Three years ago, Hong Kong was rocked by protests that shook it to its very core.

It began with concerns about an extradition treaty with China, was fuelled by the disappearance of five booksellers and ended with a crackdown on freedom of expression.

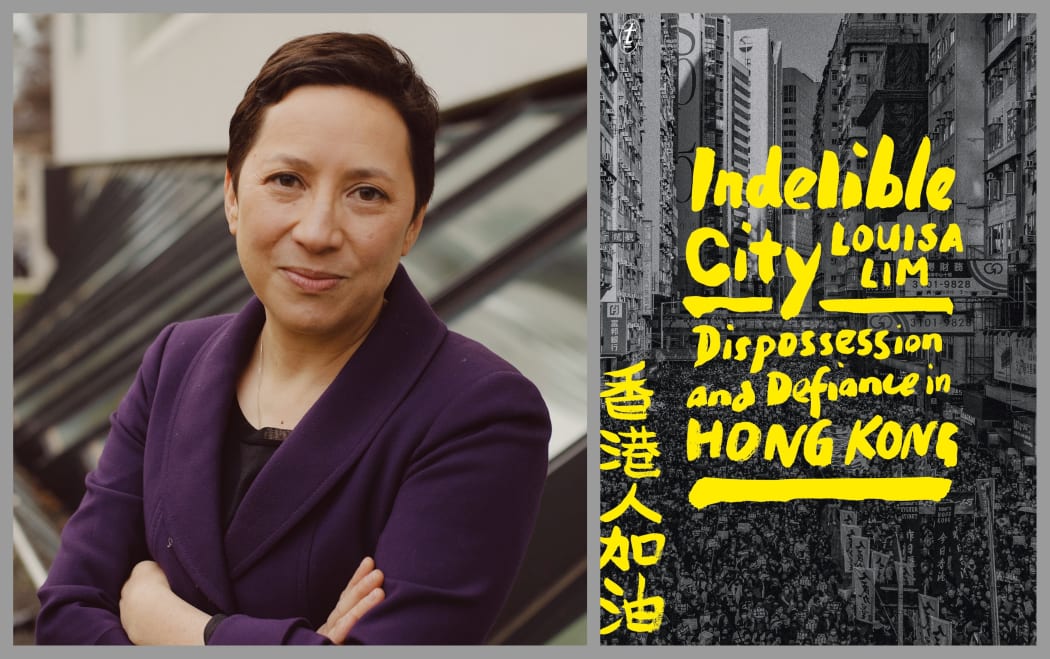

It also made Louisa Lim realise it was time to go back to the place she was raised and unearth stories about the identity of Hong Kong.

Her new book about the history, people and culture of her childhood home is called Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong.

Photo: Laura Du Vé

Lim was born in Singapore and at the age of five, she and her parents - Chinese-Singaporean and British – moved to Hong Kong in the belief it would be a good place for a mixed-race family.

“It's a very interesting identity. It's one that's changing all the time, and I think has changed in the last few years since the 2019 protests, just because so much of those protests were about identity.”

When they got to Hong Kong, they faced prejudice, Lim tells Kathryn Ryan.

One time at a teahouse, elderly women were so offended by the way she looked that they threw tea leaves at her.

“It was shocking at the time, then when I started looking at it, I realised there’s this sort of long history of discrimination against mixed race people in Hong Kong.

“[The history of prejudice was] so long that mixed race people historically have often kind of erased themselves from history, they've denied being mixed race, they’ve either taken on a Western identity or a Chinese identity, so that was sort of still the legacy that existed when I was a child.”

But even the history of Hong Kong itself was deliberately veiled in the education system because the colonial government feared it may turn people against the British, Lim says.

“Anything that we learned about China was quite negative. It was things like foot binding and rickshaws, things that painted China in a bad light, Chinese people sort of as cruel and savage.

“Also, I think the colonial government didn't really want Hong Kongers to develop a very strong sense of distinct Hong Kong identity because it might make them harder to govern.”

Graffiti painter Tsang Tsou-choi, known as King of Kowloon, pictured in 2003 with his works. Photo: Ricky Chung/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

Lim says she wanted to focus on Hong Kong voices in the retelling of their history in her book, and part of that was exploring the life of Tsang Tsou Choi, who claimed the Kowloon peninsula had been stolen from his family when it was given to the British in 1860.

For half a century, he marked the streets with his family tree and the land his supposedly family lost.

“His handwriting was very bad, just very childlike, very lopsided, not beautiful at all, but he became this artist … and eventually he represented Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale and he became Hong Kong’s most valuable artist.

“I was just so fascinated in him because everybody thought he was crazy, yet he was really the first person to tackle these huge issues of territory and sovereignty and loss and dispossession, and to do it really, really publicly.”

In 2019, protesters echoed his method and vulgar language as graffiti spread across the streets and people resorted to saying ‘we really f---ing love Hong Kong’ as a code of defiance, Lim says.

