The solidarity Ukrainians are showing each other in the wake of Russia's attack has made for a kinder society, says Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov.

''There is a feel of interdependence, there is a feel of respect for everybody who does something for others, for the frontline, for the soldiers. And everyone is trying to get involved in any kind of activities that are useful to the society," he tells Kim Hill.

Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov Photo: Andrey Kurkov

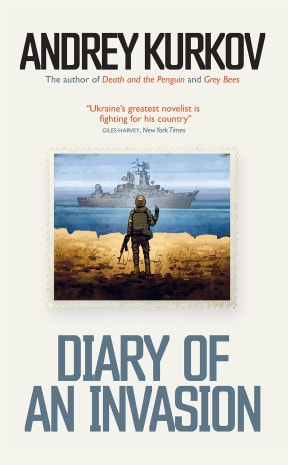

Photo: Welbeck Publishing Group

Andrey Kurkov is currently teaching post-soviet literature at Stanford University in California. His latest book Diary of an Invasion is a collection of his writings and broadcasts from Kyiv during the first months of the Russian invasion.

Kurkov, who spent last December back in Ukraine with his wife, says most of his friends have now returned to the capital city of Kyiv.

"The cultural life resumed in March, April [2022] with public events in the bomb shelters, rock concerts in the metro station underground, and since then a lot of things have happened."

Ukraine's anti-air raid systems are very effective, he says, destroying about 80 percent of the missiles and drones sent to bomb the Kyiv region - and city-dwellers have gotten used to them.

"Kyiv is full of life. Theatres are open and working. Cafes and restaurants are working. Museums are full of visitors. Public discussions are taking place not in the shelters anymore but in the normal way ... Of course, events are interrupted by the anti-air raid hearts but not every day and not always."

Before waking up to explosions outside his Kyiv apartment window on 24 February 2022, Kurkov didn't predict Russian leader Vladimir Putin would launch an "all-out attack" on Ukraine.

A year on, he is hopeful that the fighting in his country will end later this year but doesn't believe it will involve a "military victory".

More likely, Kurkov says, would be an end to hostilities and the beginning of negotiations actively guided by political leaders from other countries.

While the vast majority of Ukrainians say they're unwilling to negotiate with Russia over territory, many who are still in the country or taking refuge elsewhere are simply tired of the war, he says.

While NATO's attempt to gently prepare Russian leaders and people for the "failure" of their war is understandable, the approach isn't winning them any Ukrainian fans.

'[NATO leaders] want to slowly show Russians that they cannot win this war. It takes time, this policy, and it takes thousands of Ukrainian lives.

"The slow-motion delivery of weapons, when they were needed before, it does provoke some outcry in Ukraine ... Families are losing their husbands and sons. There are tens of thousands of new graves everywhere in Ukraine. This is all connected with the speed of delivery and quality of weapons."

For centuries, Russia dreamed of taking over the "very rich piece of agricultural land" that is Ukraine, Kurkov says.

Then in 1709, after Russian monarch Peter the Great overcame Ukrainian soldiers in the Battle of Poltava, they started regarding Ukrainians as traitors of the Russian empire, he says.

The subsequent "war" on the Ukrainian language and culture was accompanied by an attempt to make Ukranians as "collective and obedient" as Russians, Kurkov says.

Russia has created laws which make any form of protest impossible and at the same time has a "huge problem with morality" evidenced by Russian oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin and his "army of professional criminals" - the Wagner group.

"Putin allowed [Prigozhin] to release from Russian prisons tens of thousands of murderers, rapists and robbers in exchange for their participation in this war. And these criminals are promised to be sent home, pardoned as heroes if they survive six months on the frontlines."

Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin in July 2017 Photo: Sergei Ilnitsky / AP

Russian people have romanticised criminality for years, Kurkov says, but at heart, they are fatalistic and fearful.

Ukrainians, on the other hand, are individualists who value and feel deserving of freedom.

Until the 17th century, Ukraine occupied a huge territory – independent of the Russian empire – and made its own rules, Kurkov says.

Then in 1991, after the Soviet Union collapsed, Ukrainians went back to "their very individualist way of thinking and of behaving".

President Viktor Yanukovych's ousting in 2014 provided confirmation that the people of Ukraine could change the political system themselves.

As such, Vladimir Putin is "dreaming" when he argues Ukrainians and Russians are one people, Kurkov says.

"Several years before the [current] war he was saying Russians and Ukrainians are brotherly nations. Then he started saying that Russians and Ukrainians are one nation. And just at the beginning of the war, he announced that Ukrainians do not exist and were invented."

For over 300 "dramatic" years, Russia has tried to assimilate the people of Ukraine and punished their resistance, he says, so it's not surprising Ukrainians have been more focused on day-to-day life than surveilling their own history, Kurkov says.

Yet as the country shapes its future, he hopes people will reflect on the uniquely Ukrainian spirit of independence after World War I.

"It was a multicultural very pluralistic society with different leaders. Some of them were very good… and now forgotten. They should be dug out from the history and made into historical figures known to every Ukranian today."