To understand the history of our universe - and its future - we must understand that humans have only existed in it for a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of its history, one of the world's foremost theoretical physicists says.

Professor Brian Greene is head of Columbia University's Center for Theoretical Physics and is co-founder and chairman of the World Science Festival.

The author of six bestselling books, his most recent, Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe, explains the cosmos and our quest to find meaning in the face of this vast expanse.

Photo: supplied

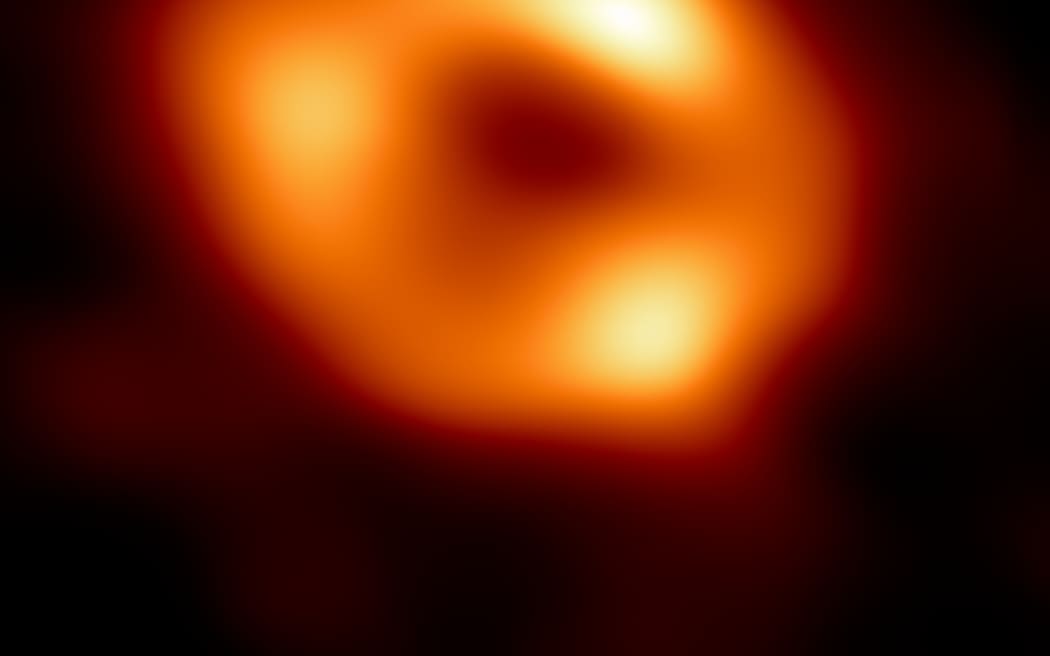

Even for someone immersed in the mysteries of the cosmos as he is, our first glance at a black hole recently was a big moment, he says.

“It was an amazing moment, absolutely, as a physicist I've been studying the mathematics behind black holes since I was a graduate student way back in the 1980s.

“And when we finally get to see these things, literally, through photographs taken by radio telescopes, the Event Horizon Telescope, it's just so thrilling to see the mathematics writ large across the night sky, where you actually see the edge of a black hole, you see the properties of black holes, aligning so spectacularly well with the mathematics that ultimately came to us from Albert Einstein.”

For many of us the vastness of the universe is impossible to grasp, but we must try, he says.

“If you really want to understand humankind's place in the cosmic order, you have to understand that cosmic order, or at least you have to take strides toward understanding it.

“Because when you recognise that we are not distinct from the universe, we are made from the very same material ingredients, we are governed by the very same mathematical laws that govern black holes, that govern planets, that govern stars, you recognise that there's a beautiful continuum between the fundamental laws, the fundamental ingredients and structures that we identify as ourselves, and thinking structures that we identify as gloppy grey brains inside of our heads that we use to identify who we are as individuals.”

We are nothing but highly organised collections of the various ingredients that make up everything else in the universe, he says.

“That shows a deep connection and also suggests strongly that to understand ourselves, we need to understand the basic structure of the cosmos.”

There is almost certainly life out there, he says, the more subtle question being is there intelligent life?

