Finding ground somewhere between memoir and history book, Fintan O’Toole documents the spectacular changes that have occurred in Ireland over the past six decades in his latest book We Don't Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Ireland Since 1958.

Born in 1958 to a working-class family in Dublin, O’Toole entered the world at a time of dramatic change for Ireland.

That was the year when Secretary of the Department of Finance T. K. Whitaker published his seminal study Economic Development, which set the course for the modernisation of Ireland’s economy and gave new hope to a country from which young people were fleeing.

The title of his book is a pun on a common idiom in Ireland, but also about the nation’s capacity for known unknowing, he tells Kim Hill.

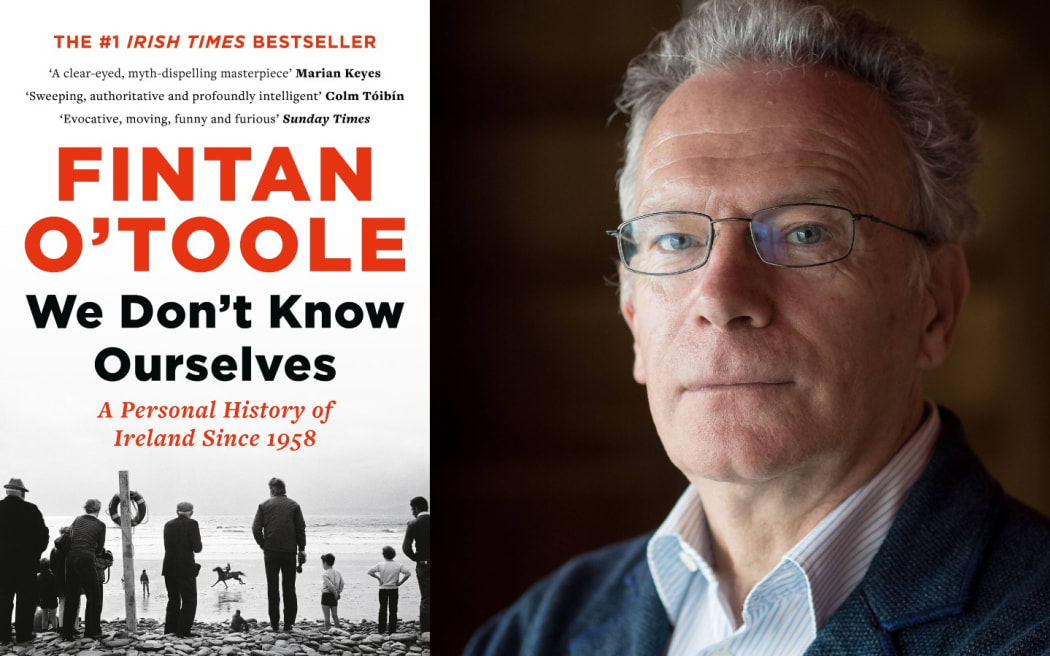

Photo: Supplied / Benson Russell

“There is, I think, this very interesting story about a place that chooses not to know a lot of what's going on within the society and develops a kind of talent really for being deliberately unaware of things that are often staring it in the face.”

Much of this is linked, he says, to Ireland’s history of mass migration.

“Irish people emigrated in huge numbers, and that mass migration does a funny thing to people, it means that you live in two worlds at the same time.

“When I was growing up, most of my father's brothers and sisters lived in England and they were both us and not us.”

A tolerance for keeping things out of the mind developed to assuage the pain that this mass migration wreaked on families, he says.

“Can you imagine what it must have been like for parents raising their children, knowing that they were raising them for export? And for a long, long time, before modern air travel, raising them in the sense that they might leave them at 20 and never see them again.

“So, the habit of mind really, of not knowing or not wanting to know too much about what was going on, I think was very deeply embedded in the society.”

Ireland came to develop an identity based on the fusing of religion and nation, he says.

“Ireland was very, very unusual in Europe. In almost all of Europe the settlements that came out of the horrible religious wars, was whatever the religion of the ruler is, that's going to be the religion of the people, whether you like it or not. And the Irish didn't like it.

“There's this kind of heroism in the way, the majority of Irish people decided, no, we're not changing our religion, just because the English monarchy tells us.”

Catholicism thus became a marker of national identity, O’Toole says.

“The state I was born into was 94 percent Catholic, 94 percent practicing Catholic, not people who just write down on the Census form - 'Catholic'.

“I mean people who were really very deeply believing, very conformist, did what the church told them to do.”

