Dr Sydney Savion is a behavioural scientist, who spent 20 years in the US military before forging a successful career as a corporate executive.

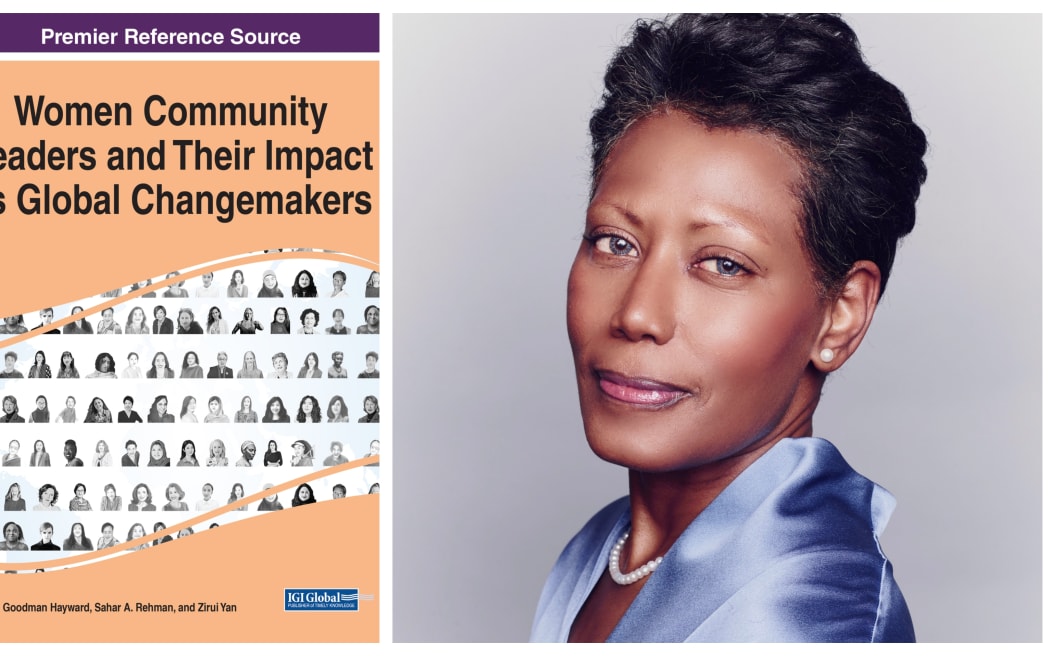

Sydney Savion Photo: Joe Pugliese

She helps organisations with staff training and development and has worked with companies like computer giant Dell, and more recently, she was the chief learning officer with Air New Zealand.

It was there that she developed a numeracy and literacy program for staff project Mana. Behind her career in the military, corporate and social enterprise arenas, there's been the mantra of striving for excellence, something drilled into her during her time in the military.

It took Savion 12 years to become an aerospace officer in the US Air Force, where she was responsible for the F-16 fleet, making sure everything was working safely and correctly.

Her last assignment in the military was at the Joint Forces Command and the training analysis and Simulation Center, where she used advanced technology to design develop and distribute learning globally and oversaw leadership development programs for more than 250,000 US military officers and the joint forces in her post military career she was working at in New Zealand when the pandemic hit.

She’s now back in the US working for a Google Ventures City Block Health, which aims to reduce inequalities and access to health care. It's been a very interesting career from the military through into corporate roles.

She tells Nine to Noon she has tried to use her applied behavioral science skills to help identify complex social problems and formulate solutions to solve those.

Savion describes her approach as holistic and describes behavioral science an “amalgamation of soft sciences” – sociology and psychology.

Her pursuit of excellence in corporate practice can be traced to her time in the US Air Force, where a high-pressure job with not a lot of room for error forged a steel now apparent in her current work.

“I was aircraft maintenance officer,” she says.

“I did multiple things, but primarily aircraft maintenance focused on F-16 fighter jet operations. I was responsible for ensuring that the fleet of fighter jets was operational at pretty much all times. And so that's what I did for a large majority of my career. And then also I did what they call operations in plant, responsible for helping plan operations, whether for peace or war time for not just the United States, but also for our NATO allies.”

She says what drove her to the military was a deep belief in mission, of giving herself to a cause, and a number of extended family members had a history in the military.

Her mother was tough and expected excellence, she says.

“She had a high expectation of me as the oldest to do more than I ever thought I was capable of. I don't think it's an accident, as Aristotle would say excellence is never an accident - It's always a result of high intention, sincere effort and intelligent execution.”

She wrote a booklet Camouflage to Pinstripes, about how difficult it is to transition from military life after being socialised to survive and thrive in an institutional environment.

“I spent the majority of my adult life in that contract, so to speak. And so everything from the discipline, whether it's how you wear your hair to what you wear, how you wear it, how you speak, how you address people, like every aspect, every facet of who you are, what you are, and how you do things is managed very rigorously, compared to the civilian society".

She left the military after finishing up her PhD at George Washington University. The hardest part of making the subsequent transition into the corporate world was how she treated time and the anxiety about standards.

“In the military, they train you to show up 15 minutes early. In fact, I got here probably about 30 minutes early for this conversation with you. My first job at Booz Allen Hamilton, I came in for work. My boss says, ‘hey, I need you to go attend this meeting’. And then I said, ‘Okay, sure. What time does it start?’ She's like, ‘No, it already started.’

“And I was like, ‘I don't know if I can go in, I will be late’. So I get down there to the meeting, and I'm standing at the door literally mortified to enter into this room, because I was late, even though it wasn't my fault I was late… I just couldn't bring myself to enter.

“In the military, that would be a form of disrespect, it would disrupt the flow and cadence of the meeting, and it just would not be tolerated. Whereas again, in corporate, a little less discipline around that.”

She was chief learning officer at Air New Zealand, a role that Jodie King and Christopher Luxon created.

She describes the project as democratising learning, allowing employees access to all the knowledge they needed to do their job. It lead to Project Mana.

“Part of the vision I set for the company was learning for anyone, anytime, anywhere, and that meant everyone in the company, from the cleaners, like I said to the people at the corporate headquarters on Fanshawe Street."

This project coincided with the Aotearoa Skills Pledge launched by Jacinda Ardern under the auspices of the Business Advisory Council, chaired by Christopher Luxon at the time.

"To help staff in organisations prepare for a rapidly changing future of work as a result of automation. So, it just all came together. I believe in providence, so that's how Project Mana was spawned.”

The company partnered with Literacy Aotearoa, a literacy nonprofit group to launch the initiative across the company.

“We identified those individuals that we thought needed the literacy and numeracy elevation the most. And so, while we did open it up to people who wanted to volunteer, we also had to identify people that we thought could benefit from this opportunity.”