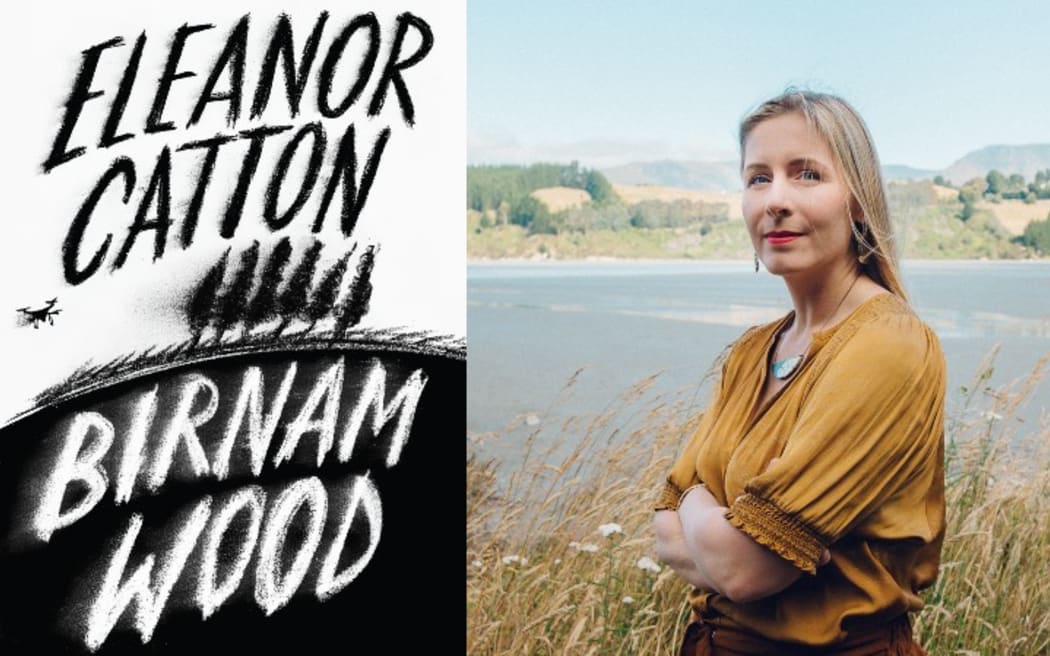

Photo: supplied

It's been a decade since New Zealand author Eleanor Catton's novel The Luminaries won the Man Booker Prize, making then 28-year-old Catton the youngest author ever to win the award.

Her almost instant international literary fame came at a personal cost in 2015, with Catton copping attacks from then-Prime Minister Sir John Key and right-wing broadcaster Sean Plunket who called her an "ungrateful hua" and a "traitor" after she criticised Key's government during a literary event in India.

This week she released her hotly anticipated third novel Birnam Wood, a psychological thriller set in the South Island, with an ecological battle between good and evil at its heart.

It also features “self-important outrage-monger” New Zealand media personalities, an American tech billionaire and green activists who collide in a series of twists and turns that feels very of the current moment.

Catton told Saturday Morning’s Kim Hill that some elements of Birnam Wood were drawn from that time.

“In a funny kind of way, what happened in 2015 ended up giving me Birnam Wood,” she says.

“I did a lot of reading into political theory, economic theory,” and “out of all that reading came the first ideas for the novel”.

At the time, Plunket said “I don't see you as an ambassador for our country, I see you as a traitor."

“I’ve moved past it emotionally in all sorts of ways,” Catton says, but noted “one thing stands out as more sinister than the rest in my mind”.

“The right-wing group the Taxpayers Union published a list of all of the Creative New Zealand funding that I’d received over the course of my career up to that point, which amounted to about $50,000 over 10 years.”

The Taxpayer Union's press release was published by the New Zealand Herald among others.

"At the time this blatant attempt to intimidate me and kind of garner ill feeling towards me ... I just kind of can't believe now that something that sinister would happen with just no consequences," Catton says.

"I think back on that and I think what is arts funding really for, first of all?

"All of that funding was for services that I rendered and I did the job that I was paid to do."

Catton said that the idea that arts funding should "as a form of hush money" somehow "buy the artist's silence and complicity within every arm of the government ... is just absolutely absurd".

"It's such a narrow and blinkered and benighted way of looking at what the arts bring to a country.

"When I look back on it now I feel really angry that more people didn't see how incredibly sinister that was and come to the defence, not of me in particular, but just to the idea of what it means to have artists in the country who are adding all sorts of intangible values to that country's culture."

Catton agrees she was "disaffected" with New Zealand for a time as a result of the stoush and she didn't want to put too much bitterness into Birnam Wood, even though elements of it are satirical about Aotearoa life.

She also delved heavily into research and reading for the novel.

"Probably kind of two or three years of reading went into Birnam Wood before I even properly started to work from what is now the beginning of the book."

The thriller is a leaner, quicker-moving book than the hefty The Luminaries was.

"It was important to me to write a book that kind of drew the reader into the future in a positive way."

Catton upon winning the Man Booker Prize in 2015. Photo: AFP

One of the themes of Birnam Wood is the cost of the technology that surrounds our everyday lives.

"So much of our lives are mediated through these kind of incredibly destructive devices."

Catton left all social media a few years ago after the "ungrateful" controversy, "thankfully, for my mental health," she says.

"I am very, very suspicious of social media. I think that it is deeply distorting our humanity and is pushing us away from being moral creatures.

"I think that morality depends on presence and depends on the kind of communication that has to happen in time and in a room and in a community.

"There's something about the facelessness of online spaces that is incredibly corrosive, I think."

While she admits that many communities online, such as book groups, are positive, she says, "for me at least the price is too high".

"I found when I was on Twitter ... that it was starting to infect the way that I thought and kind of went about my day.

"There was this kind of internal advertiser that was always at work looking around at everything saying 'is this tweetable, is this tweetable?' and I just hated it, I just hated it.

"We can fool ourselves that (Twitter) is this form of kind of modern public square, but it's not that in the slightest. This is a for-profit space, this has been algorithmically designed to be addictive."

Catton insists that the world of social media is having a negative effect on human interaction.

"The algorithms are operating on us. In a sense ... they operate like psychopaths.

"An algorithm has an agenda, a for-profit agenda that it is hiding from you, very much like a psychopath does, and it is also manipulating you, it's flattering you into showing you things that it thinks you want to see. It's matching itself to a version of you that it wants you to like.

"This is incredibly psychopathic behaviour and I think that the world is becoming actually more psychopathic as we become more used to having our quote unquote social interactions mediated through algorithms."

Catton freely admits she's "very, very down on social media," but also worries about how we use our devices and how they are affecting us.

"We are all individually enriching these kind of tech overlords these people like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg and whoever else every time we give away for free data that is later monetised and then used to line the pockets of these people.

"They're more powerful than nations.

"They're incredibly, incredibly powerful people with moneyed interests all over the world. I feel very strongly that urgent reforms are needed.

"Going online is not an innocent act. It's an act I think of deep complicity."

Catton did say that she felt not all groups share equal responsibility for that complicity, but it is worth looking harder at the big picture.

"The people who are consuming more of the world's resources and are wasting more of the world's resources ought to be held to account," but she notes "the higher you get, the more powerful you get, the less responsible you are. It's the absolute opposite of the way it should be."

Based in Cambridge in the UK since 2017, Catton plans to return to New Zealand in May. Details on public engagements have yet to be announced.