The "market fundamentalism" that has come to dominate American politics was bankrolled by American business for decades, a new book argues.

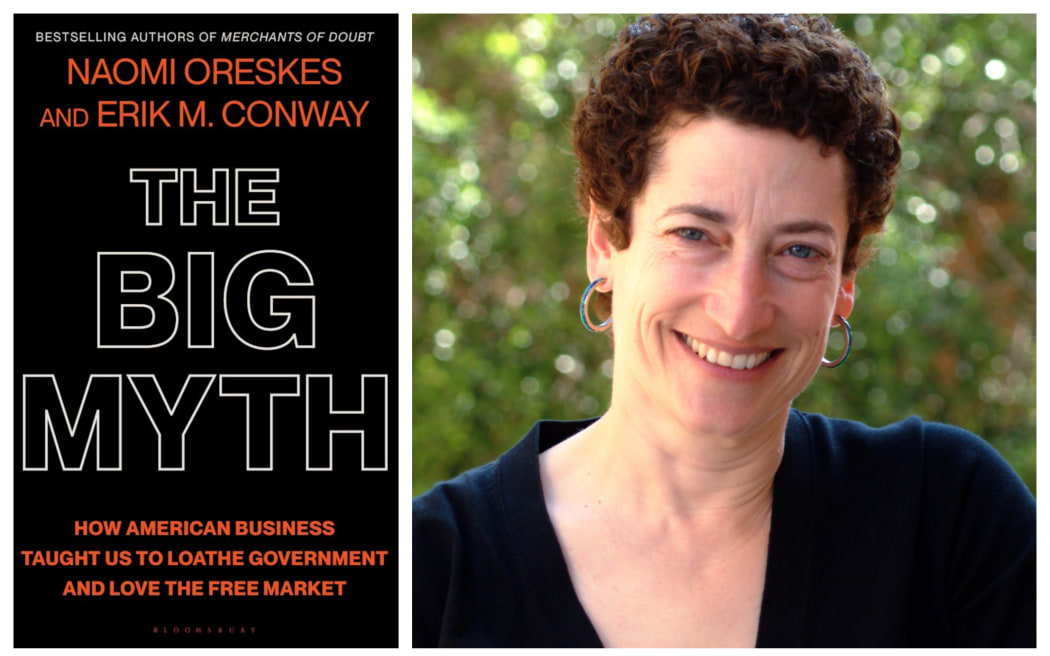

The Big Myth: How American Business Taught us to Loathe Government and love the Free Markets by Professor Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway outlines how these ideas took hold among America's policy makers.

America's most famous market fundamentalist Milton Friedman preached a concept called the indivisibility thesis, Oreskes told Kim Hill, in which he argued free markets were essential to a functioning free society.

Photo: supplied

“The claim was that free markets aren't just an efficient way to deliver goods and services, but they're the only way that does it that doesn't threaten our political and personal freedoms.

“And then this was then used as an argument for why you shouldn't regulate tobacco, or you shouldn't regulate fossil fuels. Because if you did regulate those products, you will be on the slippery slope to socialism.”

The idea in the US that capitalism and freedom are two sides of the same coin goes back to the early 20th century, she says, when organisations such as the National Manufacturers’ Association argued against labour regulation.

In the early 20th century the National Association of Manufacturers led a campaign against regulating child labour using the indivisibility thesis, she says.

“It wasn't that they were evil, terrible people who liked to exploit children. But that if you regulated the workplace, this would compromise freedom broadly.

“And so they begin to develop this argument as a way to push back against regulations that most people supported. Most people did not think child labour was a good idea. But rather than defend child labour, which was clearly indefensible, they come up with this theory, this argument that gives what seems to be a moral basis for what is really an evil practice.”

In the 1940s two Austrian economists, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek, added their voices to the slippery slope theory, she says.

Photo: HarperCollins Publishers

Hayek’s book The Road to Serfdom is cited as a kind of Bible of market fundamentalism, Orseskes says.

“But what we show in the book is when you actually read the book, you realise it's a much more subtle and nuanced argument than people hold.

“So von Hayek, did say that there are many areas where it's completely appropriate for the government to get involved, for example, preventing pollution, or preventing deforestation.”

The Big Myth says von Hayek’s arguments, without his caveats, were enthusiastically adopted by the American right.

“A group of American businessmen who are very excited by fanaticism for Hayek’s ideas, invite them to America where they promote their ideas, but they promote a bowdlerised, over-simplified, really dumbed-down version.

“In the case of von Hayek, they produce a Reader's Digest condensed version in which all Hayek’s caveats, all of his restrictions are removed, and it's simply turned into 'the government can do no good, everything must be left to the marketplace'. And then they make a comic book out of it, a little literal comic book in which they change the argument.”

Another influential book from the early 20th century is Little House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder which has been read by millions of American children.

