A high-profile ecologist says New Zealand's Predator Free 2050 goal is feasible, but has voiced concerns about the possible use of gene drives as a means of achieving it.

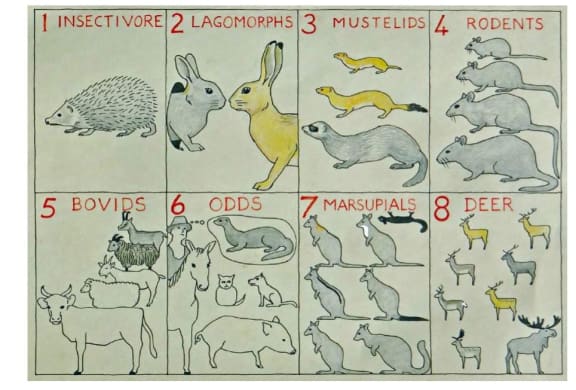

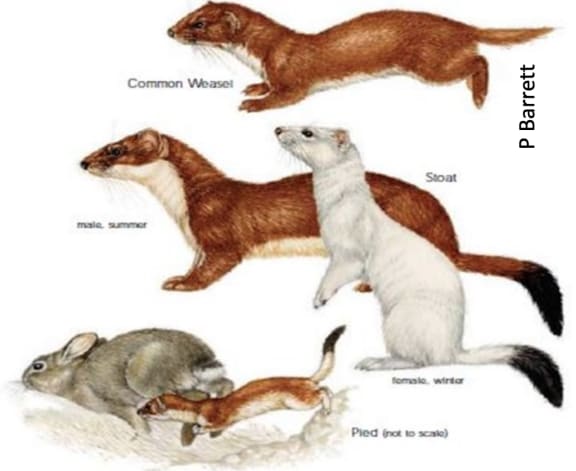

Professor Carolyn King is New Zealand's foremost authority on invasive mammals and world-renowned for her contribution to ecology - especially mustelids – stoats, weasels and ferrets.

She began her career in Oxford, and was studying weasels in 1971, when she was asked to come and help us get rid of stoats in New Zealand.

She wrote the first ever book on predators in New Zealand Immigrant Killers in 1984 and then The Handbook of New Zealand Mammals (1990), she’s is now working on the third edition.

But her most recent published book is called Invasive Predators in New Zealand - Disaster on Four Small Paws.

She told Jessie Mulligan the country's goal of being predator free by 2050 was terrific, but the technological means of achieving it didn't seem to exist. That wasn't to say the means wouldn't be attained as efforts to eradicate pests continued.

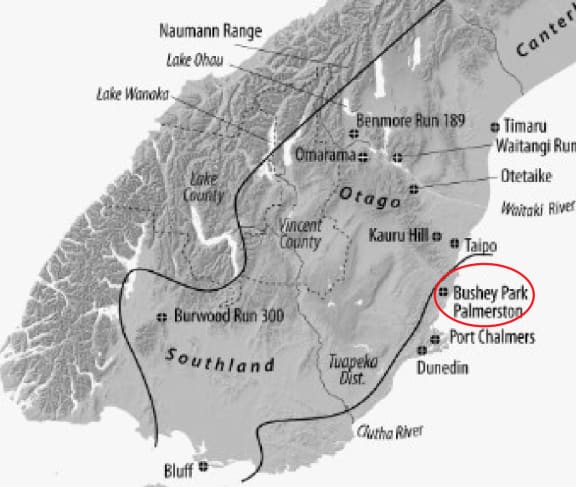

In her experience rats were far more numerous in forests and more of a problem that stoats, which were more of a particular problem to some fauna species. Two species of rats dominated the landscape in New Zealand - large Norway rats, which live in sewers and around dumps, and ship rats, which live in forests and can climb into trees and kill off bird populations.

Ferrets live in open country endangering lizards and bird nests on ground. Weasels, being smaller and unable to tackle bigger native species, have not proliferated around the country as much as stoats. All of these pest species needed to be tackled in unison, as removing one species would just benefit the other, she says.

“It isn’t enough to just to remove a few predators like possums, rats and stoats, there are other things that come in and take over when those disappear and in the meantime there are other things like herbivores destroying the forest, the trouble is you just can’t change only one thing.

“All of those animals belong to an interconnected community, you tweak one corner of it and something happens in another corner."

