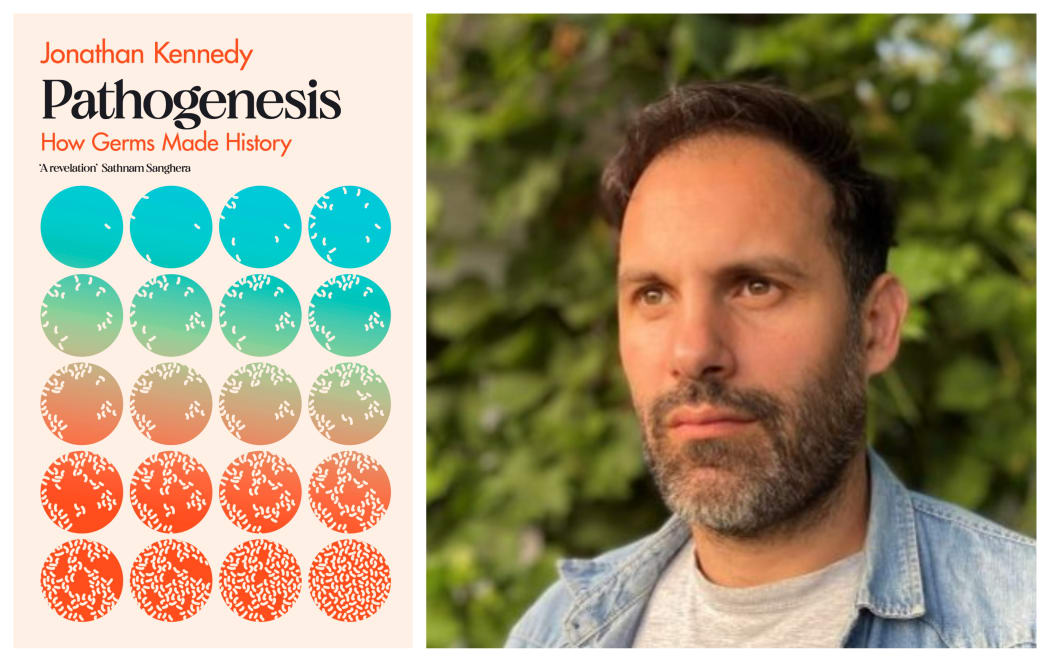

In his new book Pathogenesis Dr Jonathan Kennedy argues that Infectious diseases have been the driving forces of human history.

Diseases have shaped humanity, from the development of agriculture to the global rise of religion, he says.

Dr Kennedy is a visiting fellow at Queen Mary University, London where he teaches in global health policy.

Photo: supplied / twitter

The dominance of homo sapiens and extinction of Neanderthals was likely the result of disease, he told Kim Hill.

“I always went along with the dominant view that homo sapiens survived, whereas Neanderthals became extinct, because we were more intelligent.

“This is such a dominant argument that it's even inherent in the name that we give to ourselves, homo sapiens or wise humans, whereas the Neanderthals, in the 19th century were sometimes even referred to as homo stupidness. Stupid man or stupid humans.”

Over the last 20 years there's been an increasing amount of evidence that shows Neanderthals weren't that different to us, he says.

“They painted on cave walls, they used medicinal herbs to treat various illnesses, they buried their dead, they talked to one another.”

So why did they disappear 50,000 years ago? Most likely homo sapiens gave them diseases for which they had no resistance, he says.

“We had been separated from Neanderthals for over half a million years, we'd been living in tropical Africa, and they'd been in western Eurasia.

“We'd been living in totally different disease environments. And when we started to push out of Africa 60,000 years ago, we were carrying diseases that the Neanderthals hadn't developed any resistance to.”

When we met with the Neanderthals in the eastern Mediterranean, they died out, and we survived as homo sapiens came from a more tropical; microbe rich environment, he says.

Thousands of years later in the 14th century infectious disease wiped out two thirds of the world’s population, but the cataclysm of the Black Death also unleashed a period of extraordinary innovation and social change, he says.

“It basically kickstarted a series of events that over decades, and even hundreds of years created the world in which we now live, a world in which it's no longer a feudal society where you have these warring Lords a bit like Game of Thrones, and then at the bottom of the social pyramid, you have serfs who are working on their, on their little strips of land and just trying to try to scratch a living.”

Feudal society couldn’t function without plenty of serfs to exploit, he says.

“The serfs realised that suddenly labour was in great demand. And cultivatable land was really, really plentiful, so they struggled for the better terms.

“And certainly, in England, this led to a situation where 100 years after the Black Death, the vast majority of serfs have won their freedom.”

Human history from the adoption of agriculture about 12,000 years ago is punctuated by these devastating pandemics, he says.

“Infectious diseases have been one of the real driving forces of human history. And I think this is an interesting way to think about the world because often when we think of history, we focus on the role of great men and great women in really kind of rushing historical change.

“But actually, when we look at history through this perspective, we see that in many ways, infectious diseases, are the real tidal force that's pushing the past forward.”

Just as disease has shaped human society, so too has human collaboration, he says. Overcoming the squalor that accompanied the industrial revolution in England is an example.

“The industrial revolution reaches its height in the middle of the 19th century and you have unprecedented economic growth, you have this massive creation of wealth.

“But at the same time, health among the majority of the population, in Liverpool and Manchester, which are the centres of the Industrial Revolution, life expectancy for factory workers falls to 15 in Liverpool and 17 in Manchester. This is really, really catastrophic.”

The only way to overcome this massive public health crisis was through democratisation, he says.

“These new local politicians that were really driven by an ethos of public service. And they directly tax the middle classes and indirectly taxed the lower classes, the factory workers, and they spent enormous amounts of money on sanitation systems and drinking water, and then later improving health systems.

“And this is what enabled the UK to kind of have this massive transformation in life expectancy at the end of the 19th. And the first half of the 20th century, this this massive investment in public health and wellbeing.”

Covid reminds us, he says, that collaboration on that scale will be needed in the future with scientists predicting another Covid-like pandemic could emerge in the next 50 years.

“I'm certainly not the first person to say it but we need to rethink the focus that we have on economic growth and think about how that economic growth can be used to improve the health and wellbeing of the majority of the population because money in and of itself is of no use. If you're dying at a young age or living a very unhealthy life.”