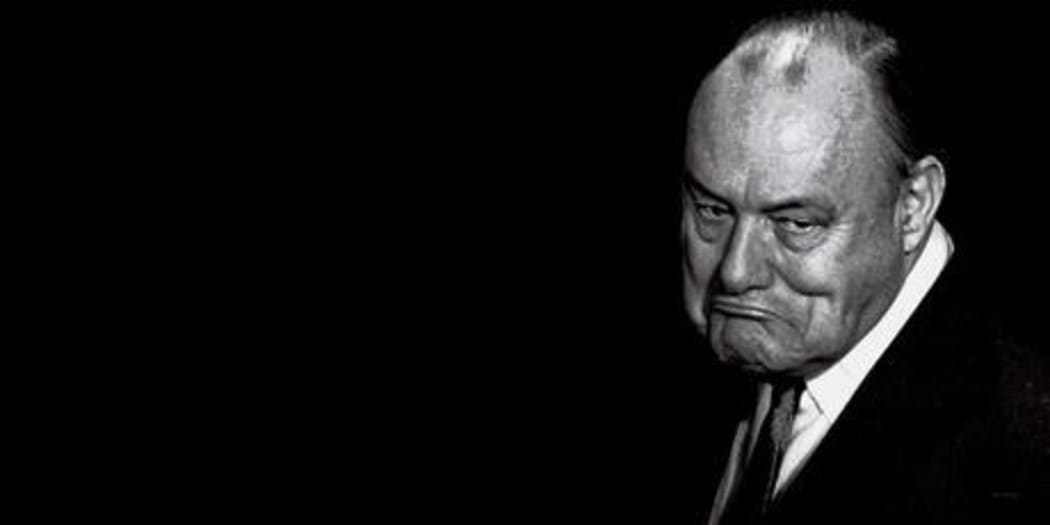

Late on the evening of 14 June 1984, National Party Prime Minister Sir Robert Muldoon walked unsteadily down a corridor in Parliament towards waiting journalists. He stared glassily into a TV camera and announced that the country would go to the polls early.

The date he chose for the snap election was 14 July, just four weeks away. RNZ journalist Richard Griffin suggested it didn't give Muldoon's party much time to run up to an election. The Prime Minister slurred a famous reply.

For nearly a full parliamentary term, Sir Robert had led a government with just a single seat majority. When National backbencher Marilyn Waring announced she would vote against her party on certain issues, Muldoon decided he couldn't continue on that basis.

Sir Robert Muldoon, New Zealand prime minister 1975 - 1984 Photo: Imagebank

Standing just behind Sir Robert that night was Jim McLay. Now Sir James McLay and a senior diplomat, in 1984 he was 39 years-old, the Attorney General of New Zealand as well as Deputy Prime Minister. McLay had been in the job for just a few short months; he and Muldoon had "a very correct relationship. We were not particularly compatible spirits. It wasn't difficult, but it wasn't super-friendly either.”

"We certainly weren't drinking buddies".

For some time, McLay had thought a snap election likely and during the short campaign fully supported his leader. But Labour won in a canter. McLay expected Sir Robert to follow established convention and obey any instructions he might be given during the few days it would take Labour to form a new government.

But McLay was wrong. Instead, a defeated Muldoon dug in his toes on one crucial issue.

For many months prior to the election, the Reserve Bank had been warning Sir Robert that an overvalued NZ dollar was vulnerable to speculation. They recommended a 15% devaluation. Muldoon disagreed.

While Labour didn’t have a clear policy on devaluing the dollar, it was widely believed to be in favour. When the snap election was called, a run on the dollar took place, anticipating a Labour win. Millions of dollars flowed out of New Zealand and the Reserve Bank used up almost all of its foreign currency reserves. The country was in danger of defaulting on its loan repayments.

On Sunday 15 July, the morning after he lost the election, Sir Robert was at his desk in the Beehive when the phone rang. Treasury and Reserve Bank officials wanted a meeting. Muldoon refused. They warned him the foreign exchange could not open for trading the next day without an immediate devaluation. Muldoon replied that they could close the exchange if they liked but that the dollar would stay where it was.

The next day, Sir Robert rang David Lange, asking for a joint press conference announcing they would not devalue. Lange said he needed to meet with Treasury and the Reserve Bank first. After being briefed, he opted for devaluation – but here’s where the trouble starts; no one told Muldoon.

Lange thought the officials who briefed him would inform the Prime Minister of his decision. They thought that was Lange’s job. But they didn't tell him that and no one told Muldoon anything.

On the news that night a frustrated Lange, believing Muldoon had been briefed but not having heard from him, claimed the Prime Minister was refusing his advice. This infuriated Muldoon, who had waited all day in his office for a phone call that never came. He immediately went on TV with reporter Richard Harman to argue that the New Zealand dollar was only under pressure due to the election. It would bounce back, he claimed, as soon as the election was over. All it would take was the joint press statement he had suggested to Lange.

"And that's it!"

