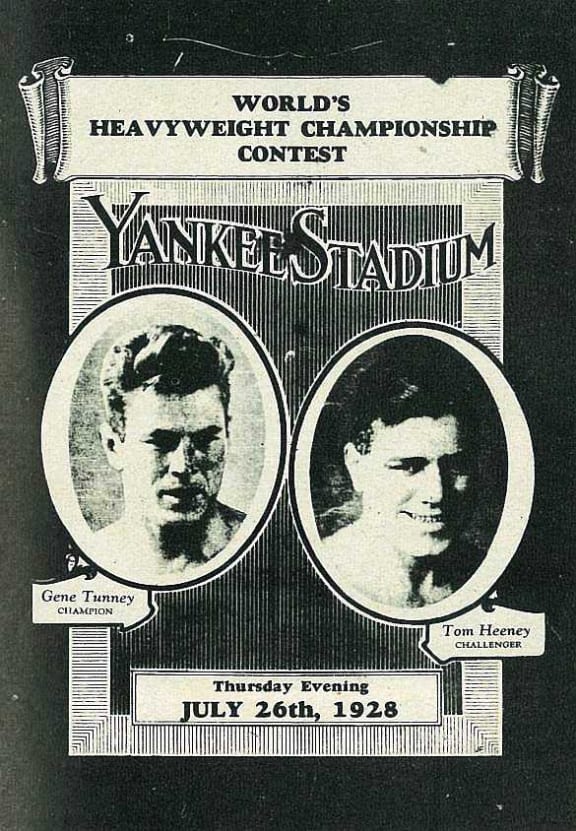

Ninety years and three days before Kiwi boxer Joseph Parker lost to Dillian Whyte, former Bay of Plenty plumber Tom Heeney fought for the world heavyweight crown at New York's Yankee Stadium.

In the early 1920s, Heeney, aka The Hard Rock from Down Under, fought with great success in New Zealand, Australia and Great Britain.

In 1928, he challenged US world heavyweight champ Gene Tunney.

Heeney was given his ‘Hard Rock from Down Under’ moniker by New York journalist Damon Runyon (who later wrote the stories which became the musical Guys and Dolls).

He was boxing in New York during "the golden era of boxing", says Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision's Sarah Johnston.

