Fifty-six years ago, Peter Jerram was nursing a hangover. It didn't help that he was on a boat in a massive storm, and that that boat was about to sink.

Jerram was on a trip with his university cricket team when the Wahine ferry was caught between ex-tropical cyclone Giselle and a southerly front.

At the entrance to Wellington Harbour the towering waves shoved the ship with 734 passengers and crew onto Barrett Reef as it struggled to reach shore somewhere else.

Fifty-one people lost their lives.

It had a big impact on Jerram and his teammates, all of whom survived, and for 25 years they chose not to speak of it. But a succession of reunions saw that change.

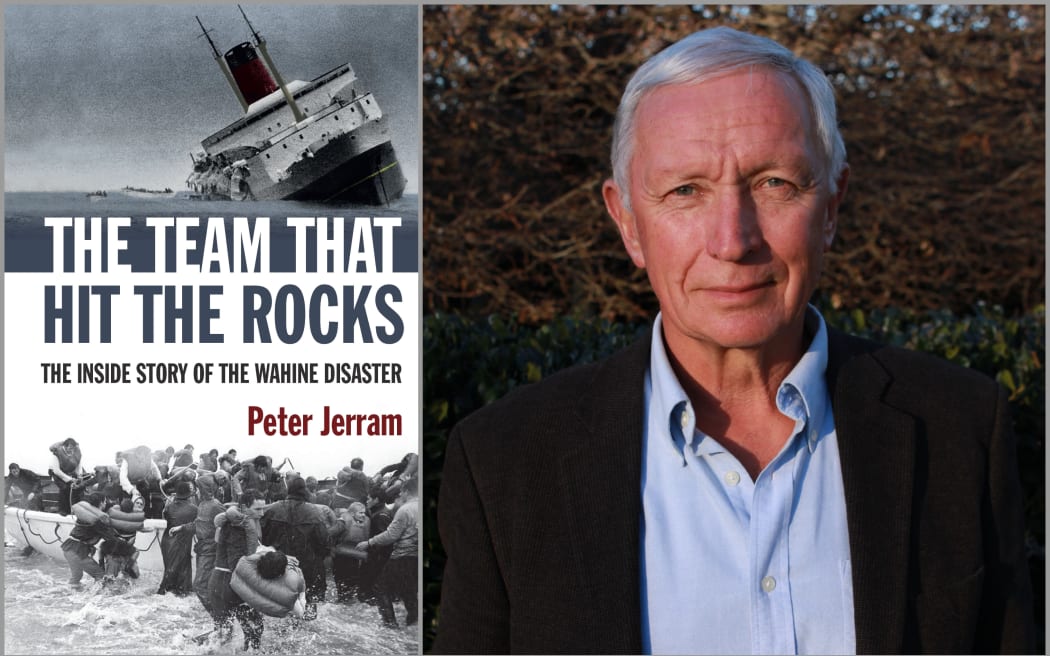

Photo: Supplied: Bateman Books

Jerram has gathered his team-mate's memories of that day and complied them into a new book The Team that Hit the Rocks: The Inside Story of the Wahine Disaster.

Jerram was deep in the bowels of the Wahine on his bunk when he realised something was very seriously wrong, he tells Nine to Noon.

“I went down and lay on my bunk. And I hadn't been there long, and I felt the thing hit the rocks. And I bolted. I thought this is serious, this is real. And I bolted up three, four flights of stairs to get out to C deck where I managed to push the doors open.

“And what I saw shook me very badly. The sea was unbelievable, I called it a maelstrom. And it was just a white foaming, unbelievably dangerous looking sea.”

It was a scene of chaos and confusion, he says.

“Bells were ringing, and they told us all to go to our cabins and get our life jackets, but we couldn't get to our cabins because they had immediately shut the watertight doors down there, our deck was already flooded.

“So, for two hours, we didn't have life jackets. We went to our muster stations and kept asking people where can we get a life jacket? No one knew.”

The day dragged on, he says.

“We kept getting these rather bland announcements, we’re perfectly safe, we're inside the harbour, we're drifting up the harbour.

“They had their anchors down and the ship actually scraped right across the reef taking more of the bottom out as she went.

“It nearly went ashore at Point Dorset. They thought it was going to, and if they had, then at that stage when the wind was at its most, probably no one would have survived.”

The Wahine reached its final resting place at 11.30am and started to tip over, Jerram says.

“The wind was still going pretty hard and around 12:30 it moderated a bit and the tide changed so the ship turned around 90 degrees.

