Little is known about the Japanese war brides who married New Zealand soldiers stationed in Japan as part of the occupying force after World War II. They were young women who survived the atomic blast that destroyed Hiroshima and their homes there, but then fell for soldiers from an army they had been at war with just a few years before.

Some were cut off by their families, and in New Zealand often found themselves alienated again. That’s Taeko Yoshioka Braid’s story – a story of love and loss that runs from Hiroshima to Hastings – and one that’s only come to light thanks to new research from a Unitec MA student.

Subscribe to Voices for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher andRadio Public or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

Mutsumi Kanazawa has good reason to be interested in Japanese war brides. Her mother was only 3km from the epicentre when the atomic blast from a US bomb destroyed Hiroshima; she spent the rest of her life suffering from radiation sickness.

Mutsumi recalls growing up in post-war Hiroshima, wondering why her mother was not a war bride too, and why she was not a child of a soldier. She couldn’t ask her mother about the traumatic experiences of the war, but years later, while researching Japanese immigrants in New Zealand she discovered women with stories close to her heart.

By then Mutsumi had embarked on her own trans-Pacific voyage from Japan to Auckland, she began her study in 2013.

“I didn’t know that Kiwi soldiers were in Japan after the war. The place they were in was Kure, Hiroshima where my mother was born.”

It turns out as many as 50 war brides had come to New Zealand, all from around Hiroshima and all around the same age as her mother.

Her Master’s thesis at Unitec, Auckland, aims to preserve the stories of Japanese war brides; women who were “disowned, dislocated and then discovered,” according to Mutsumi.

“Many were disowned by their families because of their association with former enemy soldiers.”

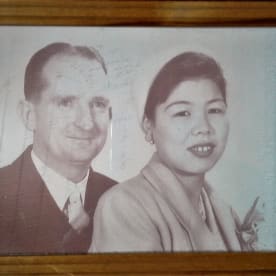

Taeko Yoshioka Braid c 1937-8. Photo courtsey Yoshioka family. Photo: Yoshioka family

Japanese regulations forbade citizens from travelling overseas until 1964, but the war brides were able to leave Hiroshima earlier when their husbands were shipped home.

“Once the women left Japan, most of them felt there would be no turning back. They were so isolated because they didn’t speak English, so they couldn’t get a job outside of their house.”

Only a dozen or so women remain alive today but many don’t want to talk of their experiences.

“There was stigma attached to the war brides.”

Taeko Yoshioka Braid, however, is happy to share her extraordinary story. She and the son and daughter of another war bride feature in Mutsumi’s research.

Taeko tells me in broken English that her name means ‘funny girl'. Born in 1931, her father, a high-ranking official, served in the Japanese Navy. He died when his boat was torpedoed in 1943.

“My father always said I have to learn English and Chinese, because when he was travelling, that three languages very necessary.”

Taeko witnessed the atomic blast that destroyed the city of her birth just before her fourteenth birthday. As the eldest, she became the leader of the family.

“So after war ended, when soldiers coming into Japan, I used to hop into bar. I used to sing a song. Very happy.”

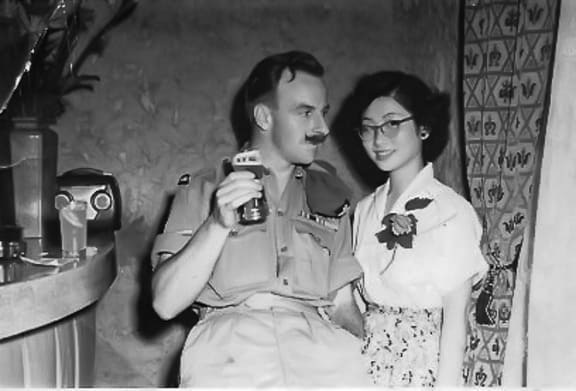

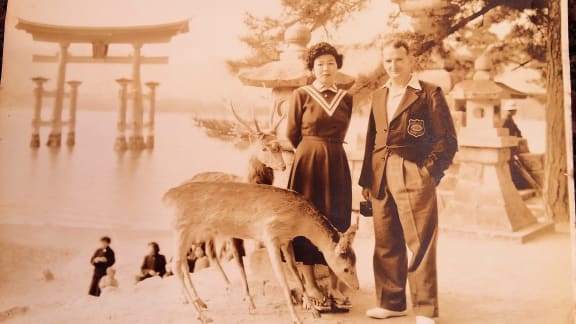

It was in 1950, as an 18-year-old translating and singing in bars to support her sick mother and five younger brothers, that Taeko met Noel (aka ‘Crash’) Braid. He was a soldier with the New Zealand K Force stationed in Kure.