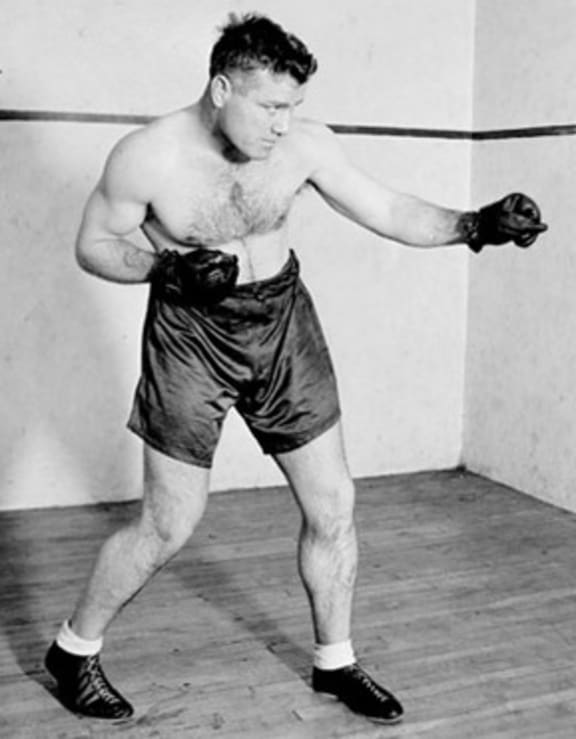

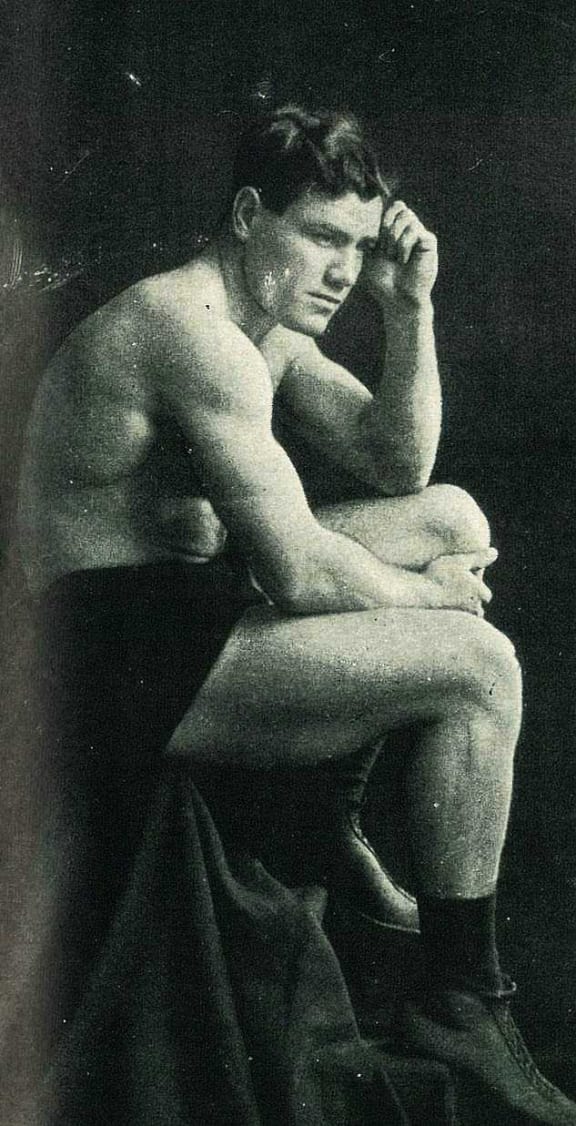

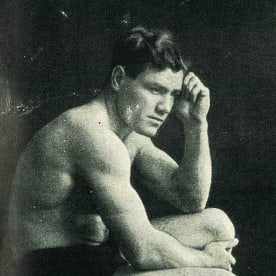

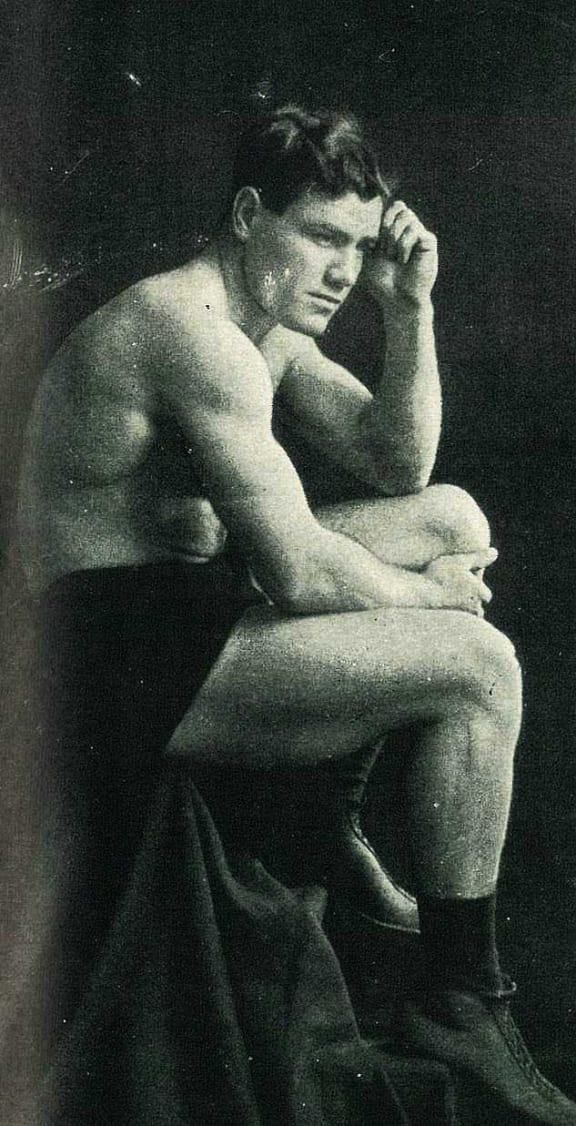

“He was a plumber from Gisborne originally, a rugby player, a very fit chap … he’s quite the specimen.”

Heeney's match against Gene Tunney was held at New York’s Yankee Stadium and attended by 46,000 people,

Back in New Zealand – in what were the early days of radio – people listened raptly attentive to the broadcasts.

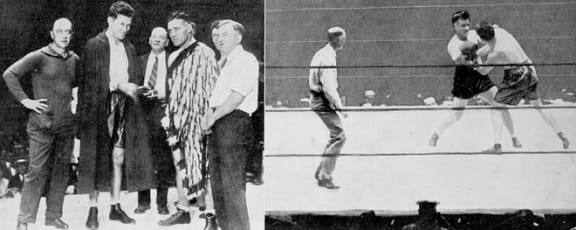

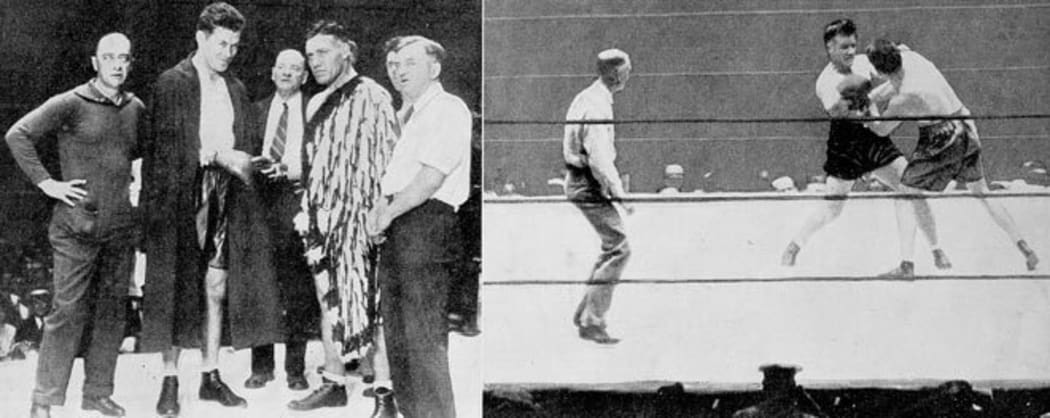

Tom Heeney versus Gene Tunney 1928 Photo: Te Ara

Heeney entered the ring with a Māori cloak draped over his shoulders, sent to him by Hēni Materoa Carroll, the widow of pioneering Māori politician Sir James Carroll.

