It’s time for the Prime Minister’s Science Prizes!

Every year, five prizes are awarded to emerging and established researchers, science communicators and educators at the top of their game.

The winners of the 2022 Prime Minister's Science Prizes. From left to right: Doug Walker, Associate Professor Dianne Sika-Paotonu, Benjy Smith, Professor Valery Feigin, Associate Professor Jonathan Tonkin. Photo: Supplied / Prime Minister's Science Prizes

Follow Our Changing World on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeartRADIO, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts

The main prize, Te Puiaki Pūtaiao Matua a Te Pirimia, was awarded to the multidisciplinary National Institute for Stroke and Applied Neurosciences at Auckland University of Technology.

Led by Professor Valery Feigin, the team has done extensive investigations into stroke incidences and burden worldwide.

The National Institute for Stroke and Applied Neurosciences have won the 2022 Prime Minister's Science Prize. Photo: Matt Crawford

Now they are focused on developing the most cost effective, widely applicable strategies to reduce stroke incidences, including a free mobile app called Stroke Riskometer aimed at helping people lower their individual stroke risk.

Congratulations also to Associate Professor Dianne Sika-Paotonu, who won Te Puiaki Whakapā Pūtaiao – The Prime Minister's Science Communication Prize. Based at the University of Otago, Wellington, Dianne is an immunologist and biomedical scientist. The focus of her mahi is on addressing health inequities that exist for Pacific and Māori communities, through research that is grounded in respectful and inclusive engagement with these communities.

She was a key science communicator during the Covid-19 pandemic, and a strong proponent for Pacific and Māori researchers and health professionals to be given the opportunity to lead and make decisions for their communities.

Associate Professor Dianne Sika-Paotonu has won the 2022 Prime Minister's Science Communication Prize. Photo: Supplied / Prime Minister's Science Prizes

On this week’s Our Changing World we meet the other three prize-winners and learn a bit more about their award-winning mahi.

Te Puiaki Kaipūtaiao Maea / The Prime Minister’s MacDiarmid Emerging Scientist Prize – Associate Professor Jonathan Tonkin

Dr Jonathan Tonkin began his research career sloshing through rivers in Tongariro National Park when he studied benthic invertebrates for his PhD. Today he has mostly hung up his waders.

Now, from his office in the School of Biological Sciences at Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha, the University of Canterbury, Jonathan has a new key role: mentoring the large number of students and scientists that form his research group. Their research focus is on creating models to forecast how different communities of organisms will respond to environmental threats.

Science is very much a team sport in Jonathan’s large research group, and the diversity of what they’re investigating is head spinning. Master's student Rory Lennox is interested in interactions between trout and non-migratory galaxiids. Photo: Supplied / Prime Minister's Science Prizes

While the group is pursuing a wide diversity of systems and questions – like ‘what are the biggest impactors of crop yield loss?’, ‘how will Antarctic moss distribution shift under changing climate conditions?’, and ‘how will host-parasite evolution be altered by increased environmental stressors?’ – a strong focus on investigating river systems remains.

For example, modelling how different communities of species will be impacted under different rates of water flow through a river. One way to do this is to correlate the historical data on river flow – times of flood and drought – with data about fish species present. Then, you can use this model to input possible future river flow scenarios and ask what will happen to the fish in a different future, based on what we have seen in the past.

A second way is to create a mechanistic model, and this is what Jonathan and his team are aiming for.

Dr Hao Ran Lai is a postdoc modeller in the Tonkin lab, modelling the ecology and evolution of pests, pathogens and weeds. Photo: Claire Concannon / RNZ

They are creating models that hold key information about the natural history of different organisms in a system. For a fish this might be how many eggs it produces, what the survival and dispersal rates for different larval stages are, and the ability of adults to travel upstream during their life cycle. This type of model, Jonathan says, might be able to better forecast what will happen in our unprecedented future climate conditions.

Listen to the episode to learn more about this new way of developing models, and to hear about some of the other work going on in Jonathan’s lab.

Te Puiaki Kaiwhakaako Pūtaiao / The Prime Minister’s Science Teacher Prize – Doug Walker

Hands-on experiments, exciting demonstrations and getting students involved in making predictions are the cornerstones of Doug Walker’s science teaching philosophy.

Doug Walker, head of science at St Patrick's College in Wellington, in action in the classroom. Photo: Supplied / Prime Minister's Science Prizes

For the past 11 years Doug has been the head of science at St Patrick’s College, Kilbirnie, and the school has seen an increase in the percentage of students taking science across that time.

