Ashley Bloomfield was left momentarily speechless by a question from The New Zealand Herald’s Jason Walls during Sunday’s Covid-19 media briefing.

“What do you make of suggestions by some leaders overseas that people should be injecting themselves with bleach to kill Covid-19?” Walls asked.

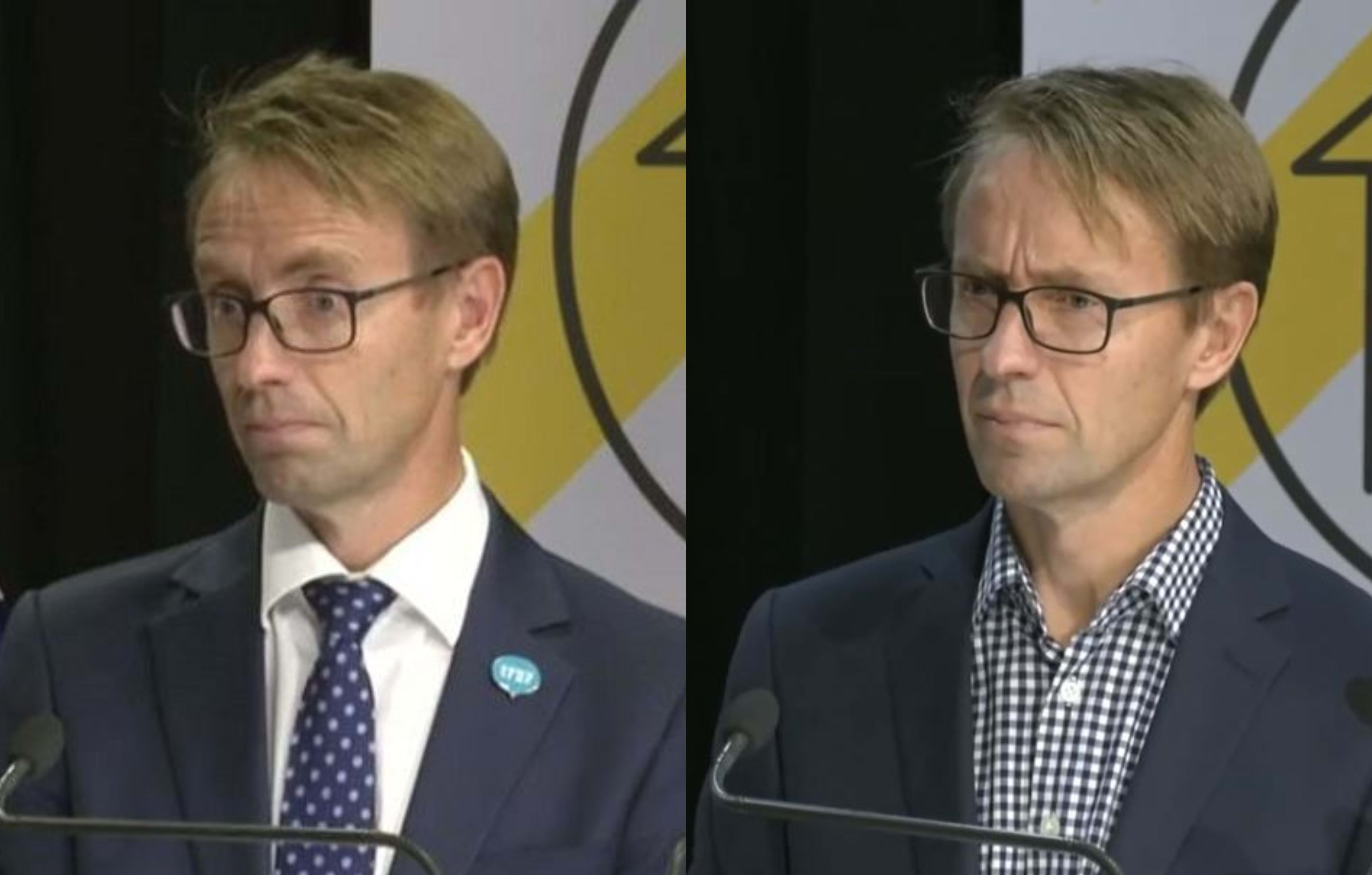

Ashley Bloomfield being asked about 5G conspiracy theories on April 8 vs Ashley Bloomfield being asked about bleach injections on April 26. Photo: Supplied

Bloomfield furrowed his brow and blinked slowly. “I don’t think I need to comment on that,” he said, turning to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern for reassurance.

“No, we’ll let your silence speak for itself,” she replied.

Newshub’s Tova O’Brien took the chance to stick up for Walls. “It is worth asking,” she said. Ardern fixed her with a stern glare and shot back. “Is it?”

The interaction was reminiscent of another exchange from 8 April, when Stuff’s Henry Cooke asked Bloomfield what he made of Instagram influencers claiming 5G was causing Covid-19.

In that case, the director-general of health was similarly incredulous. Again, Ardern took over and answered the question for him.

Both questions attracted some scorn. Cooke, Walls and O’Brien have been criticised on social media by those who feel they shouldn’t raise bad ideas or conspiracy theories during their limited time interrogating our leaders.

“I get why it’s funny, and I really admire their responses, but it’s taking the piss and wasting their time,” one person wrote on Reddit.

“Honestly, the media have limited time and opportunity to ask questions at the press conferences, and some of them are just ridiculous,” another person wrote on Twitter.

