Ry Cooder offers a tonic for trouble times. Nick Bollinger tests the product.

Ry Cooder Photo: Joachim Cooder

The last time Ry Cooder released a new studio album was just before the U.S. election of 2012, when his fear that Republican Mitt Romney might win the Presidency prompted Election Special: the angriest, most agitated album of this lifelong humanist’s lengthy career.

So you might expect that after a year and a half of Trump he’d be preaching doom, damnation and didn’t I tell you so. Yet The Prodigal Son finds him in a meditative frame of mind.

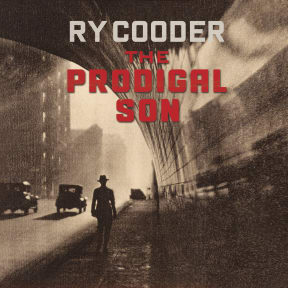

The Prodigal Son Photo: supplied

For someone known primarily as a guitarist, it’s his voice that is really the key to this album and delivers its central message. That’s not too different in essence from the one that’s run subtly and not-so-subtly through all of his work: solidarity with the poor, the dispossessed, the victims of inequality. But where on Election Special it translated into righteous rants, here it is expressed in the simple compassionate sentiments of old gospel songs.

On Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Everybody Ought To Treat A Stranger Right’ – with its modern resonances of migrants and refugees - Cooder is joined by the vocal trio of Bobby King, Arnold McCuller, and the recently deceased Terry Evans, the whole thing kicked along by the rattling rhythm of Cooder’s percussionist son Joachim.

Johnson has always been a touchstone for Cooder. His wordless hymn ‘Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground’ was a standout track on Cooder’s very first album, and later formed the basis of his monumental Paris, Texas soundtrack. And another Johnson tune here, ‘Nobody’s Fault But Mine’, takes him right back into the eeriest parts of Paris, Texas. With Joachim Cooder’s atmospheric loops and the King/Evans/McCuller trio lending their gentle gravitas, Cooder delivers one of the best vocals I’ve ever heard from him.

The spiritual mood doesn’t mean those songs don’t sometimes point a finger at the guilty. ‘You Must Unload’ – with its chiding lines about ‘money-loving Christians… trying to get to heaven on the cheapest kind of fare’ - was written by Blind Alfred Reed, a Tennessee fiddler and homespun preacher who recorded in the 1920s and who, again, has been a longstanding source for Cooder. He wrote ‘How Can A Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?’, another one from that very first album. Cooder’s ability to unearth an old and forgotten song that speaks to the modern malaise is one of his great skills.

But there are still times when the issue at hand is so specific that he has to write his own. With its references to Johnny Depp buying up buildings and ‘the Google-men’ who are coming downtown to drown in coffee, ‘Gentrification’ is really another version of the story he told on the Chavez Ravine album, of communities displaced by voracious capitalism.

That’s about as snarky as old Ry allows himself to get on this album. For the most part the emphasis is on empathy, on finding the things a divided people might have in common – which can make for some unexpected conversations, like the one he imagines between Woody Guthrie and Jesus Christ.

Cooder has titled the album after the Biblical parable about kindness and redemption, which is really what the whole thing is about - that and some of the best guitar playing you’re ever likely to hear, all of which adds up to an excellent tonic for troubled times.