A psychoanalyst who has written a book on the history of mind control says we must remain constantly vigilant against corporate and government manipulation.

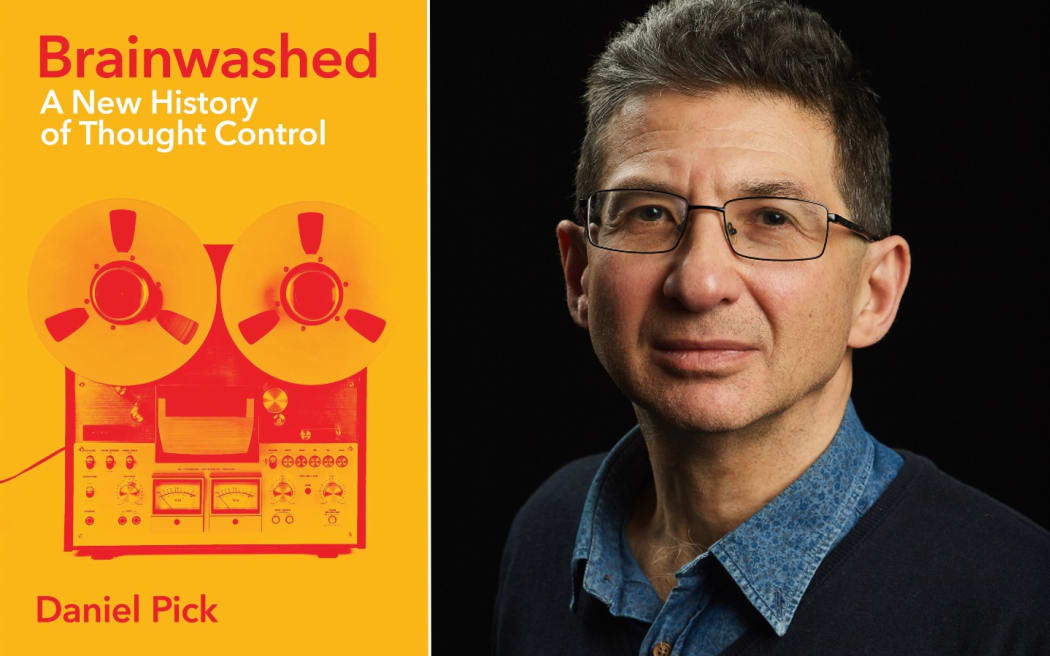

Photo: Supplied

Daniel Pick explores the intriguing world of mind-control in his book Brainwashed: A New History of Thought Control.

The book traces thought control techniques over several decades, from the beginning of the Cold War after 1945 to the present day, seeing cultural oddities like the QAnon conspiracies as examples of how some have become neurotically paranoid of social control by the powerful in society.

A professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, Pick is also a fellow of the British Psychoanalytical Society. He tells Saturday Morning our human nature makes us vulnerable to propaganda and groupthink, particularly during times of war and crisis.

Pick says the drive towards group psychology and ‘brainwashing’ populations began during denazification after World War II, when the great powers began re-establishing zones of influence.

The origins of the term brainwashing are disputed, Pick says.

“It was popularised, if not invented, by an American journalist who had been in the Office of Strategic Services, the US intelligence agency during the war, Edward Hunter. He had links to the CIA after the war.

“He wrote an article in 1950, in the Miami News, about this new phenomenon he called brainwashing… In The Guardian newspaper in Britain an article was also written in 1950.

"So, it appears on both sides of the Atlantic and what these journalists were concerned about was what was going on in Maoist China, the newly created People's Republic and these techniques of so-called thought reform, or thought control, that were emerging in that period.

“Hunter writes this article warning about new methods that he thought were bringing together the ideology of communism, with a new set of techniques from psychology to influence people in coercive ways to believe new things.”

That concern was amplified in 1953 after the UN brokered a peace deal ending the Korean War, with the country partitioned. A number of American GI prisoners refused to be repatriated back to the States and instead opted to live in Mao’s China. The furore that followed helped inspire the movie The Manchurian Candidate.

“This sets off in America a huge debate about how was it possible that American soldiers could freely choose to live in China and that's where this label brainwashing comes of age really - there's a storm of controversy, suggesting they must have been brainwashed during their captivity,” he says.

During that same year Polish writer Czesław Miłosz draws attention to the fact that Europe also had its own form of mind control, in his celebrated book The Captive Mind. It is an insider’s view, giving a richer, more layered picture of life under totalitarianism and thought control.

“It’s an account of life in Stalinist Poland,” Pick says.

“He's kind of avant garde poet and intellectual with misgivings about what's happening, so he defects and then writes this celebrated book in which he's saying, ‘You need to sort of drill down under the surface that these labels won't do'. Even the sort of Orwellian 1984 image of brainwashing and total subservience - this sort of terrifying story that Orwell tells is only one way to think about what it was like under totalitarianism.

“He wants to say there were many different ways that people responded in his society to living under communism - you can't have a sort of blanket explanation.

“Some people were smitten by communism, or as he puts it, took this imaginary drug - he calls it the Murti-Bing pill. They swallow this pill where they become total converts to communism.

“But others have much more ambiguous attitudes - they negotiate, accommodate and compromise. And often he describes people who keep their private thoughts intact, very secret, and go through a kind of paying lip service to communism to sort of, in a way, accepting the regime because they have no choice, but where their public actions and performances are disjoined from their inner worlds.

“Everyone kind of lives in this theatre of politics where they appear to be compliant, but really harbouring their own secret doubts. And he thinks that this creates a society where people are constantly second guessing what other people believe, because you cannot take statements at face value, but you wouldn't call people out because it's too dangerous.”

