University of Canterbury Engineer Dr Volker Nock has been awarded a Rutherford Discovery Fellowship to speed research into containing kauri dieback and myrtle rust. In both cases fungal pathogens infect the tree by growing long arms, known as hyphae - which are a bit like pressurised drill bits.

Dr Nock joined Kathryn Ryan to describe how he and associate Professor Dr Ashley Garril are learning to blunt the force of the infection with a lab on a chip approach.

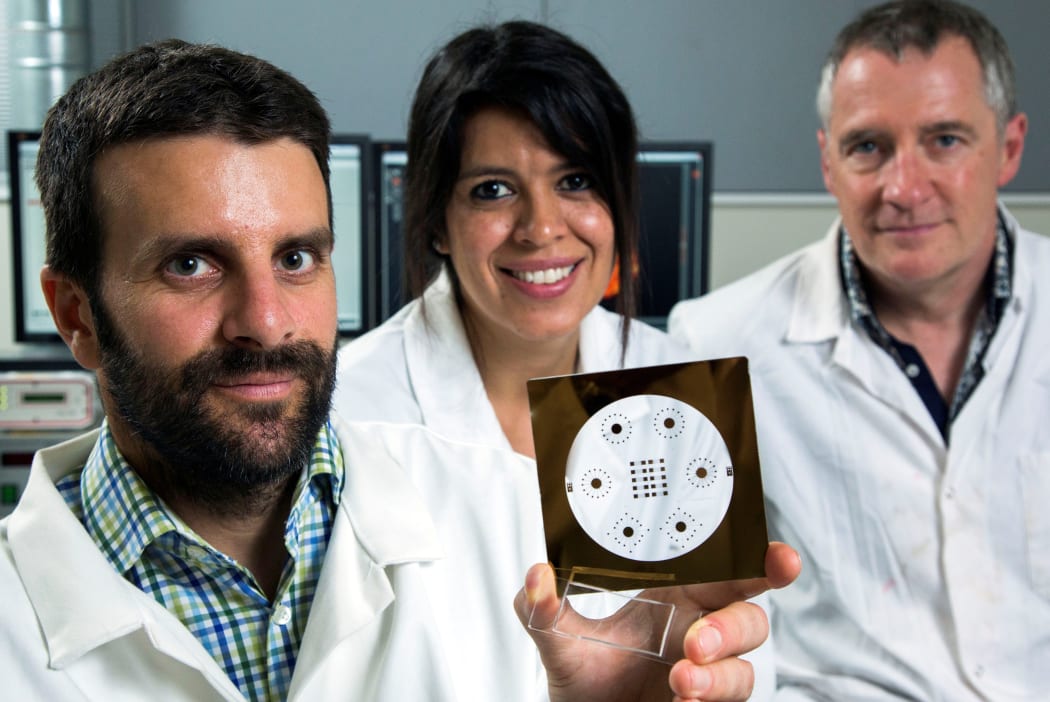

Volker Nock, Ayelen Tayagui and Ashley Garrill - their work on lab-on-a-chip is an engineering and biology collaboration. Photo: University of Canterbury

He says that while in myrtle rust, the leaves are attacked, Kauri dieback sets in at the roots.

“You have to imagine it a little bit like a single cell, very small, that finds its way to the roots and then grows into these long tentacles which are very thin - thinner than a human hair - those are used to penetrate into the plant tissue and feed on the plant’s cells.”

Kauri dieback is lethal to the tree and currently there is no cure for it. The treatment is to inject phosphate into the trees, but Dr Nock says that only contains the disease, it doesn’t cure the trees.

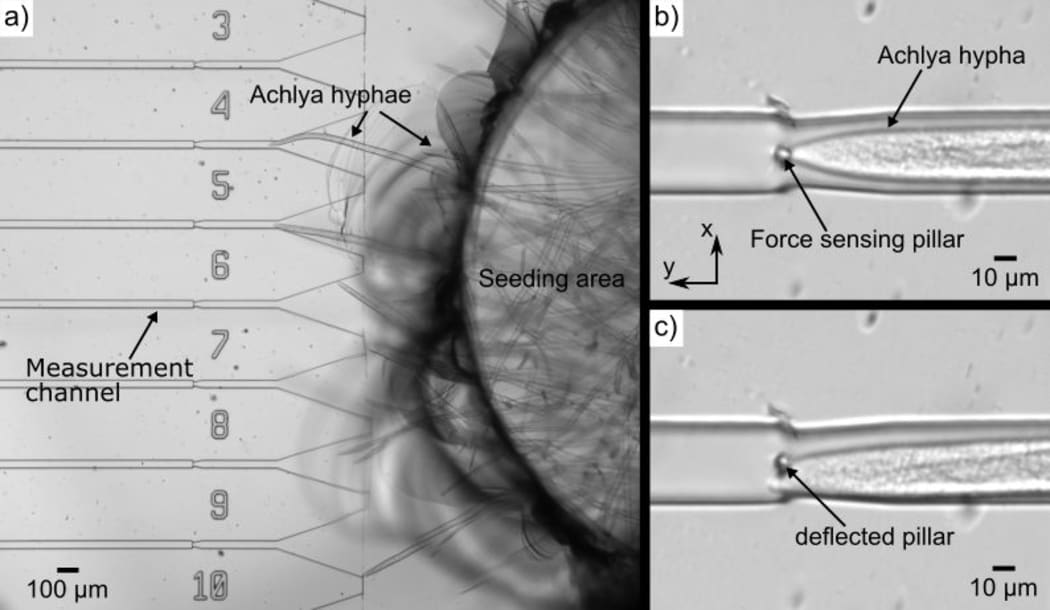

He explains that hyphae spreads a bit like a drill, with the tip burrowing through the plant.

“The force that they exert helps in penetrating the tissue, and that force hasn’t been characterised very well. It’s a significant force for the size of the structure that we’re talking about.

“So we have these very small force sensors that we could apply to these tubular cells that no one had tried to use before.”

Dr Nock says the experiment has been surprisingly successful.

“At the moment that’s really helped us understand some of the fundamental biology in terms of how these cells generate the force they need to penetrate the plant.

“The next step in this, and this is what I’ve proposed in my fellowship, is to use this as a screening platform. If we expose the fungi to compounds that we find in nature, for example, can we reduce the force they can exert. It’s sort of a natural treatment to prevent them from being able to drill into the tree.”

What it looks like when the fungi starts growing lots of these drill bits (hyphae) on the chip. Photo: Supplied

In a basic sense, he’s proposing to blunt the drill that penetrates through the trees.

Dr Nock says that, in theory, it shouldn’t matter how large or old the tree is for the process to work.

“I had a very moving visit to Waipoua Forest where the trees are massive. It’s really hard to imagine how a single cell that’s invisible to our eyes can more or less kill a tree that’s been standing for more than a thousand years.”

He says that with the current rate of Kauri dieback affecting trees, it’s a bit of a race against time to treat them.

“Any treatment that we can come up with will be better than none, which is the current case. It’s a question of how quickly and how efficiently can we come up solutions.”

Related stories: