It's generally true that the ability to get good sleep declines as we get older, says world-leading chronobiologist Philippa Gander.

One of the best-known ways to increase the amount of slow-wave sleep we need for essential "brain cleansing" is regular physical exercise, she tells Kim Hill.

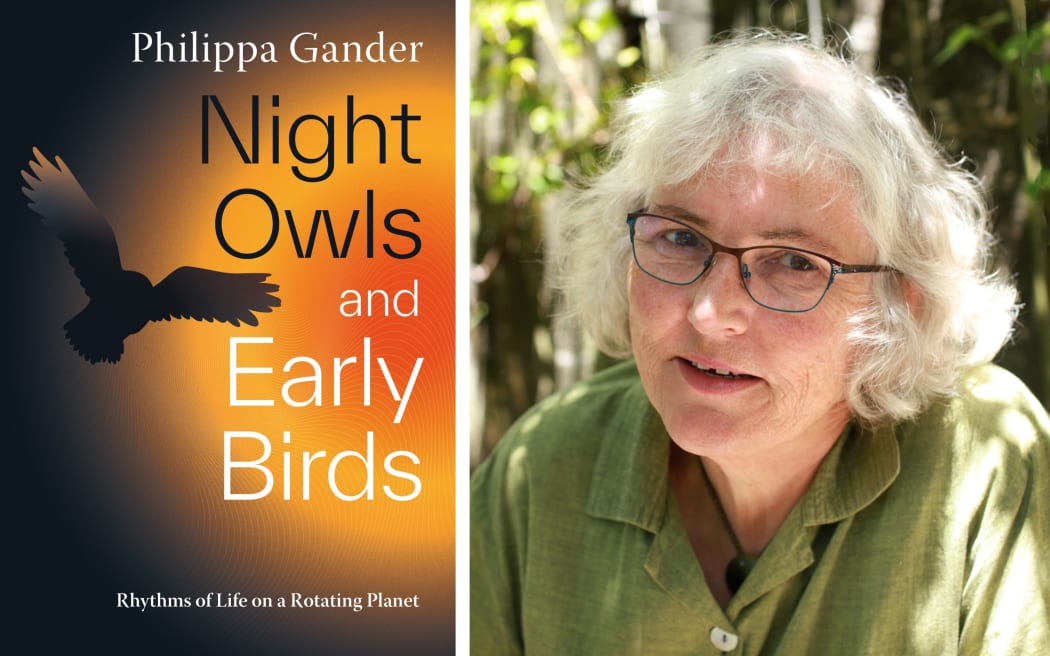

Photo: Auckland University Press/Julian Ward

Gander is a now-retired scholar of circadian rhythms who has studied horseshoe crabs and hibernating squirrels, jet-lagged pilots and space-station astronauts.

In her book Night Owls and Early Birds, she argues that to sleep better we need to reconnect with the biological cycles of the Earth.

Humans and every other organism on the planet have adapted to change in step with the rhythmic environmental changes, Gander says – day turns to night and seasons come and go.

"The way you function and feel will be changing across every day of your life. [It is] modified continually by little genetic clocks in every cell in your body."

In the past, exposure to naturally changing light intensity has kept us in synch with these rhythms, Gander says, but now artificial light is interrupting this process for humans and our fellow creatures.

During sleep, our brain recovers and even cleanses itself but we need to spend enough hours in the complex stages of sleep.

This doesn't have to be in one long stretch, though, she says.

Before electricity, it was normal for people to have a first and second sleep, especially during winter, and many non-human animals are polyphasic –get their sleep in bursts rather than a long stretch.

"Waking up in the night is not a problem – if you can sleep in in the morning and you don't worry about getting back to sleep."

Photo: Rob Potter

Napping is a 'built-in strategy" we can use to catch up on sleep but alas not to "bank" it, Gander says.

While some people, including shift workers and the sight-impaired, find it helpful to take melatonin, this natural compound is not a "magic bullet" for sleep, Gander says.

Melatonin is a "very active hormone" that has an interesting relationship with the master clock in our brain, but it can interfere with the reproductive systems of mammals so isn't recommended for pre-puberty children.

We also know it's not always a sleep hormone: "In nocturnal mammals, like rats… they have high melatonin levels at night when they're active ... I think that we have to be a bit careful about it."

Jetlag is the result of our circadian master clock struggling to adjust to a new time zone, Gander says, and even our body's organs each have different circadian rhythms that get pulled out of synch.

"It's not only that you're out of step with the outside world, you're out of step internally and that takes a few days to get back in, too.

"What you've got to do is give it as much stimulation from the environment in the new time zone, which means getting as much daylight as you can, trying to get on to the local routine. It won't feel good for a few days.

"The main thing is to get enough natural light exposure and as much exposure to local time as you can."

Professor Emeritus Philippa Gander was the inaugural director of the Sleep/Wake Research Centre at Massey University and in 2017 was appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the study of sleep and fatigue.