Photo: Amanda Kvalsvig

February 25 is International Cochlear Implant Day and Wellington’s Dr. Amanda Kvalsvig joins us for a very special edition of "What I’m Listening To”.

Amanda had always been musical – singing, playing the piano and violin, and playing in orchestras, but at the age of 19 she first noticed she was losing her hearing.

In 2007 she received her first cochlear implant in Christchurch. At the time she had a toddler and a nine-month-old child.

Hearing music again was a transformative difference. She joins us to pick a track and explains why it’s special to her.

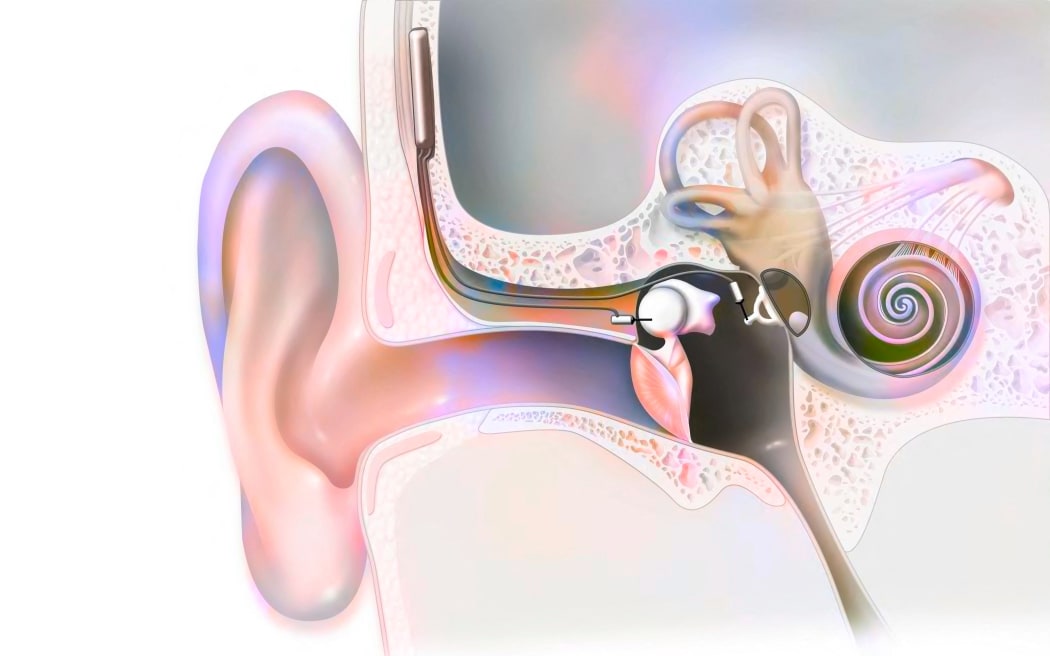

Photo: JACOPIN

TRANSCRIPTION

JIM

What I'm listening to now, on Sunday morning.

New Zealanders choose songs that inspire them.

Our guest today couldn't listen to any songs for a long time and even now she listens to them differently.

It is International Cochlear Implant Day today, the government funds cochlear implants, but the usual story - not enough to keep up with the demand.

Dr. Amanda Kvalsvig is an epidemiologist at the University of Otago in Wellington. She has two cochlear implants. Amanda, Kia ora

AMANDA

Kia ora

JIM

What are cochlear implants? What do they actually do? I think it's quite hard for the rest of us to comprehend what they do.

AMANDA

Oh, that's a really good question. Because I don't think even people who have cochlear implants always understand exactly how they work.

What do you have, is very, very clever technology. You've got an electrode that sits in your inner ear, and it's connected, right all the way up to your skin to a processor that sits outside, it sits on your ear, and the processor collects sound, and transmits it into the internal electrode. And that stimulates the nerve that sends sound to your brain and it tells your brain that it's hearing something.

So it's a completely electronic signal, which is different from the way we hear naturally. So I don't hear with my ears at all, I just hear through the electrodes.

JIM

So when you got the implants in the first place, you had to learn to hear differently.