“On that I don't think we have any information at all. We don't really know what it takes for matter, not just to organise itself into a living structure, but to organise itself into a living structure that can think and can feel and can have a sense of self, and a curiosity about the universe that kind of organised matter - I don't know how likely or unlikely that may be.

“So maybe there's a lot of life out [there], but even if there is, how much intelligent life is out there in the sense of being able to communicate with us, that to me is the larger unknown. And I don't have any insight. I don't think anybody else does either.”

The universe is 13.8 billion years old, he says.

“If you focus on the universe that we have direct access to, because there might be others. But let's just keep the conversation simple. If you focus on this universe, it appears to have begun about 13.8 billion years ago, in this rapid swelling of space that we call the Big Bang.

“But the natural next question is what was before the Big Bang? What started the Big Bang? How did the material that ultimately gave rise to the expansion of space itself come to be? There's so many unknowns about the origin story of the cosmos that the best we can say is something really interesting happened 13.8 billion years ago.

“And that seems to be directly connected with the expansion of space that we currently observe, and the formation of structures like stars and galaxies that we can see dotting the night sky.”

Humanity’s part in the universe is miniscule, he says.

“If you take the history of the universe and you crush it into one year, on that scale we humans appear at 11:50pm a handful of minutes before midnight on December 31 of the calendar year.

“Imagine that the whole history of the universe squashed into a single calendar year, and we don't show up until the last handful of minutes. That's how small our footprint is on the cosmic timeline.”

Photo: supplied

Mathematically it is possible there are parallel universes, he says.

“When it comes to ideas of parallel universes I need to emphasise that this is a highly speculative idea. We do not know whether it's correct. But our mathematical theories do suggest that there may be other realms separate from our universe that should rightly be called universes of their own.

“And those other universes could have different properties. They could be inhabited by life forms, they could be full of particles that are following different laws relative to the laws that we are familiar with.

“And one way to think about it is you asked about the age of our universe and I spoke about 13.8 billion years, that's when we believe the Big Bang took place.

“Some of our mathematical theories strongly suggest that the Big Bang was not a one-time event. There are many big bangs, one of those big bangs gave rise to our realm that we inhabit.

“But the mathematics suggests that these other big things happening at far flung locations throughout the wider expanse of reality, those different big bangs would give rise to different universes.”

If that’s a mind-bending concept to grasp, he suggests thinking about it as a giant “cosmic bubble bath”.

“Our bubble is our universe, but there are other bubbles in the cosmic bubble bath, which would be other universes populating this landscape of reality.”

Humanity has never had more knowledge and yet the human condition drags us down, Prof Greene says.

“We have surmounted a great many challenges, if you look through the history of the species. And when you analyse and look at what's happening today, you can't help but say how could it be? How could it be that we're still fighting and killing each other?

“How can it be that we are still so selfish, that we're unable to see that there are things that we need to do for everybody, in order that all of us can survive and flourish and reach human potential?

“So yes, it is tragic, but at the same time, I have to say I am an optimist. I do think that overall, we will be able to surmount the challenges that we face, it will be painful, there will be catastrophes, there will be tragedies, unfortunately, we see them unfolding, at least here in America, now almost on a daily basis.

“So, it's utterly astounding what we do to ourselves. But I like to think that these are momentary blips, momentary challenges, momentary setbacks in the grand scheme of human progress, because there is so much on the positive side.”

The positive achievements of humanity give him hope, he says.

“Look at what we've done; we were able to manipulate matter, we've been able to travel to the moon, we're able to look into deep space, we've been able to unravel the fundamental laws that govern particles.

“I mean, this is an amazing achievement. And collectively, I can't help but think that we will be able to surmount the challenges that we face.”

When he looks up at the night sky, he still feels a great sense of wonder, he says.

“You see the deep richness of the heavens and all the resplendent glory, chock full of all the wonderful points of light out there.

“And you can't help but feel the very thing that we started our conversation with, you feel a connection to that cosmos, you feel like you are immersed within it, you are part of it.

“And that's a real feeling, because that actually is the human condition. We are not separate from the cosmos. We are part of it.”