This was helped in no small part by Doug leading the development of a new general science course as an option for students in Year 12, as well as collaborating with other organisations such as Wellington Zoo, Te Papa and NIWA to bring science out of the classroom and into real life.

Doug Walker originally trained as a biology teacher, but has since extended his expertise into physics too. Photo: Supplied / Prime Minister's Science Prizes

But through online NCEA webinars and YouTube science demonstration videos he has also reached many more students and teachers both regionally and nationally.

The prize comes with $150,000 and Doug is hoping to use it to enable St Patrick’s teachers to travel to learn from other kura, and to support students that might be lacking financial means to get involved in science trips or competitions.

Listen in to hear more about what Doug’s classroom is like, and how he never misses an opportunity to share his love of science.

Te Puiaki Kaipūtaiao Ānamata / The Prime Minister’s Future Scientist Prize – Benjy Smith

As a student at Onslow College, preparing to represent New Zealand in the International Young Physicists’ Tournament, Benjy Smith came across an interesting discrepancy.

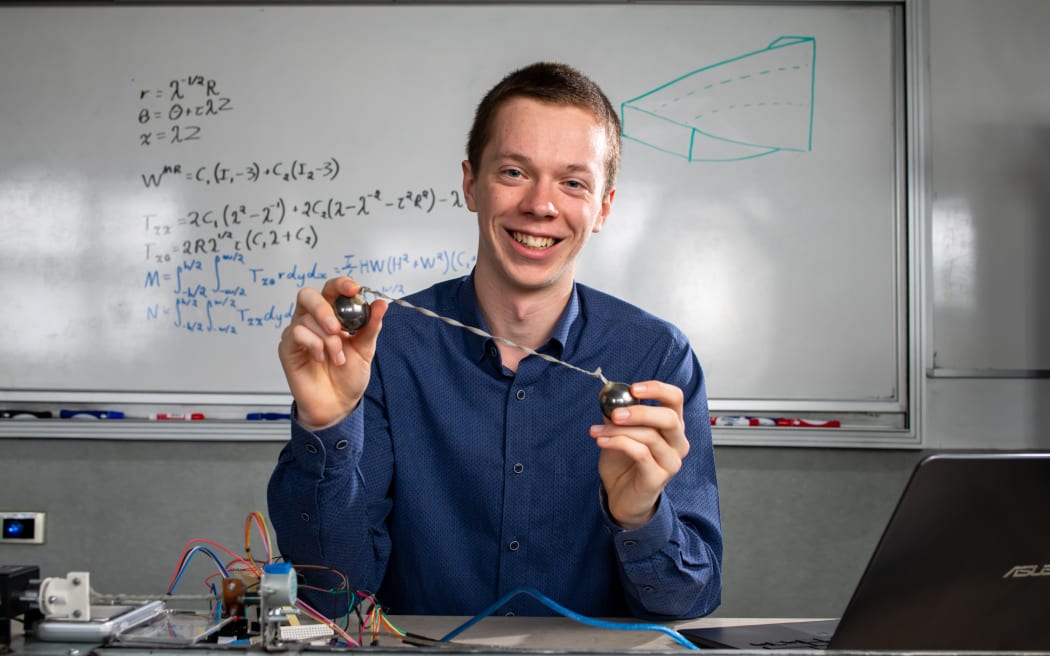

Benjy Smith was inspired to research the way materials bend and twist after encountering a problem at the International Young Physicists' Tournament. Photo: Supplied / Prime Minister's Science Prizes

The problem he was researching for the tournament was ‘balls on an elastic band’. He was asked to explain the phenomenon that happens when you twist the elastic band and then put the balls on table. When you do this the balls will begin to spin in one direction, then in the other.

But when he started exploring this, Benjy noticed that when he twisted the elastic band it would first make nice helical shapes, but then distort into other more contorted arrangements, and none of the models he found took these into account.

To investigate, he set up a system to twist an elastic band. If the distortion could be predicted, future models could incorporate it.

Now Benjy is a first-year student doing a double major in physics and computer science at Te Herenga Waka, Victoria University of Wellington. Claire caught up with him on campus to find out more.

To learn more:

- Valery spoke to Morning Report about the big win for the National Institute for Stroke and Applied Neurosciences

- Lean more about Dianne in this article, and hear Dianne speak about her research and science communication efforts on Nine to Noon.

- Valery also spoke to Nine to Noon last year about health apps for stroke prevention.

- Listen to last year's episode about the 2021 winners of the Prime Minister's Science Prizes.