AMANDA

Absolutely right.

So it doesn't give you your hearing back, it doesn't give you a natural hearing, it's a new way of hearing, and the soundscape that it gives you is different from the sound that you might remember before if you were hearing before, which I was.

So when it's first switched on is quite amazing experience, you hear a lot of sound, but you don't know to what you're listening to. It sounds very different. And that's the learning process that you have to do. It actually takes years.

And years on from the implantation, my hearing is still getting better because my brain is still learning to interpret what it's getting and perhaps that's the big lesson is you don't hear with your ears, you hear with your brain that your brain is doing the work in there.

JIM

It's amazing tech. You were 19 when you first noticed you were losing your hearing, and it got worse and worse and worse.

AMANDA

That's right. So through my 20s I lost more and more of my hearing until I could hear pretty much nothing.

JIM

And of course, you were already a doctor, you had to retrain.

AMANDA

That's right. Yes, I was doing clinical paediatrics, which I loved greatly, and had to stop that and find a new career and that was very hard to do.

It was very, very hard to step away from something that I loved so much, and actually was a big part of my identity - as I realized when I had to stop.

And I'm very, very fortunate because I found a second career that I also loved, and really enjoy, and that's being an infectious disease epidemiologist and working in public health.

JIM

Yes. But going back, I've heard you say that losing your hearing is just the start of the problem really.

AMANDA

Because, as I didn't realize at the time, hearing does all sorts of things. It connects us to the people around us. If you can't hear even the people closest to you, can't have a simple conversation with them. It is extraordinarily isolating.

JIM

Yes. And you were very social, I know. But then in rooms of people, obviously you found yourself completely alone. And that is why you talk about a loss of sense of identity, because your feeling of who you were inevitably changed.

AMANDA

That's right. It's as if you've been a certain person all your life and suddenly you can't be that person and you don't know who you are anymore. It is very disconcerting. It actually gets at the very basis of wellbeing.

JIM

In 2007, you received your first implant. I know you had a toddler and a baby who you couldn't hear. But do you remember how you felt when the implants started to work for the first time?

AMANDA

It was absolutely extraordinary. I don't almost have words to describe it. But they switched it on and I heard that they use a kind of pure-tone test signal. And I heard it so that was really the first thing that I heard, and I heard it as a major chord arpeggio, which was the first thing I'd really heard in in years.

But then we went outside and they were all kicking leaves for me and I could hear the rustling the leaves and that was fascinating - every little sound was fascinating.

And we got in the car. We were driving through, it was in Christchurch, and we were driving through the streets and I suddenly heard a ticking sound, it was the indicator. I had forgotten that indicators made a noise. And it just forgotten that, because hadn't heard it for so many years.

And so, every tiny thing was fascinating. And then hearing my children's voices, hearing my husband's voice, my mom's voice, that that was an incredibly moving experience.

JIM

And 10 years ago, after your second implant went in, I was reading you recognized a Beatles song, on the way home. Which one was that out of interest?

AMANDA

Oh, gosh, I can't even remember. It was - I think it was Rubber Soul that was playing. So it's one of those tracks I think. Um, but yes, we were in the car and I had taken my old processor off and I just had the new one on because I wanted to train myself to listen with it

And just going back a bit people said to me with that second one, they said, “Look, this ear hasn't heard anything, over 20 years, we don't know if it's going to work at all, we're just going to take (a chance), we think there's a chance and we're going to give you that chance, but please keep your expectations really low.” And I did.

So there we were sitting in the car in the way home. And I was I could hear this funny little sound. I said “Is that The Beatles?” And it was.

And they sounded like chipmunks because everybody sounds like chipmunks with a cochlear implant. And it's very high pitched. But it was definitely them. That was a very exciting moment.

JIM

I can imagine a joyful moment. They never discovered why you lost your hearing did they?

AMANDA

No, it can just happen. It's very unusual. But it can just happen. It might have been a viral infection. I had so many tests, and every time I moved because you move as a doctor a lot, and they want to do all the tests all over again. And eventually I said no. And I put a stop to it. Because actually, it didn't matter to me anymore what had caused it. The challenge I had was living with it.