The books were marketed as the true story of Laura Ingalls Wilder growing up on the American frontier. In reality the books were a fabrication largely written by Laura’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, she says.

“She took her mother's rough notes, and basically turn them into libertarian parables in which this family survives, by dint of individual hard work with no help from the government.

Friedrich von Hayek (Nobel prize winner for Economics). 1977. Photo: VOTAVA

“And that was false on at least two counts. First of all, the family didn't actually thrive, the family actually had a series of failures, it's actually a very sad story when you know the truth of it.

“And what little success they did have was, of course, made entirely possible by the US Federal Government through the Homestead Act.”

In the 1950s, Ayn Rand came on the scene with her book Atlas Shrugged, which has been deeply influential on the American right.

The Rand Institute distributes hundreds of thousands of free copies of her books, to libraries and schools across the United States, Oreskes says.

“She's also a complete hypocrite, because while she is writing these books, and screenplays celebrating radical individualism, she's also writing censorship codes for Hollywood.

"And we see this throughout the book that these people who claim to believe in radical forms of individual freedom, at the same time are working to censor other people's views.”

For example, Rose Wilder Lane worked with Herbert Hoover to try to blacklist a Keynesian economist at Stanford, she says.

“Because his textbook is proving very successful, and they want to ban that book. So, they're trying to ban books that they don't like, even when they're advocating for radical democracy and political freedom.”

Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom in 1962 gave further impetus to the movement.

“In the 1950s some of the best same businessmen who were correspondents of Rose Wilder Lane, Herbert Hoover, they begin to fund the Chicago School of Economics specifically with the idea that it would promote free market ideology that would be congenial to the American business community. And one of the people they support is Milton Friedman.

"And he writes Capitalism and Freedom based on a series of lectures that was in fact funded by these businessmen.”

Business has long been actively distorting the academic marketplaces of ideas, Oreskes says.

“And they promote these ideas that most Americans don't agree with, and that the facts of history don't support, but because it's what they want.

“And so, we show how these ideas become very influential. And of course, today we're seeing this in spades with billionaires having really taken control of huge amounts of the cultural space in American life, huge amounts of the intellectual space and universities.”

America’s antitrust laws, brought in the rein in the power of late 19th century monopoly capitalists have been watered down since the ideas of Friedman have taken hold with policy makers in the US, she says.

“One of the things that comes out of the Chicago School of Economics and again, this is a program that is supported financially by these American capitalists, is an argument against antitrust enforcement.

“The United States economy was really strangled by monopolies in the late 19th century by people we refer to in hindsight is robber barons, The John D Rockefellers and JP Morgan's of the world, who amassed massive fortunes and then use those fortunes to distort the political process.”

The Sherman Antitrust Act was passed to prevent monopoly because of its damaging effects on competition in the capitalist system, but also because the damaging effects on the political system, she says.

"But in the hands of the Chicago School in the 1960, and ‘70s, this argument gets completely eviscerated.

Ronald Reagan pushed a low tax agenda. Photo: DON RYPKA

"And a group of Chicago School economists make the argument that actually monopolies might be a good thing, because it's a kind of social Darwinist argument. They argued that monopolies are the companies that have won out in the Darwinian struggle for survival, and therefore, they must be the best companies.”

This argument has held sway in American politics for 40 years, she says.

"The Justice Department tried to bring antitrust enforcement against a number of highly monopolistic industries like the airline industry, and when they did judges threw out the cases, quoting the Chicago school, so this is a very tangible case where we can show how businessman supported a particular kind of academic argument, that argument influenced judges and it had real impacts in American life.”

The move against higher taxation was also promoted by the Chicago school and its adherents, despite there being little widespread public support for it, she says.

“Under President Dwight Eisenhower, who was a Republican, the marginal tax rate was over 90 percent.

“But actually, polls show the American people were pretty happy with the balance that we had. But in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Ronald Reagan, representing the interests that we talked about in the book, and with direct financial connections to in this case, the electricity industry begins to push this idea that taxes are too high, the idea of supply side economics, and it was not based on any empirical evidence that high taxes were strangling the economy.”

The evidence shows this to be a failure, she says.

“It was really a theoretical argument about how lower rates of taxation could benefit the economy.

“And so he [Reagan] pushes this idea through not because the American people are demanding it, because he and his allies are pushing this idea. And it's tried and failed; supply side economics actually hurts the economy of the United States. It leads to lower revenues to the government, and then what begins to happen is because the government is being starved of funding, then it is less efficient.

“And what we've seen in the United States in the last 40 years, the government has been inefficient and government agencies often can't do their job probably because they have been starved for funds, because of the market fundamentalist ideology that says the government's the problem and markets are the solution.”

Naomi Oreskes is a professor of the history of science at Harvard.