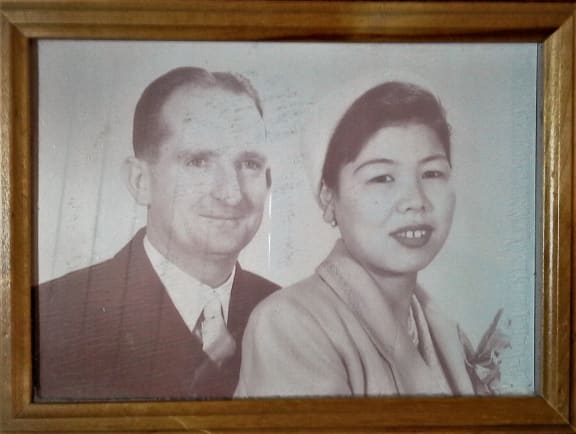

‘Crash’ was Noel’s nickname apparently because of the way he rode motorbikes. He married Taeko in 1952 in Japan. The first ‘lost in translation moment’ came on their wedding day.

“I did not know his name was Noel,” laughs Taeko. “When I saw our marriage certificate, that’s when I find out his name was not ‘Crash!’”

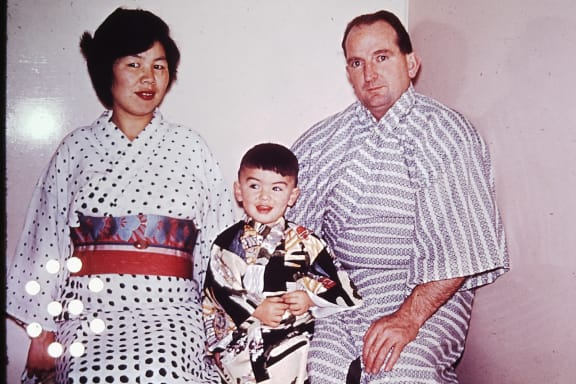

In those post war years, she and Noel ran the “Black Diamond”, a bar for the Commonwealth soldiers. The first of their six children, George, was born there. “Suddenly I was told we go New Zealand.”

Noel was called back home after his father passed away in 1955. Taeko came later with George – a journey from Hiroshima to Hastings that took over a month, as Noel waited in Hawke's Bay for his wife and their four-year-old child.

Taeko Yoshioka Braid and daughter Sonia Yoshioka Braid at RNZ Studios, Wellington. Photo: RNZ Lynda Chanwai-Earle

The culture shock was profound for Taeko when she arrived in 1956. She and George were hardly welcomed. Taeko was only one of two Japanese women living in Hawke's Bay.

“I had a woman live around the corner. She first thought I was Chinese.” When Taeko told her that she was Japanese, the woman went stiff. Her 19-year-old grandson had been killed by the Japanese.

“I told her then and then, I’m sorry to tell you I’m Japanese. I’m sorry, the war is like that.”

Being Japanese in an Allied country meant the shadow of World War II hung over the lives of other war brides, including Setsuko Donnelly, who passed away in 1991. Her children, daughter Deb and son Leo Donnelly shared their mother’s story with Mutsumi.

An Ombudsman at Parliament, Leo recalls growing up in Wellington with a fiercely protective ‘tiger mother’. Setsuko valued education and upheld her Japanese culture with dignity. However, their father Mick Donnelly discouraged their mother tongue Japanese, in the belief it would prevent bullying.

At his father’s funeral a stranger approached Leo, asking if he was Mick’s son. The woman then apologised on behalf of the community, ‘“Your mother was treated really badly”.’

“I remember Mum couldn’t understand what was being said but she knew there was ill feeling,” says Leo.

In spite of adversity, both women worked tirelessly within their communities to become bridges between Japan and New Zealand. Taeko co-founded the Hawke's Bay Japan Society and spent the next decades translating for visiting dignitaries.

Mutsumi says her work is about recognition.

“They were very determined to make a new life in a new land. They didn’t think they had a chance to go back to Japan. They had to make their life happy and successful.”

Taeko Yoshioka Braid has six children, 17 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Pictured here with grandchildren. Photo: Yoshioka Braid Family

Photo: Nga Taonga Sound & Vision