Online services like Netflix, iTunes and Amazon work out what we like based on what we do online.

News websites know what we have read and shared, but not what we might want next. Mediawatch meets a scientist who joined a newsroom to fix that.

Photo: AFP

Last Monday, the US headquarters of the big beast in global video-on-demand - Netflix - sent out this tweet:

To the 53 people who've watched A Christmas Prince every day for the past 18 days: Who hurt you?

— Netflix US (@netflix) December 11, 2017

Some found that funny - judging by all those 'likes' but others thought it was downright mean to call out the binge-watching habits of a handful of customers like that.

It was also a reminder that while more than 100 million people watch Netflix - including more than a million households in New Zealand - Netflix watches them.

Netflix first became a huge player by making shows and movies available online and now makes its own ones. (A Christmas Prince is one of them).

A key factor in their success is the data provided by its viewers themselves.

A recent New Zealand Herald article headed 'has Netflix changed TV forever?' explained it like this:

"Where once, film and television companies relied on test screenings and focus groups to gauge audience reaction, Netflix feeds off vast amounts of data on the viewing habits and tastes of its subscribers; it classifies its shows and films using about 77,000 individual "micro-genres" - and commissions more programmes that fit into the most popular ones."

Once Netflix has done that, it lets the right customers know when it's available.

Retailers like iTunes and Amazon also prompt their customers with variations of: “if you liked this; you might like these.”

But for broadcasters and news media outfits operating online, this is harder to do. Satisfying people’s demand for compelling content every day is tougher than selling them a book or a movie once in a while.

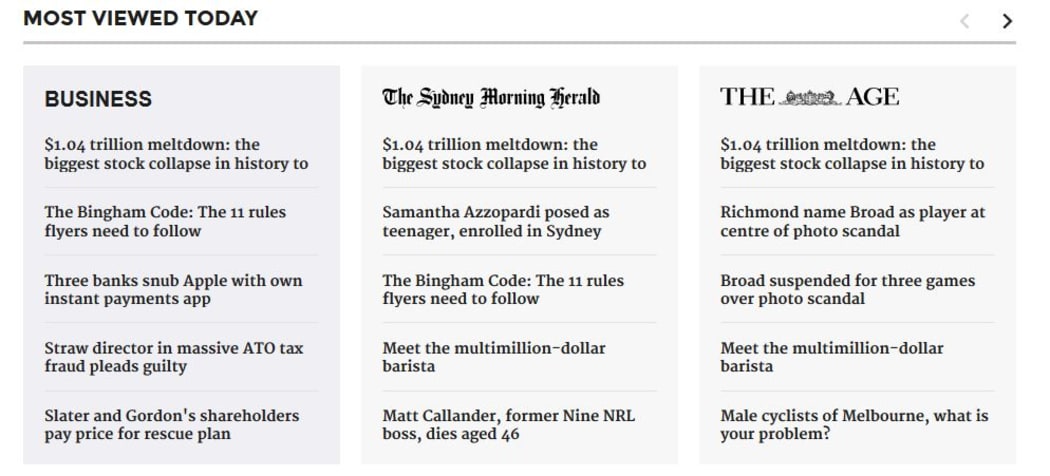

Those lists of 'most read' and 'most shared' stories can show what people have been looking at and the 'related stories' links might be of interest, but it’s much harder for them to work out what people might want to read or watch next.

What recommendation engine picks from the web. Photo: screenshot

Leading digital news media thinker Frederick Filloux said no news media company was able to invest US$20m a year to design a recommendation engine as Netflix had done, or have 70 digital engineers working on it.

Online opportunists seeking to fill the gap so far haven't really helped.

When you scroll down some news websites to the bottom you might find a set of stories tagged 'recommended for you' from recommendation engines like Taboola or Outbrain.

Mr Filloux described these as “a horror show” and the "worst visual polluters of digital news."

"In most cases, they send the reader to myriads of clickbait sites. This comes with several side-effects: readers go away, and it disfigures the best design," he said.

"Repeatedly direct your reader toward a shallow three-year-old piece, and it’s highly likely she might never again click on your suggestions," he added.

Most popular, most shared, most viewed lists on news websites don't reveal much about what individual readers might want next. Photo: screenshot / smh.com.au

He’s currently at Stanford University working on something better: the News Quality Scoring Project, which he said will use machine learning to highlight quality journalism online - and not stale paid-for clickbait.

Closer to home, a New Zealand-born biophysicist based in Sydney has also been working on something better for the media.

In 2012 Dr Matt Baker joined the Australian Broadcasting Corporation as scientist in residence and in 2016 he was embedded at the Sydney Morning Herald to point its readers to stories online that are relevant to them.

So how did he work out what they might want to read next?

Matt Baker Photo: supplied

"The crudest way of doing it is to look at the 'most viewed' but a better way is looking at who's reading selected articles and offer five articles most similar to the one you are reading," he said.

'Related stories' links don't always help, he said, if the reader had already read those stories.

"If you can recommend three things they haven't read, that can be a win for the reader and the publisher."

Dating sites work in a similar way, he said.

Different sort of preference surely?

"Yes - but the same sort of mathematics," he replied.

"Computationally you can say these articles are probably similar - and you can (find) cases a human might not do."

"People might read a couple of rugby articles and then a business article. A human looks at that and says: "That's a rugby article. Serve them another rugby article.' The computer is looking at tens of thousands of articles and it's able to say which one of these is most similar to the one they're reading now.

"Some people are pushing for free-form pages for websites where there are no topics. It's customised based on the user and it flows based on things it knows about you and your region."

He said that only worked really well if users were logged in, which many were still reluctant to do.

And maybe for good reason.

"One of the things that's good about traditional newspapers and magazines is serendipity. You don't know what you're going to get when you turn the page. A human has curated that content in that order and in that space.

"Recommendations being served to you digitally means you get less of that. Sprinkling a bit of magic randomness in there retains a bit of serendipity and that's quite powerful because it delivers new information to people who may not have been looking for it."