“Some have blamed that for the ship tipping over, but in fact the vehicle deck down below, the great big empty space had filled with water, 3000 tons of extra water on the ship. We didn't know but she was sitting on the bottom.

“When she turned sideways, it created a lee on the starboard side, which in the end was where everyone got off.”

The first thing he saw when he got out on deck was people floating in the water.

“A lot of people had panicked at the first abandon ship call and had just jumped. And many of those people were unfortunately swept across to Eastbourne, where most of the deaths were.”

When the abandon ship announcement came panic set in, he says.

“We were caught completely unawares, we had no instructions, go to the starboard side it said, well, there was only one narrow door open on the starboard side.

“And I can only describe it as chaos. It was a very, very frightening moment. We all felt as though we're inside this thing that was going to turn over.

“We didn't know that the ship was actually sitting on the bottom. We thought it was in deep water, and it was going to disappear. You know, the classic story with the stern up and disappearing, and we'll all get sucked under.”

At that point, Jerram says, he “lost it”.

“I could feel my scalp crawl. And for a minute or two I lost it completely. I don't mind admitting it. I do, but then I'm old enough to not worry about it.

“I bolted and went up towards the port side, the high side, Because I could see that was a much clearer way to get out.

“On the way I found a teenage girl just sitting on the deck screaming. And it sort of brought me to my senses to some extent. And I said, 'come on, come with me. We'll get out of here'.”

When they got outside, he saw crew trying to launch life rafts.

“I helped this girl outside and that's when I first saw the people in the water. Seamen were launching life rafts, trying to launch them on the high side and push them against the wind, which was pointless.

“I saw a woman throw a baby into one of those life rafts. And I've wondered for the rest of my life whether they got her out, got the baby out.”

Eventually Jerram worked his way aft, after seeing hundreds trying to get into just four life boats, and jumped.

Survivors of the Wahine disaster are hauled ashore. Photo from archives Photo: New Zealand Herald

“I wasn't there for long, five or 10 minutes in the water, I just wanted to get away from that ship.”

In the following days and weeks it was a case of 'just get on with it', he says.

“We had a meeting two weeks after the disaster where we had a team photograph taken in Christchurch.

“And at that, our captain Kerry Armstrong said to us, 'you guys, you've all got work to do back in your studies, go home and put this behind you'. And that's it.”

A quarter of a century later, at a reunion, Jerram realised that burying the memories away wasn’t working.

"We had a game of cricket in Blenheim where I live. And that night, at a bit of a party at my house, one of the guys stood up, 10 o'clock at night, and said ‘I'm going to read the notes I made soon after’ and away he went.

"And I looked around the room. And there were a couple of guys with tears streaming down their face. I suddenly realised, holy moly I'm not the only one.”

He had been tormented for years, he says.

“I’ve been worried all the time, worried about my own behaviour inside the ship at the time of the evacuation. I'd always thought I didn't do well enough. I now don't feel that at all. Or perhaps I didn't do well enough, but it no longer worries me, writing the book’s helped that a bit.”

One of his teammates told him for several years after the events in 1968 he shook with fear.

“But counselling, there was no such thing, PTSD, we'd never heard of it.”

Jerram also delves into the cause of the disaster, which was exacerbated by errors made by the captain, he believes.

The captain reduced revs as they began to lose control and didn’t employ the anti-roll system that was on board. The court of inquiry however absolved any individuals of responsibility, he says.

“The three sea-going men [2 marine captains one marine engineer] all wrote a 14-page qualification at the end of the court of inquiry book disagreeing with the official findings.

“They thought that the Master had had done poorly in a lot of respects and that he should have been charged.

“The first of those respects was not using the flume tanks. The second they are all considered, he should have actually sped up and gone faster.”

There was little cross-examination at the inquiry, he says.

“I think it's a complete rewrite of the history actually. I think for 56 years people have been led to believe that the Wahine was sunk by a big storm.

“In fact, she was sunk, and particularly the lives were lost, because of poor decision-making by the guy in charge.”

The disaster, Jerram says, changed his life in various ways.

“Among other things it got me my wife, because I had this rather gorgeous-looking girl at Lincoln who I had my eyes on, but someone else had found her first.

“And when I got back, I found that she'd been very distressed about what was happening to me. So, we ended up getting married five years later, we had 46 years together until Ali died in 2016.

“The other thing is after 25 years, when we started to come together, and all of the subsequent reunions, we've formed, a band of brothers, and sisters actually, because the wives and partners had been a major part of it. And that's been a very big part of my recent life.”