Fourteen terabytes of underwater clicks, booms, songs and static are revealing what a noisy place Cook Strait is, and how important it is for many species of whales and dolphins.

Kim Goetz preparing a shallow water mooring containing underwater hydrophones for deployment in Cook Strait. Photo: Dave Allen / NIWA

In the middle of last year, NIWA marine mammal expert Dr Kim Goetz deployed seven acoustic receivers to record underwater sounds in Cook Strait.

She’s been back to download the first six months of audio and what she’s found has surprised even her.

Dr Goetz is interested in whales and dolphins, because even though nearly half of the world’s 80-or-so species have been recorded in New Zealand waters, we know we very little about them. Most of our information comes either from stranded whales, or from sightings at the surface – yet we know that cetaceans spend much of their time underwater.

Beaked whales are a particularly elusive group of whales, and rarely recorded, but Goetz says she definitely has many audio recordings of Cuvier's beaked whales. She was surprised to find they were being recorded throughout the time the hydrophones were in the water, and at all of the listening station sites, including the sheltered waters of Queen Charlotte Sound.

Although Goetz says there are very few recordings to compare with, she is pretty confident that she has also recorded strap-toothed beaked whales and Gray's beaked whale.

Recordings of humpback whales fitted previous observations made by the Cook Strait whale project, which has shown that Cook Strait is an important migration route for whales en route from their feeding grounds in Antarctica to their breeding grounds in the tropics. Humpback whales were common in June and July, but from August onwards - coinciding with the time the whales had moved north - there were no calls.

For some other whale species, Cook Strait appears to be more of a barrier than a migration path. Antarctic blue whales were only ever recorded at the eastern end of the strait, while a recently recognised group of New Zealand blue whales were only recorded in the west, on the Taranaki Coast.

More unusual visitors - Antarctic minke whales - were also heard on several occasions, the first time they’ve been recorded in New Zealand waters.

Dr Goetz has not yet analysed the many dolphin recordings, although a first look at the data makes it clear that dolphins – which are very abundant in Queen Charlotte Sound, where they are commonly seen by boaties – are very active at night. She suggests this is probably because they are hunting for squid which move up from deeper waters when it is dark.

She says she has also recorded sounds made by large groups of fish communicating with each other, known as fish chorusing. These sounds play an important role in the behaviour of fish species.

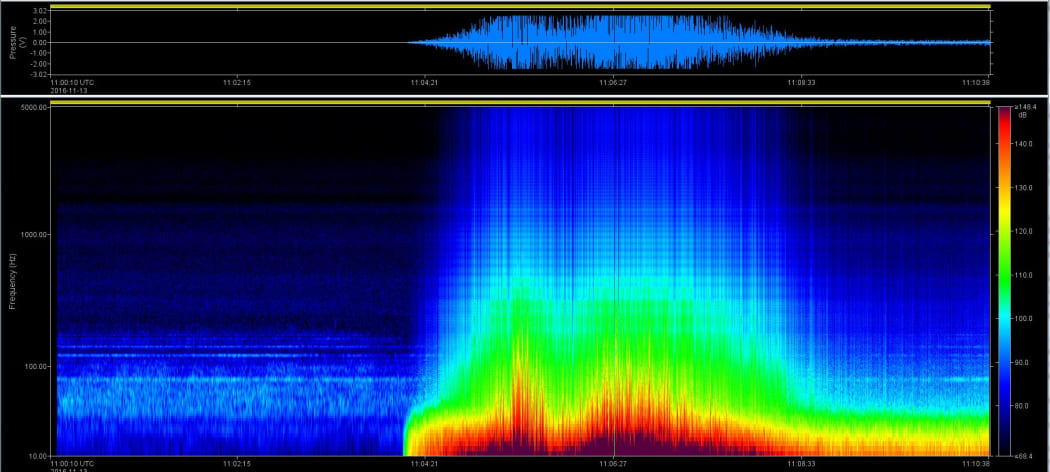

A sonograph of the Kaikōura earthquake in November 2016, as recorded on an acoustic listening station in Cook Strait. Photo: Kim Goetz / NIWA

A noisy place

Kim Goetz says that Cook Strait is a very noisy environment. A lot of general ambient noise comes from wind, waves and storms, while boat traffic is a significant noise generator.

The underwater hydrophones were also well positioned to record the sounds of the Kaikōura earthquake on 14 November 2016, along with its many aftershocks. However, Dr Goetz points out that the hydrophones are designed with marine mammals and not earthquakes in mind, so the enormous pressure and noise of the quakes overwhelmed the capacity of the recorders, producing just scratchy static, although they did make an impressive visual signature on sonographs of the audio.