JIM

Yeah, of course.

AMANDA

And the test wasn’t going to help with that.

JIM

Dr. Amanda Kvalsvig is with us.

Not all deaf people want hearing aids, or cochlear implants, we should mention that, I suppose.

AMANDA

Yes, it's really important to recognize that not everybody wants sound. And not everybody needs sound. And a really good example of that is deaf people who have grown up in the deaf community, who's whose first language is sign language. They have complete communication, they have a community, they have all those things around them. And they may well say, and often they do say, I don't need any more than that.

This is why it's such an individual experience. My experience was quite different. It was a terrible loss and so cochlear implants have been a tremendously lifesaving and life enhancing thing for me. But that's absolutely not true of everybody.

JIM

Yeah. No, I've read a bit about that.

The Southern Cochlear Implant Programme, which you're associated with, helps 1200 people I was reading, but of course it can't get them all cochlear implants. They're expensive.

AMANDA

They are. And there's always a waiting list. And I know, I remember that feeling of being on the waiting list in the UK and then here. And it distresses me greatly to think of people just kind of waiting and waiting - some for months or for years - to get that reconnection.

It is really hard to think of. I think it's really important to recognize the importance of funding these operations because of the absolutely enormous impact they have on people's lives.

JIM

Yes, these people who are living their lives in silence they don't want. You are reminded of that silence every morning, I assume because you don't sleep with them in. I imagine you will still know what deep silence is, won't you?

AMANDA

That’s right. So that's the important thing to realize if you meet a cochlear implant user, they are still deaf. I'm still deaf. I always will be deaf. But now I have some access to sound when I switch the processor on.

It's completely silent for me at night - actually I would say it's not silent. I have tinnitus ringing in my ears. And that's been there for decades now and I learn to switch it off.

But aside from that, I don't hear anything for quite a large part of each day because I haven't got my processor on.

I'm still a deaf person.

JIM

The oldest person ever to receive a cochlear implant was 103 I was reading so you're never too old to get one. That's interesting.

AMANDA

That's fantastic. Do you know how it went for them? Did they like it?

JIM

Yes. And there was a 102 year old as well. And I'm pretty sure that 103 year old still alive.

AMANDA

Oh that’s wonderful.

JIM

Now Loud Shirt Day, which has been the fundraising day for cochlear implants. I think it still is - it's not till later in the year. But I was thinking, you know, I've got a variety of loud shirts. And I'll probably think about the cause when I wear them now. Imagine if everyone who bought a loud shirt gave $1. I mean, maybe the stores could have donation jars, it's not a bad idea. And maybe someone thought of it.

AMANDA

I think that's a great idea. Maybe there has. I too have a stash of load shirts, which I make sure I'm always wearing on Loud Shirt Day. And but I think the idea of getting just a small donation from lots of people is so effective, isn't it?

JIM

You’ve chosen a song for us. Now, you were a singer and a violinist. Out of interest, do you still play?

AMANDA

I played the violin not still, but again. I've picked it up again. It's very different.

I can't really hear pitch, so that's a challenge for violin playing. And that it's quite emotionally challenging thing to do. But it is also so lovely because it's that connection with who I used to be.

And I still have some motor memory that can play the notes and so I won't ever perform that, but I get so much pleasure out of playing a Bach Partita or something that I used to play and just feeling that happening.

JIM

You would hear the notes in your head from memory of the old days differently from how they come out now? I'm just trying to work that out in my own head.

AMANDA

Yes, exactly. So it doesn't sound the same. And also, the tone of the violin sounds different and very screechy, I have to say.

Now unkind people would say that a violin always sounds very screechy and horrible, but I would never agree.

I love the sound of the violin, so when I'm playing or listening to music, really, I'm remembering and remembering what a violin sounds like rather than hearing it in that instance.

