At seven years old, Suzanne Heywood set sail with her family on a three-year voyage around the world. Three years turned into a decade, with little formal schooling and many tensions between Heywood and her parents.

It all ended in Aotearoa, with a teenage Heywood looking after her younger brother and her Dad’s business. This unusual childhood is the subject of her new memoir Wavewalker: Breaking Free.

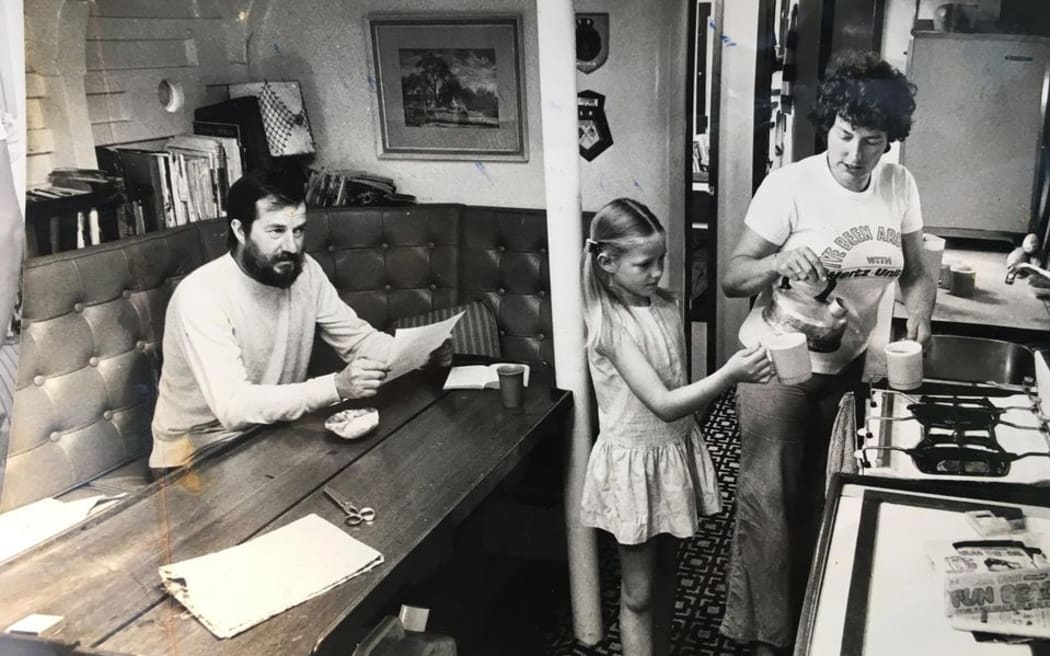

Suzanne Heywood with her parents, getting a cup of tea on board Wavewalker Photo: Suzanne Heywood

In the first year of the voyage, in the Indian ocean, they were hit by a terrible storm, she says.

“I'm a small child, I'm seven years old, a seven-year old girl down below deck, and I'm thrown up against the ceiling of the cabin, against the wall of the cabin, I fractured my skull, break my nose. And then of course, we almost sink.

"The boat starts filling up with water and we keep pumping. We have two crew members on board. They're pumping, my parents are pumping.

“Three days later, we make it to a tiny atoll in the middle of the Indian Ocean, where I receive multiple head operations without anaesthetic to try and fix the damage from the accident.”

Luckily the atoll had a tiny French base, and a doctor, she says.

“It had a doctor who had a very, very small medical facility, but unfortunately didn't have the ability to do anaesthetic for these operations.

“So, I had to endure them without anaesthetic. So, it really was for me, the whole thing, the wave, the aftermath and the operations on this island something that haunted me for years afterwards.”

The hematoma from the skull fracture would have resulted in brain damage without the operations, she says.

Life on board the boat was pretty grim in other ways, she says.

“I'm afraid it was quite a sexist environment. I was expected to work below deck, cooking and cleaning.”

Her relationship with her mother started to deteriorate as well.

“I'm not the only daughter who's had a very difficult relationship with her mother. But what makes this interesting in a way is we're trapped on this boat, and we can't get off.

“I have no friends, I have no one to contact. And the trip just keeps on going, for year after year after year.

“So, the relationships on the boat become very intense, and there is no way to escape.”

She was desperate to get an education, but when they moored up in Hawaii for a couple of years, her parents didn’t want her to attend the local school, she says.

“I was desperate by that point to get an education and desperate to make friends. I did go to Sunday school for a while, just for a way to make friends, and I made some friends in the boat yard.

“But it was very, very difficult. I suspect there were probably problems around our immigration status that made it difficult. Also, the schools would have been costly. There was some reason anyway, we couldn't go to school.”

She and her brother did attend school for about a year in Australia, she says.

“Which was fantastic, and I made friends there. And then I tried to keep in touch with those friends once we kept sailing again, by writing to them every time we got to a port and trying to get letters from them.