Many other comments came in a similar vein.

I wrote in defence of Cooke’s question on 8 April. The idea that 5G causes Covid-19 may be rank nonsense, but it has many real-world adherents, and some of them are causing harm.

When he raised the issue, anti-5G activists had already vandalised cellular infrastructure in the UK, and allegedly closer to home in Northland. Zealots for the cause were out in force on social public media trying to win more followers. Having a credible voice like Ardern or Bloomfield on-the-record rubbishing their ideas could have been enough to sway some potential believers.

A similar logic could apply to Walls’ question. He was loosely referencing the words of US President Donald Trump, who last week mused about the potential curative effects of UV light and disinfectant injections for people with Covid-19. It’s possible some acolytes could have taken his words, extrapolate them out, and done themselves harm.

That has precedent. When Trump talked up hydroxychloroquine as potential treatment for Covid-19, an Arizona couple ingested aquarium cleaner containing the drug. The man died, and the woman ended up in intensive care.

Herald science journalist Jamie Morton pointed to the international coverage Bloomfield’s response received as evidence that Walls’ question was worth asking.

“People bash our press gallery journalists for asking what they think are stupid questions. The Guardian uses the response to one of those “stupid” questions as the basis of an article... shooting down a dangerous and inane idea by the world’s most powerful politician,” he wrote on Twitter.

But that case is less convincing than it was for Cooke’s 5G question. Trump’s comments on disinfectant had been rubbished by health officials and commentators long before they got put to Bloomfield.

The message was also less likely to cause damage in New Zealand than the 5G theories. It may be an indictment on the US political landscape, but the president’s words likely have less effect on behaviour here than the ideas advanced by social media influencers.

Lastly, injecting bleach has a significant inbuilt limit on how far it can spread as an idea, because its most zealous adherents get sick or die. It was unlikely to get much amateur pickup in the Republican heartlands of the US, let alone here where skepticism toward Trump is far higher.

In the words of this clip by the comedian Jane Godley, most people learned not to drink bleach quite young, and don't need to be reminded. (Warning: a lot of swearing.)

This was most likely a benign kind of ‘gotcha’ question. Whether Bloomfield mentioned Trump in his response or not, it could be turned into a headline or social media post about him discrediting the US president.

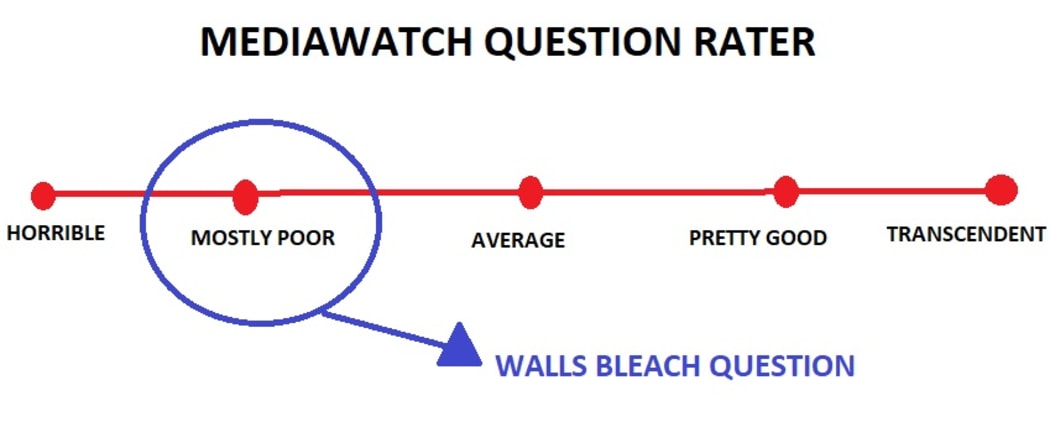

That could generate traffic, which may once have been used to sell ads, but it’s unlikely to have achieved much collective good beside providing us with another Bloomfield reaction video. There’s value in that, but not enough to justify troubling the man in such a profound way. As such, the Mediawatch editorial board has rated Walls’ question ‘mostly poor’.

Photo: Hayden Donnell

Having said that, it’s possible we should calm down a bit. Journalists have experienced regular torrents of abuse since the daily Covid-19 briefings began, with Newshub’s O’Brien faring the worst. The tenor of some of the criticism has been cruel.

Reporters deserve to be scrutinised (even if it means having their questions placed on a reductive, potentially insulting scale by commentators at the public broadcaster). There are real questions to be asked of their work, and that reflection is more important than ever as social media undermines the assumption of widespread public trust that news outlets once enjoyed.

But Walls’ question was one of dozens fielded that day and one of hundreds since the beginning of lockdown.

There are sometimes good reasons journalists ask questions that seem dumb or unnecessary. There are also just times that they’re tired, distracted, forgetful, or in Walls’ case on April 17, all three. That should be understandable.

On Tuesday, Bloomfield fielded another mostly poor question. He was asked whether he was concerned seeing people lining up for fast food on the first day of lockdown level 3.

Instead of answering directly, he talked about how much he’d enjoyed his takeaway coffee that morning. “I don’t want to be preachy on this,” he said, resisting the urge to harshly condemn the KFC-goers.

Bloomfield's background is in non-communicable diseases, and he probably has more professional reason than most to be worried about people's lifestyles. It's notable he paused before rushing to judgement. In that case, as in others, a little bit of empathy and restraint can be laudable.