A newly unveiled fossil fish called Qikiqtania wakei is thought to have shunned the forward march of evolution, eschewing the ability to walk and deciding to stay in the water.

A close relative of the four-legged fishapod Tiktaalik, the Qikiqtania has been encased in rock waiting to be discovered.

Both were found in rocks about 375 million years old during a 2004 expedition to the Canadian Arctic by paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Dr Neil Shubin and his team at the University of Chicago.

“It was a bit of a quest to find it (the Tiktaalik) because it’s up in the Canadian Arctic, it’s in rock, it’s not in ice and you know, the fossils are relatively small and the Candian Arctic is very big,” Dr Shubin told Kim Hill.

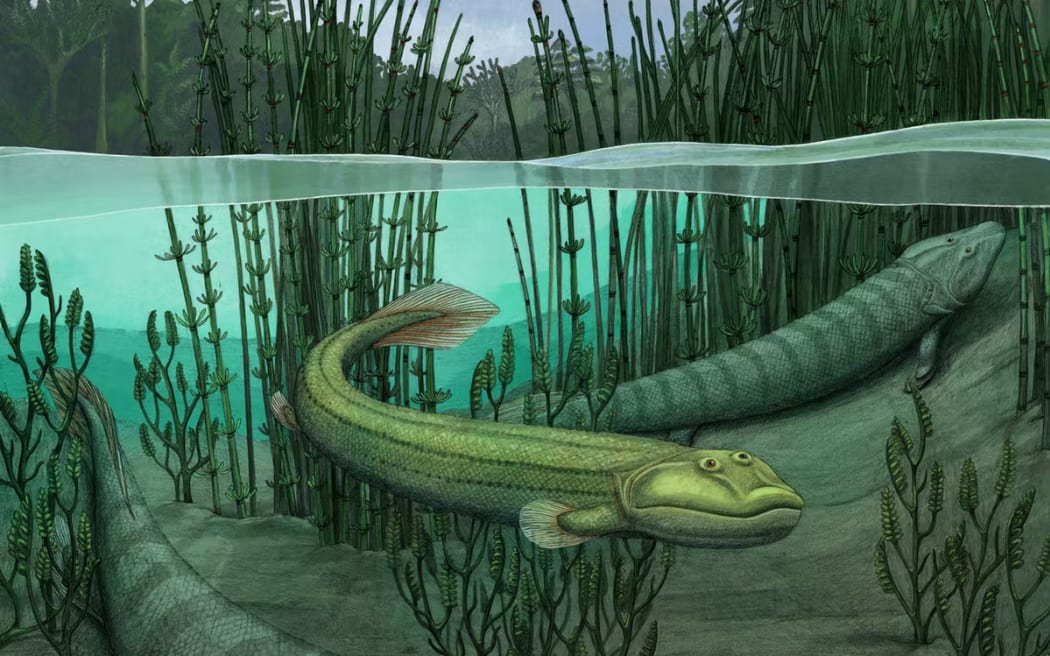

Qikiqtania wakei (front) was more suited to swimming than its larger cousin Tiktaalik (back) Photo: Alex Boersma

The Tiktaalik has been widely celebrated as the fossil link between fish and land animals.

“Tiktaalik, if I was to hold it in front of you, what you would see is an animal about a metre and a half long. It looks like a fish in some ways, it has scales on its back, and it has fins with fin webbing.”

If you were a fish specialist, you might even notice fish-like things about its shoulders and head, he says.

“But then you’d see the head – it's like a flat head with eyes on top, much like a land-living animal, an early tetrapod. It has a neck – no fish has a neck.

“When we looked inside the fin, what we saw was inside that fin webbing we saw bones that correspond to upper arm, forearm, even parts of a wrist.”

Tiktaalik had both lungs and gills, and had arm bones inside a fin.

“This was an animal that could support its body with its appendage, its limbs, but since it had fin webbing it could also swim, it had a neck so that when it was walking on the water bottom or on the mud flats it could move its head around.”

It was an amphibious creature which could live on both water and land.

“When you think about these transitions, these creatures aren’t invented out of whole cloth, they’re part of an evolutionary sequence,” Dr Shubin says.

Tiktaalik can be compared to other creatures in the evolutionary tree that are more fish-like or to more land-living animals.

Why would a creature like Tiktaalik want to get out of the water?

“To take a time machine back 375 million years ago, it helps to compare what water and land looked like at that time.

“The creatures in the waters, and these were freshwater streams, in these ancient rocks, were all carnivorous fish. They all had big robust teeth, shaped like steak knives, so water was filled with creatures that could eat you but were also competitors.”

Photo: Supplied

While the water was full of competitors and predators, the land at that time had neither of those things.

“Think about it as a world of opportunity and a world of getting away from a harsh landscape so any feature that these creatures would evolve to get them into the shallows, get them into the mudflaps would get them away from fish predator and competitor landscape.”

The Tiktaalik’s upper arm bone has crests for muscles to attach to, “very powerful ones that likely supported the limb as the animal walked about. Likewise, it had an elbow that suggested the creature could flex it like when you do a pushup”.

Qikiqtania has a head very much like Tiktaalik, the shapes of its bones and the way they fit together are largely the same.

“The difference came in the fin, and it was a true surprise to us, something we only discovered before our entire laboratory was locked down three days before the Coronavirus pandemic lockdowns at the University of Chicago in March 2020.

“We put a block into the scanner and found an entire fin inside, I thought ‘oh my goodness’.

“Here’s where it gets interesting, it has the bones in a pattern like Tiktaalik, they’re evolutionary cousins yet, when we look at the upper arm bone, the humorous, it had none of those crests that I was telling you about to suggest there were big muscles.”

Instead, it had a paddle - a fin that couldn’t support its body’s weight. “It’s like a Tiktaalik with a swimming appendage”.

The researchers struggled to work out whether Qikiqtania was just an early version of Tiktaalik.

When Qikiqtania was analyzed in the evolutionary tree, it was discovered to be very advanced, Dr Shubin says.

"We know its ancestors had started to leave the water...it’s not primitively aquatic, it’s secondarily so...it went back into the water after its ancestors left the water.”

That set up new questions for the researchers – why would a creature do that?

Dr Shubin’s team speculates that water became a new resource for creatures like Qikiqtania. Its skull enabled it to feed in new ways - it could both bite and suction feed.

“Basically, what Qikiqtania is, is a creature that said land looks great but nope, I’m going back in the water.”

The boundary between water and land is porous, with animals going both ways, he says.

“This sort of confirms something, Darwin’s original idea of evolution to be quite honest, it’s not a unidirectional path but continual marker progress where one creature leads to the next improved version, it’s a tree of life following every direction.

“They’re opportunists, following every opportunity that opens up.”

Next summer the researchers will be going back up to the Canadian Arctic.

“I’m always on the hunt for new stuff so if the plan holds, we’re going to go to new areas and see what we can see – that's the joy of being a scientist, it’s always a process of discovery.”