King says this is observed when farmers get rid of possums, only to find a subsequent major increase in rats.

“Possums are bigger than rats and they compete with them for food and it’s always to the rats’ advantage when the possums have gone.”

To deal with these populations effectively would involve a huge effort, employing tactics and technology other than just dropping poisons across vast tracts of land.

One option is the use of gene drives - a type of genetic engineering technique that modifies genes so that they don’t follow the typical rules of heredity. Gene drive technology dramatically increases the likelihood that a particular gene being passed onto the next generation, allowing the genes to rapidly spread through a population and override natural selection. Using the technology can cause extinction.

It's a technology that offers options, but King is hesitant to give it her approval, due to the inherent risks involved.

"I am very concerned about the possibility of people getting carried away by genetic modification. There's a lot of talk about gene drives, modified genes that can be introduced to a population. They're trying some in Australia for example with the Daughterless Carp Program and these are fish that can produce sons but not daughters. So if you have a whole population with one gender, than sooner or later the population will die out, without you having to set traps or poisons.

"So, that's the aspiration and I'd love to see that happen, but I don't know that it's possible yet. The thing that worries me is that a gene drive is something that you release into the general population and after that it becomes self-perpetuating. If it does the job that's fine, but if it gets out there and it doesn't do the job you can't call it back.

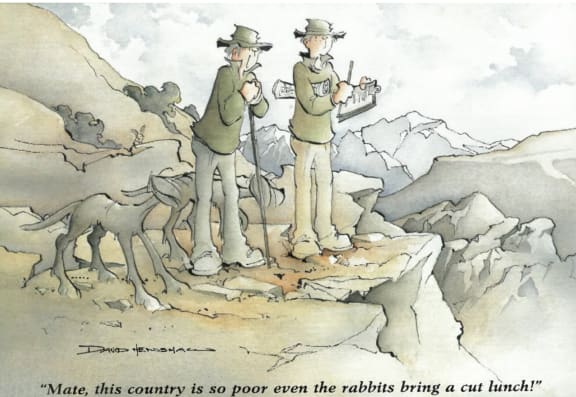

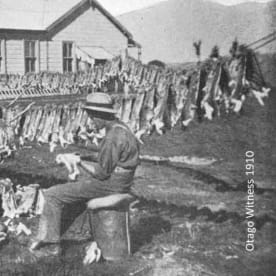

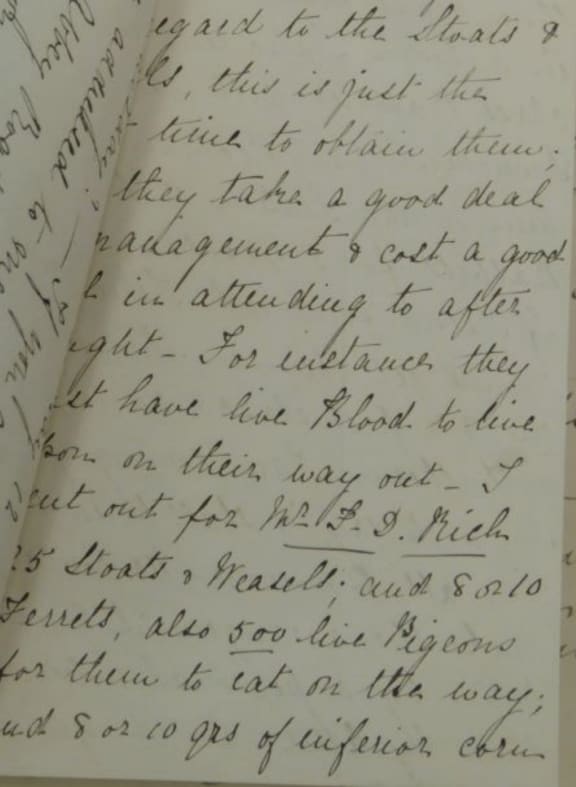

"Then we're into a 21st century mistake that they made in the 19th century bringing stoats in, in the first place, because the guys who brought them in where convinced they were the natural enemies of rabbits. Too many rabbits and their answer was we haven't got enough stoats. So they brought in more stoats and it didn't work.

"So the worry is bringing in any self-perpetuating weapon, which is very attractive because you don't have to put money and manpower into distributing it, may get away from you, doesn't do want you want it to do and becomes a real threat."