JIM

A violin sounds marvellous. I too, was a - poor - violin player, so I'm a fan of the violin. I'd never say it screeched. But if the implants aren't great at replicating real world sound, and pitch and timbre and so on, can you go to an orchestral concert, for example Amanda, and enjoy it?

AMANDA

I stopped going to concerts, I found it very distressing. And so sometimes I do want to and sometimes I don't.

I have and have always had a good memory for music. And that was that was helped by musical training, I think. So in fact, when I went deaf I effectively had a whole library of music that I could just listen to in my head, because I could remember it clearly enough to do that.

And so, when I listen to music now, I find that if I listen to music that I used to listen to or play a long time ago, I'm hearing it really, really well. I suspect because I'm remembering it, as I'm listening to it.

But if I listen to something that I didn't know before, it's quite hard to make sense of it sometimes. And that goes through, I’m now a woman in a time warp really, because there's a whole lot of music that's been created since I went deaf that is quite hard for me to access. I must be the only person in the world has never heard a Taylor Swift song. I might try, but I'm probably the only one.

JIM

At least you're stuck in a quality time warp.

AMANDA

Haha. Oh, I remember all the bad stuff too unfortunately.

JIM

Well, you've chosen a song for us today, which is the biggest selling jazz single of all time. Can you tell us why this is your musical choice?

AMANDA

This song I've chosen for cochlear implant day is Take Five by the Dave Brubeck quartet.

There's more than one reason for me to choose that one. The first is I’ve known this music my entire life. My parents used to listen to jazz when I was a child. And this is the music I used to hear drifting over when I was laying in bed at night. And I love hearing it now because it reminds me of my childhood. And it reminds me of my dad who's not with us anymore. So it does have that very strong emotional connection.

But there's a second reason which is that - and you may not have known this – it is an excellent piece to listen to through cochlear implants. And I discovered this really quite by chance. But when I think about it, it's got a logic to it. Would you like me to explain that?

JIM

Well, we know it's five beats to the bar, can you explain the rest?

AMANDA

Okay. The thing about listening to music with a cochlear implant is that the implant will do some things very well, and some things less well. So one of the things that does really, really well is rhythm, it gives you rhythm really, really clearly - anything percussive, you can hear really clearly.

Something it doesn't do as well is melody. And that's because the pitch information isn't as precise as it could be.

The third thing is that the timbre of the music, the instrument that you might be listening to, and that's very variable. So some instruments, it's transmits really well and some it doesn't.

So coming back to Take Five you can see it's got the rhythm, the rhythm is right up in front there, you've got the brilliant 5/4 beats - the whole thing as it is a rhythm piece, really.

In terms of the melody, it doesn't depend on the melody. So there is a melody from saxophone, but you don't need it and if you know what it is, you can understand the piece. And then the timbre is also really good to manage, because it's only got four instruments, it's a very clean sound. So that works really well for a cochlear implant processor as well. So it's great hearing therapy, as well as being a fantastic piece of music.

JIM

Right, so you fill in the gaps in a very interesting way when you hear this. Can I ask you a question? You are good on the violin, could you have played this in the old days? Because when they tried to record it, the Dave Brubeck quartet, they couldn't for a long time. It took them ages to get it right. So it's a kind of symbolic music choice of yours. They got there in the end.

AMANDA

Yes, yes. Yes. I know they wanted to do this because they wanted to showcase their ability to play and to improvise in 5/4 and it just didn't work for a while and then suddenly it did. You get a feeling when you listen to it of the excitement of that piece that they're creating.

JIM

So today's the day. Cochlear implant day and I suppose money is the issue. It always says isn't it with access to medical services, so you could use more money basically.

AMANDA

It's true of every single health issue, and that's what funders have to manage. I think with cochlear implants, sometimes it gets underestimated. The wellbeing impacts of losing hearing get underestimated. And so that's the point that I’d like to make really strongly.

Hearing is something that's very central to people's lives. Because it's communication because it’s things like music, and I would like to see much more funding coming through to support people that are currently living in silence.

JIM

You're a great ambassador for the day. Thank you, Amanda, very much for telling us your story and joining us.

AMANDA

Thank you. It's lovely to talk