While the Middle Ages are seen as a bloodthirsty time of Vikings, saints and kings, and a society which oppressed and excluded women, BBC documentary maker and Oxford historian Dr Janina Ramirez reveals that medieval women actually fought Vikings, poisoned enemies, worked as spies and even became kings.

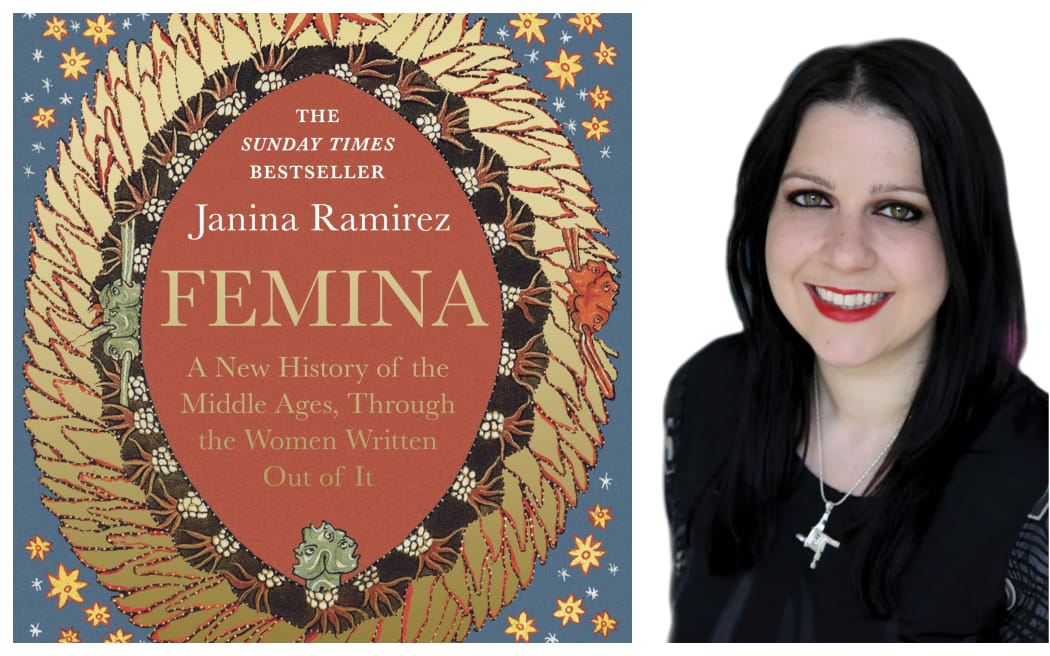

In her new book; Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It, Ramirez brings to life the medieval women that have been forgotten, underwritten, or deliberately erased from history.

Photo: Supplied

Ramirez tells Kathryn Ryan she came across the word Femina - the Latin word for woman - when she was searching through library catalogues from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Often when a book has been lost, destroyed or removed from a library, a reason is given, she says. The most common being heretical, because it was no longer considered orthodox. Other reasons included sorcery of witchcraft.

"But there was this term femina that was popping up, and it means that it was written by a woman, and therefore, is either destroyed or lost or not considered worthy of continuing to remain in that collection. So that got my hackles up a bit.”

With a fire in her belly, as she puts it, Ramirez set out to allow women back into the texts of history.

Margery Kempe

The first autobiography written in the English language was The Book of Margery Kempe, a “mystical” and “extraordinary” text written in the 14 Century, Ramirez says.

Margery, a “pretty well off but not an elite woman”, was somewhat of an entrepreneur, Ramirez says, and saw a trend in her lifetime of secular women turning to mysticism.

After having 14 children, Margery declared she was in fact a virgin and decided to become a mystic.

“She begins [to narrate] this sequence of experiences, encounters with Jesus with the saints. But around all of that, what you also get [in her book] are these incredible insights into real life for 14th Century women.

“We have this idea the medieval period is very parochial, everyone living and dying in sight of their local parish church. It's all Monty Python-esq. But with Margery, she travels up to Scandinavia, she does the Compostela [pilgrimage] over Spain, she goes all the way across Poland, Germany, France, and gets all the way to Jerusalem. And she does all this through walking, riding on carts traveling on a horse.”

The only surviving manuscript of Margery’s book was discovered in 1934 by a man named William Ignatius Butler Bowdon – who very nearly destroyed it.

“He’s rummaging around in this dusty cupboard trying to find [ping pong] bats and balls and there's two dusty old books in there. And he starts pulling them out in front of his guests, and he says, "I'm going to burn the lot of them so that I may find ping pong balls when I wish.

“But his guest is a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum and he cautions Bowdon and says 'I don't think you want to do that there might be something of real value in there'. Lo and behold, it was this dusty book.”

Among the books was the book of Marjorie Kemp.

Æthelflæd

Aethelflaed was celebrated in her lifetime as more illustrious than Ceasar, Ramirez says.

Aethelflaed as depicted in the cartulary of Abingdon. Photo: Wikicommons

“She had the utmost respect of people that she was fighting against. So, her reputation survived in a lot of Old Norse texts because she was battling against Viking incursions, but also in Irish texts, because she was well respected on over in Ireland as well. In England itself, that's where the problem came.”

The daughter of King Alfred the Great, after her husband’s death Aethelflaed became the Lady of the Mercians, ruling the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia until her death in 918.

As Aethelflaed had refused to subject herself to childbirth after the birth of her first child, in the only case in English history, her crown as Lady the Mercians passed directly to her daughter after her death.

Though, Ramirez says, she was eventually deliberately written out of the Chronicles by male rulers.

Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard was an “extraordinary polymath” who had almost more influence than any of her male contemporaries in the early 12th Century, Ramirez says.

Hildegard spent the first 40 years of her life in a predominately male monastery on very isolated hilltop in a remote part of Germany.

From a humble beginning healing the sick and learning about the natural world, Ramirez says an extraordinary mind emerged.

"I can't think of a person alive today that could rival Hildegard in the breadth of their knowledge.”

A scientist, Hildegard wrote the natural histories that still form the basis of herbology and an understanding of gems and minerals, Ramirez says.

"She wrote beautiful mythical works, but also philosophical works. She wrote to the emperor, to the kings and queens of the world instructing them on how to govern and she wrote music, the most extraordinary music, plays, poetry, and she was an artist."

Hildegard is one woman who hasn’t been forgotten, her legacy carried down by men, she says.

“This is the point of this book, it’s not a sort of male bashing book, it's an inclusive sort of feminist book in as much as through looking at the women you find the people that propped them up.

"It's not just women who've been excluded from history, people have been excluded for a number of reasons.”

Still today we are seduced by a great powerful man that dominates our historical narratives, Ramirez says. “But what if we look for everyone else.”

“What you find in this book is there were powerful, powerful women.”

It’s about readjusting the frame through which we look, she says.

"It's the same history, the same information and dates and facts but it's giving a different perspective that I think is much needed at the moment.”