People put stickers with messages in support of the pro-democracy protests on a "Lennon Wall" in Hong Kong on September 16, 2019. Photo: AFP / Nicolas Asfouri

"We were seeing these walls of calligraphy, sort of protest calligraphy that were appearing across Hong Kong, and they were called Lennon walls after a famous wall in Prague named after John Lennon.

"But these were Post-it notes that people were posting all across Hong Kong and they were all about the love for Hong Kong and swearing at China and things like that."

The new broad national security legislation imposed on Hong Kong was a threat to anyone who dared to say anything even remotely opposed to the mainland, Lim says.

“I really wanted to restore a Hong Kong voice to their own story and yet there were some things that people said that I just couldn't tell whether it could possibly get them in trouble.

“As people say, there aren't any red lines, it's just a red sea nowadays with red lines nowhere and everywhere. And the only way of ensuring safety is silence, and I didn't want to remain silent.

“For people inside Hong Kong, it can be really hard to speak, but for people like me outside Hong Kong, I think this liberates us if we want to use our voices and I wanted to do that.

“People are being arrested for waving banners, for having stickers with banned slogans on it.

“I think what we're seeing is just so far beyond what anybody imagined. It's deeply shocking. And there's just this very deep sense of loss for Hong Kongers, that they no longer recognise their own city.”

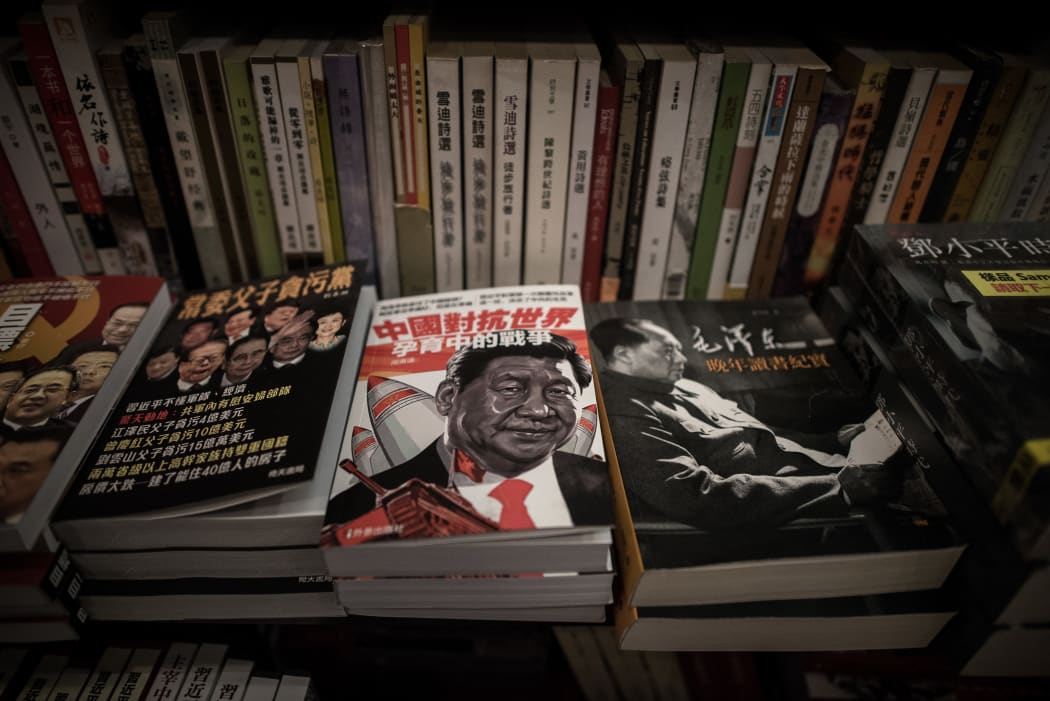

The disappearance of five Causeway Bay booksellers in 2015 shook Hong Kongers, who had seen their city as a place of freedom of expression, she says.

“Mainlanders would come over from Hong Kong to buy books that were banned on the mainland and they'd go to these little book shops.

Books about China politics are displayed in a books store in Causeway Bay district in Hong Kong on January 5, 2016. Photo: AFP / Philippe Lopez

“And in that case, there were five booksellers from one particular book shop who just vanished. And then they turned up on the mainland, in police custody. So, it looked like a rendition.

“It was a real sign of how much things were changing that even a small bookshop could be seen as a threat to state control and such action taken.”

That repression has been building up ever since, with zero Covid policies also used a means of social control, she says.

“We're seeing huge outflows of people. I think 150,000 people have left since the end of last year, and a lot of that is driven by the Covid zero policies. But there was a recent survey which said a quarter of Hong Kongers are now making plans to leave.”

Although, the growth of exiled communities of Hong Kongers doesn’t necessarily mean the battle is over, as one activist put it to Lim.

“He said ‘the battle will continue, it's just the battlefield is much larger now’ … I think we'll see more lobbying, we'll see Hong Kongers coalescing overseas.”

Louisa Lim is an award-winning journalist who reported from China for a decade and now teaches journalism at the University of Melbourne.