“So, I tried in the best way that I could to kind of make and keep friendships, but effectively I was completely isolated for most of the time that we were sailing.”

Suzanne Heywood Photo: supplied

Her parents were both teachers and intended to school on board.

“My mother did some of that for the first couple of years. When we when we first left England, she had a whole stack of worksheets, just maths and English. And she did do some of that with us, not when it was rough on board, when the weather was rough, and not when we were in port.

“But from time to time, when we were at sea she absolutely did. But that was only really for the first couple of years. And then we got through most of the primary curriculum.

“And she didn't feel that she wanted to do secondary education. So, after that, we didn't really get very much schooling for quite a long time.”

She enrolled at a correspondence school in Queensland and tried to keep studying that way.

“Of course, it's pretty tricky if you're on a boat, because you don't have an address. And this is, of course, pre-internet. But every time we got to a port, I was sending off lessons trying to get them back. And one way or another that is how I ended up getting myself in education. But it was a very tricky way to do it.”

Heywood says her parents were extreme, even for the times, in their need to follow their dreams no matter the consequences for their children.

“I've obviously talked to many people about their childhoods, people of similar age to me, I'm 54. And my parents were very extreme.

“I mean, to put your kids on a boat for a decade, without really any proper provision for schooling, for friendships, to do very, very dangerous trips.”

The experience was more negative for her than her brother, she says. He doesn’t agree with her all her recollections of the time spent aboard the boat.

“It is quite possible for siblings to have very different views. I also think that that sort of childhood is much more suitable for a boy than for a girl.

“As I say, my parents, I'm afraid, had very sexist views on roles on the boat, I was expected to cook and clean down below and we took paying crew on board. So, we were a bit like a floating hotel, particularly for the last six or seven years on the boat.

“I was expected to work down below for several hours a day, which my brother wasn't. My relationship with my mother was very, very, very difficult as people will find as they read the book, my mother and brother had a much better relationship.”

Photo: Harper Collins

Her mother died as a few years ago, but they never reached an understanding about her experiences as a child.

“I met her in 2015, which is when I started writing the book, and she was very angry. And she demanded that I shouldn't write the book, which was clearly because she felt that she wasn't going to come out of it very well.

She and I sat down one day, and she asked me what it was that I hadn't liked about my childhood. And I went through some of the some of the issues, she refused to discuss them with me, sadly. And then about nine months later, she died, she left a letter for me. I mean, she, died very unexpectedly, it was very shocking, and very sad, particularly for my father.

“But the letter, I have to say, was very uncompromising. It basically said that, she didn't like me as a child, she was relieved when, I left the boat, and really not really accepting any of the perspectives that I had.”

Her time aboard the boat came to an end when her parents left her and her brother in New Zealand and continued sailing. Her brother enrolled in a school, she was expected to look after him.

She and her brother, 16 and 15 respectively, were living in a bach overlooking Lake Rotoiti, her parents only visiting twice in nine months.

“I was instructed that I had to look after my brother, I had to cook and clean as I'd been expected to do on the boat.”

She was isolated and without adult guidance, she says. In desperation she rang a child helpline and was advised to make a friend, someone she could talk to.

“I did, I joined a club, Aikido, I found a girl who was living in a campervan at the bottom of the road. So, one way or another I got through that time. But it was very tough, despite the fact that it was an incredibly beautiful place.”

Always academically inclined, she decided she would go to university, and she wrote to all the universities she had ever heard about, often guessing their addresses. Most wrote back and said they had no places for her, but Oxford offered her an interview.

“I got a job kiwifruit picking, and that gave me about half my air ticket to go back, I managed to get my father to pay for the other half to get back to England.

“And at the end of that year in New Zealand, I got on a plane and went back and just bet everything on getting this interview to work and getting my place at university.”

It worked - and Heywood went on to forge a successful career and have a family of her own.

She got to the point in her life when her own children were the same age as when she was struggling on the voyage and she had an overwhelming need to go back and write about that time, she says.

“It operates on kind of two different levels, you're in such a wonderful place in South Pacific in particular, where we spent many years, and then of course, New Zealand.

“But the relationships on board are so difficult, and just, you know, unravelling, all of that is fascinating.”

Heywood is estranged from her father, who has written his own account of the voyage.

“One of the things I've learned, as I say, I’m 54, is you do have the ability to choose who you want to spend your time with in life.

“And I think it's sad that I'm not in contact with my father. But I have so many wonderful friends. I have all of my late husband's wonderful family. I have my kids, so I have many, many people in my life who I'm very happy to spend time with.”

Heywood's last book was the bestselling What Does Jeremy Think? an account of the life of her late husband Jeremy Heywood, British cabinet secretary and confidant of four prime ministers.

She now works with charities involved in getting children, and particularly girls, access to education in Africa and Afghanistan.