Then Sir Robert uttered those fateful words.

"I am not going to devalue so long as I am Minister of Finance!"

"If Mr Lange has got any sense at all, and up until this moment on this thing, he has not displayed it, he will come out with me and say 'we will not devalue the New Zealand dollar!"

David Lange bit back.

"I say we have now reached the point where there is a constitutional crisis."

Lange called Muldoon "beaten", accused him of economic sabotage and ridiculed his call for a joint statement as "nonsense". He said Muldoon was not accepting the result of the election and was “wallowing in political point scoring.” Lange could do no more until the Labour Party was sworn in.

"It is time for the National Party to take steps in the interests of this country's economic security to see that he does not exercise that power because clearly now he has passed the capacity to exercise a judgement in the interests of New Zealand."

While all this was going on, Jim McLay was in his Beehive office unaware of the drama unfolding.

“My wife was at home and she rang me and said ‘you should listen to this’. And she literally held the phone up to the TV so I heard what had been said.”

“And I was astonished. In my view, even if it disagreed, an outgoing government had to act on the advice of an incoming administration.”

Muldoon’s refusal to act, meant McLay felt he had to. The tipping point had been reached. Senior National Party MPs began arriving in his office, among them Jim Bolger, Bill Birch and Hugh Templeton. Templeton, who had just lost the supposedly safe National seat of Ohariu to then Labour Party MP Peter Dunne, was so alarmed by Muldoon’s stance that he had run to the Beehive from his nearby home. He was out of office, out of breath and out of Parliament, but still felt a duty to act.

Photo: The Dominion Post / Phil Reid

McLay says there was unanimity that night among those present that their leader’s behaviour was improper and action was required to turn Muldoon around. As a lawyer, McLay’s thoughts turned immediately to the legal position. Was there a constitutional convention that required Muldoon to do what Lange asked?

The answer was no - the issue had never come up before. A kind of gentleman’s agreement meant outgoing governments had always honoured the wishes of the incoming one but legally, if Sir Robert wanted to ignore David Lange he could. McLay hurriedly put together a constitutional argument to the contrary, citing a recent similar situation in Australia.

But it was a bluff. There was no convention. It became clear that there was really only one possible course of action and all eyes in the room turned to the Deputy PM.

The group agreed that McLay would confront Muldoon “at the earliest possible opportunity” and tell him what should be done. If the Prime Minister refused to comply, McLay would go to the Governor General and advise him that Sir Robert had lost the confidence of his senior colleagues and should be removed from office. The Governor General would then appoint McLay as Prime Minister and he would act only on the wishes of the incoming Labour Government.

The plan was sound, tactically and constitutionally. But McLay would have to pay the price.

“My political career was certainly over.”

If Muldoon did refuse and was removed, a leadership contest would follow. McLay said he wanted it made clear that should this occur, he would not stand for the job and would not accept it “under any circumstances.”

“What I didn’t want was anybody suggesting that I had done this out of some sort of personal political motivation. And the only way I could do that was taking myself completely out of the game.”

The group tried to call Sir Robert at home. And again. No answer. It later emerged that the Prime Minister’s wife, Lady Thea, wanted her husband to rest and had taken the telephone off the hook. (Muldoon, unaware, was upstairs with the TV on, watching the gritty police drama Hill Street Blues. He had once said the programme reminded him of the workings of the National Party caucus.)

Tuesday 17 June; McLay, who had not slept, arrived early at the Beehive and asked to see the Prime Minister. The showdown between the urbane Auckland lawyer and our most dominant politician in living memory was on. If you were placing a bet, you might not have put your money on the Deputy Prime Minister.

But you’d have been wrong. By 1984 Muldoon was exhausted, unwell, and had just been defeated in a General Election.

“He’d lost a lot of that lustre, a lot of that political skill.”

McLay was still wary, though, and had a clear idea of how the meeting might go

“He (Muldoon) was still very aggressive.”

Muldoon was shuffling papers on his desk when McLay entered and at first wouldn’t meet his deputy’s eye. McLay told him his colleagues were concerned about what Muldoon had said the previous night. When Muldoon asked McLay who those colleagues were, the younger man ducked the question.

Then McLay played his bluff. He told the Prime Minister a constitutional convention demanded that he abide by the wishes of the incoming government. He must agree to devalue.

For 15 minutes, the two men sparred in what McLay described as a “very aggressive, very unpleasant” exchange. But eventually Muldoon gave in and agreed to the devaluation. In the Cabinet meeting that followed, he presented the change of direction as his own decision.

Photo: Fairfax

McLay rushed out a press release of the convention he had drafted the previous night. It stated that “On occasions, it may be necessary for a government to remain in office for some period on an interim basis…During such periods, the incumbent government is still the lawful executive authority”.

However, “governments in this situation have traditionally constrained their actions…in accordance with what is known as the convention on caretaker government.”

McLay wanted on record what had been agreed to in caucus. That way, he reasoned, Muldoon wouldn’t be able to go back on it.