Brainwashing implies inculcating people with new ideas and new ways of thinking. Pick believes this is highly doable when people are put through trauma.

“Our hold on sanity and reason and thinking is fragile and precarious at the best of times. We all know that we can be driven into crazy states, people get into states of road rage, just driving down the road, where they lose their balance and equilibrium.

“If you put people in terrifying conditions, if you torture people physically or mentally if you give them no access to other information, and so on, damage is done. We're all you know, people are resilient to varying degrees in, in these situations. And of course, you can have whole communities that are held captive.”

During the Cold War period, there were various kinds of experiments involving sensory deprivation or overload, with noise, with silence, with terror, with drugs, with playing on people's guilt and shame, and forcing people into humiliating situations.

Pick’s book revisits classic literature that emerged in that period on the subject.

He points to other books exploring brainwashing, including like Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, by psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton.

"I think his argument, which would also be mine, is that we need to be sceptical about the way in which brainwashing can be used in all sorts of ways, ideologically, or as a political football, or even in trivialising ways where any kind of influence or pressure is kind of just labelled ‘brainwashing’,” Pick says.

“But also hold on to the fact that actually you can do dramatic and terrible things to people in these kinds of conditions.

"That's what Lifton describes, and he tries to explore this in his account of the Korean War and of totalitarian brainwashing, as well as also casting a mirror on the West and the more sort of subtle ways in which we can be manipulated. Whether it's in cults or movements that take people into sort of closed systems where there's no way out, or just in more ordinary, everyday life, the ways in which we can also be pressured, influenced or nudged."

Pick says during the 1950s period there emerges a vocabulary trying to convey the spectrum of mind control, from these more extreme states where people feel absolutely trapped or disorientated or assaulted, to more ambiguous ways in which we go along with something.

There is an increasing awareness of advertising by corporates and cultural brainwashing and social coercion.

“It was one of the other great themes of this 1950s literature, with books like The Hidden Persuaders, where it's not clear that we're acting, as it were, entirely autonomously, but nor are we captives in chains - that something seems to happen where we sort of end up doing things or believing things or voting for things that maybe are at odds with other beliefs we hold.”

Vance Packard’s 1957 work The Hidden Persuaders anticipates the increasing power of surveillance, in its discussion of mind manipulation.

“He writes another book soon after called The Naked Society, very worried about the intrusions on privacy with technology in the early 1960s,” Pick says.

“He's very worried about how psychology and psychological professions have been exploited and mined for insights that can be used by Madison Avenue to serve the interests of corporate enterprises, capitalism, and so on, in which people think that they're freely choosing what they consume, but actually they're faced by a barrage of messages all the time - a kind of total deluge through radio, through television, through film, through billboards, through any number of magazines, in which we're coaxed and nudged to both to desire things, but also to be anxious about things that make us consume.”

Pick says his own book deals with the human condition, of interdependence and the psychological difficulties we face living within a political economy and during a particular point in history.

“I think it's interesting to study the conditions that are more or less conducive to brainwashing or groupthink,” he says.

“Groupthink is another term coined in 1952 by another American journalist, and he was very worried not about brainwashing, but a kind of gradual synchronisation that he thought was happening in American society and the American business world where people just were gradually groomed to all behave and think in rather similar ways.

“So I think that that we're talking here at the interface of what it is just to be a human being in which we are prone to be suggestible or influenced, but also the mechanisms and processes of institutions that may exacerbate that problem, or conversely, that can help people to resist that and even groups. Groups can sway us or make us do crazy things, you know, the kind of psychology of crowds.”

Pick also looks at forms of thinking that neurotically find a manipulative act or conspiracy by governments under every rock. These may be culturally prevalent now in the social media age, with QAnon and Covid-19 conspiracies the most recent examples, but this type of pathological thinking has been documented before.

“You can have more or less healthy suspicions about influence and that we need to be sceptical and vigilant about manipulation. But there can also be more psychotic forms of anxiety about conspiracies, or about people doing dreadful things to us.

‘One of Freud's early followers who I write about briefly in the book, [Viktor] Tausk, wrote a paper in 1919 called The Influencing Machine about schizophrenic patients who he observed in hospitals were often convinced that there was a machine outside of themselves, totally controlling their minds, and manipulating them.

“And in Tausk’s account of this, he describes patients who thought that the chief doctor in the hospital was at the heart of this conspiracy of this influencing machine sort of in a way governing their actions and their thoughts and even the movement of their limbs.

“Where do we draw these lines between a more healthy scepticism about the deep state or power or plots that of course can exist - that's not that plots don't exist - but there can also be more paranoid or crazed versions of those fears where sort of everything supposedly connects.”

Pick also looks at Ernest Dichter, a US psychologist and marketing expert known as the "father of motivational research." Dichter pioneered the application of Freudian psychoanalytic concepts and techniques to business in particular, to the study of consumer behaviour in the marketplace.

“His motivational research techniques to delve into people's unconscious desires and fears… Before there was Freud's nephew, Edward Bernays, who was one of the founding figures of American public relations a bit earlier on.

“But this idea that you could use these insights into the fact that people do have an unconscious mind that so much of our mental functioning is unbeknownst to ourselves.”

Bernays set the stage for modern day framework propaganda employed by governments, with many now employed to sway public opinion in democratic societies, something that has grave implications for the notion of human freedom. It can be used to avoid effectively tackling existential threats to our existence, like climate change.

“There are many other contexts too in which one needs to rethink not just about brainwashing, but about the kind of politics that encourages people to face certain realities, for example, climate change, as opposed to denying it or, you know, turning a blind eye to the catastrophe that's happening,” Pick says.