Only two countries lost population at the 1950s; East Germany and Ireland, he says.

“People were leaving, young people just left in droves. They couldn't take it and they couldn't find a life that they felt was adequate.

“And the compensation for this was to say, yes this is happening, but we are exceptional.

"We're the most Catholic country in the world, and it's a way of holding on to some kind of pride, some kind of identity. In the midst of this huge crisis, this demographic crisis.”

By the time O’Toole was born in 1958, the population of Ireland had halved since 1840 and there was a real sense that the country may cease to exist, he says.

Something had to be done, and in 1958 a young civil servant T.K. Whittaker, produced a document with the unassuming title Economic Development.

“This extraordinary man, and very admirable man, T.K. Whitaker, who was a brilliant, young civil servant, published this document, with the very deliberately dull title Economic Development, but it was a very frank document, basically saying this can't go on.”

Ireland desperately needed investment, Whitaker argued.

“He basically said we need capital, we need people to invest in the place, we need people to create jobs, to set up factories, and there's not enough capital in Ireland to do this.

“So, we've got to incentivise foreign companies to come in and do it. And initially, this was British, German, French, Belgian, whatever.

“But over time, this became American. So, the story I'm telling in a lot of ways is a story about Americanisation, it's a story about what happens when, what was still in a lot of ways a very traditional sort of culture, starts, without fully understanding what it's doing, on this process of becoming the major hub for American investments in Western Europe.”

That economic transformation started a very gradual cultural change in Ireland, he says.

“People like Whitaker, and the other people who supported him, said okay we've got to make these changes.

“They made a kind of a bet, which was you could change the economy, you could change people from living in the countryside to living in the cities, you could change the way the society works. But it would still be wholly Catholic Ireland.”

For a long time that bet paid off, he says.

“Sociology and economics and everything else would tell us 'no you can't do that, you can’t change the whole way in which the economy works and the way in which people work, the way in which they're educated, the kinds of jobs they're doing, you can’t change all of that and still have the same kind of basic ideological structure'.

“The cult is not going to survive this radical change in the world around it. But really up to the end of the 20th century, the bet seems to be paying off.

“The church is still really an extraordinary power in the land. And that sort of conservative nationalist Catholicism is still in many ways, the governing ideology.”

What’s dramatic about the story is when things do change, just how quickly that happens, he says.

“And it goes really within 10 years, and this is extraordinary I think in history generally, not just in Irish history, you think about an institution, which I suppose the Catholic Church was founded in Ireland around the fifth century AD.

“You've got 1500 years of this power structure and it disappears, it collapses within 10 years.”

Irish president Eamon de Valera kissing the ring of the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, 1962 Photo: University College Dublin

That could only happen if there was something fundamentally rotten at the heart of the nation, he says.

“Nothing that's as powerful as the Catholic Church is going to collapse so quickly, unless there was something else going on, unless actually, this doubleness, this knowing not knowing thing, meant that actually a lot of Irish people were kind of already living two lives, they were, I think amphibious.

“They were living in sort of modernity of sex and drugs, and rock 'n' roll, while in many ways — for quite a long time — actually pretending to be still wholly Catholic Ireland, and eventually this town isn't big enough for both of them. One of them has to go. And in the end actually economics and the changes that economics bring about, turned out to be more powerful than the cult.”

The country now has a kind of post-identity identity, O’Toole says.

“We had an identity which was so overwhelming and so suffocating in a way, that just being free of it is itself a source of national energy.

“If you talk to younger people, and say what's exceptional about Ireland, what's fantastic, they'd probably say, well, Ireland became the first country in the world to introduce same-sex marriage by popular votes, as it did in 2015.

“It was unimaginable, even 10 years before that. So, the Irish people undoing so much of that construct of this very conservative Catholicism. That is an energy in itself.”

Ireland has seen the danger that lies in toxic nationalism, he believes.

“We had a horrible, horrible experience of theocracy.

“And we had a horrible, horrible experience of where certain kinds of exclusive tribal nationalism can lead you. So, we have this terrible 30 year conflict in Northern Ireland of two competing nationalisms.

“I think, out of that, these bad examples, we've learned something about pluralism. And we've learned that actually, you can have a very pluralistic identity, without losing your sense of belonging, or your sense of self.”

Ireland is one of the very few countries in Europe that does not have a have a right-wing, nationalist anti- immigrant party, he says.

“And it doesn't exist because we know that simplistic us and them politics leads you into a very dark place.”

Fintan O’Toole has worked as a columnist for The Irish Times since 1988.