The devaluation took place and on July 26, 1984 the victorious Labour Party MPs were sworn in as the new government. By the end of November, Sir Robert Muldoon had been rolled as leader of the National Party and replaced by Jim McLay. The former Prime Minister refused all the shadow cabinet positions offered to him and spent the next two years sniping at his new leader from the back benches.

In 1986, Jim Bolger, who had supported McLay on the night of 16 July 1984,executed a coup against him and became National's new leader. Muldoon was returned to the front benches. The following year, Jim McLay retired from politics.

The Right Honourable Sir Robert Muldoon lived long enough to see the National Party win the 1990 election in a landslide. But Muldoon was out of step with the neo-liberal policies of his party and a year later, he retired from politics. On the 5th of August 1992 Rob Muldoon died at the age of 70.

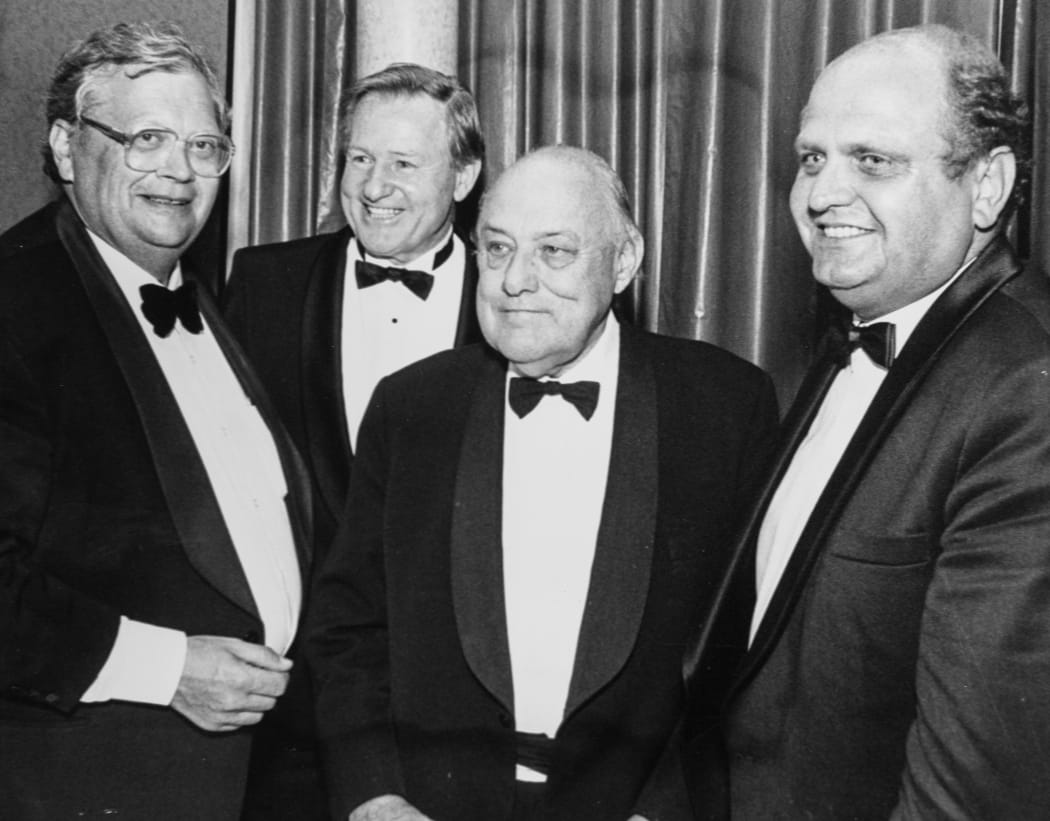

Four New Zealand Prime Ministers - David Lange, Jim Bolger, Sir Robert Muldoon and Mike Moore - at Muldoon's 1992 valedictory dinner, Wellington Club. Photo: Supplied

In the more than 30 years since the 1984 constitutional crisis, the Honourable Sir Jim McLay has led a highly successful career as a diplomat, including time as New Zealand’s Ambassador to the United Nations. In 2015 he was knighted.

Jim McLay speaks at a press conference at the UN in New York to promote the 2015 Cricket World Cup in June 2014. Photo: AFP

McLay’s Caretaker Convention, as it became known, was in time adopted by several Commonwealth nations and is now a part of New Zealand’s official Cabinet Manual. Thanks to him, the kind of constitutional crisis that the nation fell into in 1984 should never happen again. Remarkably, hardly a word has changed from that first hastily written draft.

While the animosity he earned staring down Muldoon undermined his own time as leader, McLay has no regrets about his actions over those three days. He’d do it all over again.

“If I can invoke the Streaker’s Defence, it seemed like a good idea at the time.”

This story was produced by Justin Gregory and uses archival audio from the 1994 TVNZ Frontline documentary Five Days in July. You can subscribe or listen to every Eyewitness podcast on iTunes or at radionz.co.nz/series.

If you have stories you want us to tell, email us at eyewitness@radionz.co.nz.