If you try and compare your life to that of Louis XVI you might think that there's no comparison. The notorious French king had riches, servants and palaces, including that epic one at Versailles.

Yet while Louis XVI was unbelievably rich, before his unfortunate appointment with the guillotine he lived in unsanitary conditions in a time of horrifically bad healthcare.

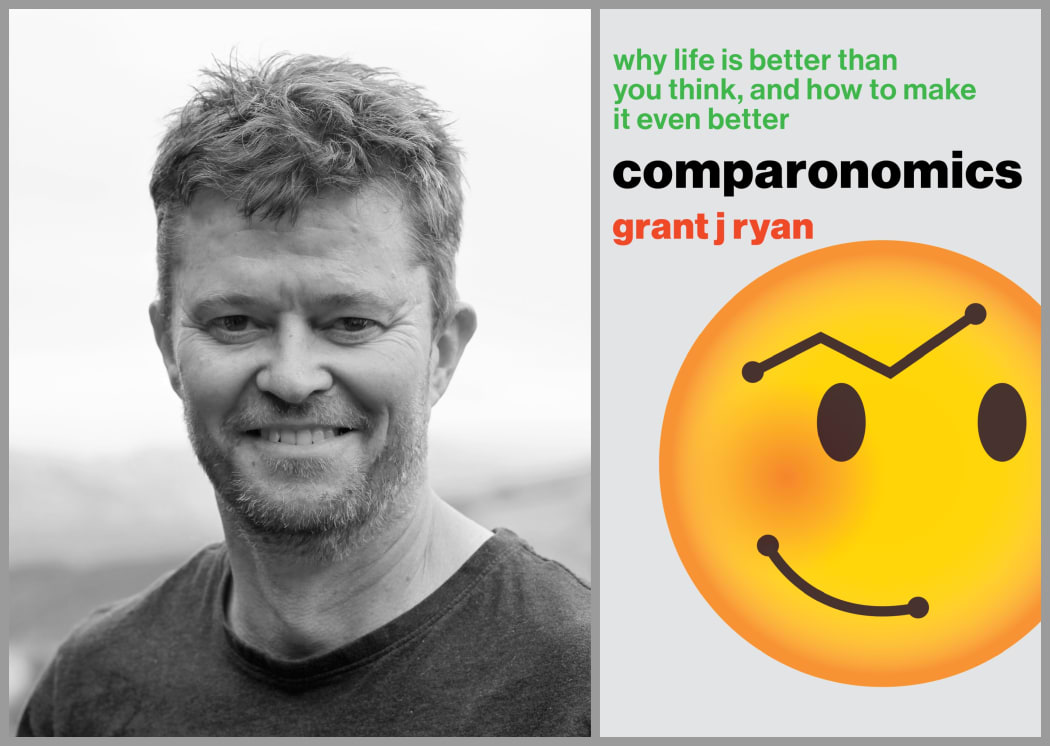

Economist Grant Ryan hopes his new book and online graph-making tool can help people stop comparing their own lives to others with a method he calls Comaparonics.

Louis XVI in Coronation Robes - a 1777 oil painting by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis Photo: Public domain

Comparing our own life to that of an 18th-century king highlights the fact that many services we now take for granted would have made rich men hundreds of years ago green with envy, Ryan tells Nine to Noon.

“I just look at the way that economics measures things that are important to us and it misses so much. I wanted to, rather than being an expert explaining why I think something’s different, make up a little tool and people could play a little game and work out just how their life compares.

“The King Lou example was one where you take someone who was one of the richest people in the world. He was so rich the peasants decided to chop his head off. If you’ve been to his palaces you can kind of see why.

“But when you look at those palaces and you see the intricate gardens out the front, they were designed as the most luxurious way to defecate because they didn’t have flush toilets. The health and sanitation were horrific.

“The fastest way he could get around was on a horse and even his food, people might say it was fit for a king and he had 300 people making it for him, but if he went into a modern supermarket he’d be blown away by what we have access to. And those 300 people who were preparing it for him didn’t know it was a good idea to wash your hands and what he got [served] would be illegal to serve to prisoners.”

In today's world, you don’t need to be rich to be literate and have specialised knowledge, Ryan says. Even the poorest in society have opportunities to access information and education.

Our collective wealth has progressed even since the '70s, he argues.

“Let’s have a look at the 1970s. When I was growing up you had to be rich to have a set of encyclopaedias and now literally we have something [the internet] that is 100 or 1000 times better and it’s virtually free. But according to economics, it doesn’t really account for anything and that seems a very weird way to measure progress.”

Even with strained health systems, people live about 10 years longer than we did in the 1970s, Ryan says.

“We might complain about how long it takes to get a hip replacement, but they didn’t get them back then, they died in agony.

“Again, economics isn’t geared to measuring the fact that we like living 10 years longer.”

Photo: Supplied

As human beings, we're programmed to compare what we have to others, feel a "natural level of grumpiness" about what we see no matter how good our lives are, and seek more to satisfy ourselves, Ryan argues.

“We have a biological preference for negative information because that’s what helped us survive when we were getting hunted by tigers and things."

In terms of wellbeing, we are the richest 1 percent of the approximately 100 billion people that have ever lived and we don’t really realise that, Ryan says.

“What would a billionaire have paid two years ago to have a Covid vaccine or treatment that halves their chances of dying when they go to the hospital? They would have paid a fortune."

The stress of modern life is real, Ryan admits, but part of the problem is social media amplifying our simple human nature to want more than we have.

This skewed perspective even stops people from voting for politicians who favour a more progressive and egalitarian taxation system, Ryan says.

“When you work out that’s not winnable you can then have a bit more perspective and I think that makes it more likely [that people will support] a progressive tax system."

Most of us choose less progressive options because we feel stressed about losing money, Ryan says, but if we understood that, in comparative terms, we are actually doing really well, we could then allocate resources to other problems.

For Ryan, becoming aware of negative views about our own life is important. When we do, we can address it.

“When I feel like the world has turned to custard and you get into a spiral of doom, actually I’m just being a human, it’s what we’re programmed to do. It’s just a little check on why you’re feeling bad and what you can do about it."

The measures we use for economic productivity are profoundly flawed and put too much pressure on us, he says.

“There is no end to the things people tend to keep wanting. As soon as they get rich enough they’re like ‘okay, I need to just need a little bit more and a little bit more.

“The way economists measure productivity is so comically absurd… The reason it’s so bad is when they measure inflation year to year, there’s not much difference in what’s there, but when things completely change over time [the system is] not designed to measure that."