The career of Professor Richard Thaler blossomed when he realised people do weird things not allowed for by economists.

Last year he won the Nobel Prize for his contributions to behavioural economics, recognising the importance of the follies of human behaviour.

Prof Thaler teaches at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business, and is a key proponent of the idea that humans don't always make rational choices.

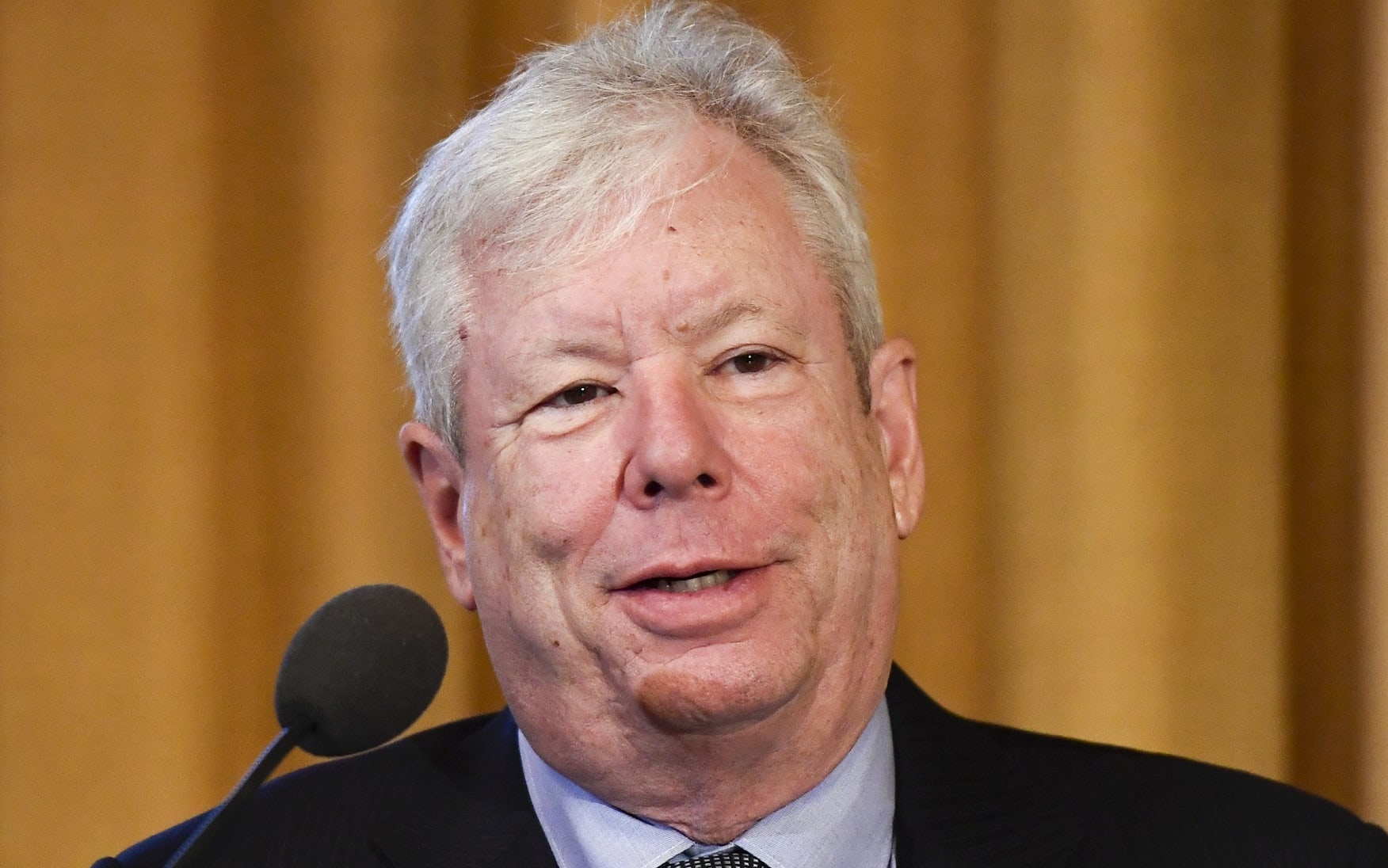

The 2017 Nobel laureate for Economic Sciences, Richard Thaler Photo: AFP

By applying insights from psychological research, Thaler helps us understand people's economic decision-making.

His research makes it clear how much of a gap there is between what economic theory suggests we should do with our money and our investments, and what we do in the real world.

Loss aversion is one quirk of human nature. He says our emotional reaction to a loss is more powerful than to a win.

In the US, in 2008, real estate prices were falling in some places as much as 50 percent.

The interesting thing is, he says, volume also shrivelled. People weren't selling.

"That's a puzzle to economists. But if you paid a million dollars for your house there's no way you want to sell it for $750,000 especially if your neighbour sold his for a million last year.

"That's one way we observe loss aversion in the markets."

Another human foible is the belief in 'hot streaks' "So when real estate prices were going up in the early 2000s in places that were particularly hot - you would hear people say, 'well prices never go down, they only go up."

Thaler is best known for nudge economics. "We coined this term nudge and also this clumsy term 'libertarian paternalism'," he says. "The idea was you could influence people's choices for good without restricting their choices."

An example of a 'good nudge' is people being automatically signed up to superannuation schemes, with the option to opt out.

"If you want to get people to do something, make it easy and automatic enrolment is a good example of that."

He believes technology could save us from the worst of ourselves.

"I don't think that we're getting smarter, that's not the way evolution works. Evolution is very slow, but there's hope, and much of the hope comes from technology.

"Once we recognise that people have these weaknesses … it's possible to devise government programmes to help people do the things they really want to do, but procrastinate or never get around to."

He says one of the ways technology could help is in devising easy-to-use apps that help people budget.

Nudge - 21 August

It's hard to change habits, but a gentle push can move us in the right direction.