He fought hard, but the fight was stopped in the 11th round as Heeney was bleeding heavily from an eye gouge.

Gene Tunney was awarded a total knock out and won the match.

Yet Heeney's story does have a happy ending, Sarah says.

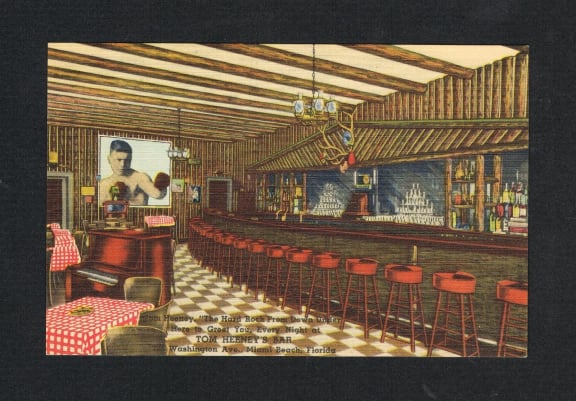

“He seems to have invested his winnings pretty wisely ... US$100,000, which is apparently about $1.5 million now.

“He came back to New Zealand and had a huge hero’s welcome, even though he lost the fight, especially in Gisborne, of course … Then he went back to the US, took out citizenship, settled in Miami and bought himself a bar.

“He became good friends with Ernest Hemingway, of all people, and used to go fishing with him.”

In a 1969 radio interview, Heeney explains how his manager tested him in Britain to see if he was good enough to try his luck in America:

"I didn't know this [at the time], but my manager went to [American boxer Tommy] Gibbons and said ‘I want to see what you can do with Heeney, belt him, knock him out if you can’.

“Every time we boxed I thought 'Geez, this guy’s a tough guy, he gives me holy hell' … So after Tommy Gibbons fought and he knocked [English boxer Jack] Bloomfield out in the fourth or fifth round or whatever it was, my manager asked Tommy Gibbons what did he think of me.

“I never knew all about this, Gibbons was doing his best all the time with me.

“They call me the Hard Rock from Down Under. I could take a good punch, and that’s why Gibbons told my manager ‘You take him across to America, he’ll do all right’.”

Watch some of the Heeney v Tunney world title fight:

During the world title fight, the shortwave radio transmission in New Zealand cut out, but luckily announcer Clive Drummond – a former WWI telegraphist – was able to transcribe the fight from the Morse signal.

Unfortunately, as Drummond describes in the second clip, this led to some premature celebration:

New Zealand's 1928 World Heavyweight boxing challenger Tom Heeney Photo: Gisborne Photo News

“The servicemen had made very special arrangements to pick up the ringside description by shortwave, but unfortunately the conditions were unsatisfactory.

“We had to rely entirely on the morse signals being sent out from the ringside describing the fight.

“I’m afraid in transcribing the Morse signals I anticipated the result by about five or six rounds by virtue of the fact, of course, that although the Morse signals were fairly fast in transcribing, they’re really slower than dictation speed.

“In the fourth or fifth round I was saying something like this – 'They’re coming out now for the fifth round'. The Morse signal coming in very slowly said ‘Tunney is out...’.

“Unfortunately those listening in didn’t wait for the remainder of the sentence. As soon as they heard 'Tunney is out' there were celebrations everywhere.

“It wasn’t until some minutes after that they found that the fight was still in progress.”

In the third cut – from the 1969 interview – Heeney recalls Tunney’s eye-gouge tactic which may have cost him the fight:

“During the war, I met Gene Tunney. And he said ‘Well, I didn’t’.

"To make a long story short, I said, ‘Well, if you didn’t then somebody else did’. All I know is that my eyelash got caught under my eyelid and I couldn’t get it out, and so I put my big glove and tried to hook it out with my thumb so I could see’.

“If you can’t see, you can't fight.

“I never knew anything about putting your thumb in your eye. You don’t do it in your punch, you just do it. When the referee says break, that’s when you do it.

“They guaranteed me 100,000 win, lose or draw and $5000 for picture rights. But some smart alec got in there and beat me out of my $5000 for the movies.”

Listen to writer Lydia Monin talking to Chris Laidlaw about her biography Tom Heeney: From Poverty Bay to Broadway back in 2008:

Tom Heeney: From Poverty Bay to Broadway

Tom Heeney: From Poverty Bay to Broadway follows the life of one of New Zealand's most colourful sports personalities from a labourer's cottage in Gisborne to the nightclubs of Broadway. Audio