American novelist Richard Ford Photo: Supplied

For writers, mild dyslexia comes with "a whole bunch of benefits," says Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist Richard Ford.

"I read slowly so I am aware of qualities in language that I wouldn't be aware of otherwise. I hear sentences better, I see how words look on the page, I count syllables, I hear sounds. So there is a good side to it," he tells Kim Hill.

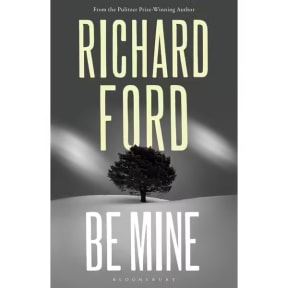

Ford has just published Be Mine - the final book in his series about the writer and real estate agent Frank Bascombe. The series began with The Sportswriter in 1986 and Ford won the Pulitzer Prize for the 1995 Bascombe novel Independence Day.

He talks to Kim Hill about dyslexia, death, writing and the last documented adventures of Frank Bascombe.

Ford says that he didn't plan to continue writing in Frank Bascombe's voice after The Sportswriter but Bascombe seemed to have more to say.

"I thought I was a 'one book' kind of a guy, that you wrote a book and you used up all your resources that book demanded and then you went on to some other book that you couldn't even anticipate when you wrote the first one.

"But when I got around to thinking about writing a subsequent book to The Sportswriter, I realised that all of the notes that I was writing in my notebook - which is how I compose books - are in what I identified as Frank's voice.

"I thought, 'Oh, Christ, you're not that ambitious a writer, and people will just think that you're rewriting the first book'. But after I kept generating notes and generating sentences that were in Frank's voice 'I thought to myself, dude, come on, you're being given something that you just shouldn't deny. You've been given a voice that readers will participate in and that they'll read with pleasure and with edification, so don't just fly in the face of what you've been given.' So I sort of backed into it that way."

Photo: Supplied

In Be Mine, Ford sends Frank and his terminally ill 47-year-old Paul on an "absurd" visit to the Mount Rushmore rock sculpture after Paul has spent time in a medical clinic.

The freedom to choose what his characters get up to is one of the more pleasant elements of writing a novel, he says.

"I probably thought at some point 'Why are the hell are they going there?' and the answer to that question is because I made them go there. And I tried to make it seem reasonable and essential and plausible.

"You say to yourself, all right, I'm going to take them there. That's what I'm gonna make my characters do. And then you get them there. And you describe the place and you try to make it visible. And then you subject Paul to it, and you have to dream up what the hell he's gonna think, what he's gonna say."

Be Mine was a tougher book to write than the previous Frank Bascombe novels, Ford says, partly because of the rigorous 'sensitivity editing' now required for novels in the US.

"You have to go through these ridiculous sensitivity edits in which they go through and try to prune out all the words that somebody might take offence at, which is humiliating and not pleasant.

"They try to basically force you to take words out and take scenes out and take events out that they think might offend someone. And you have to just fight them."

One mention Ford was asked to remove from Be Mine was a description of a blind man wearing "little Ray Charles dark glasses" and tapping his way along the sidewalk, seemingly to avoid falling off the curb.

"The editor said 'Oh, you have to take that out because it might persuade someone who's sightless that they are impaired'. I said 'Darling, if you're impaired that's just how it is'. So I didn't take that out. I won that battle.

"What you have to do is leave some egregious things in so you can, when you're asked to take them out, take them out harmlessly."

Ford tells Kim Hill that one of his own impairments - mild dyslexia - actually benefits his work with words.

"I still can't, when I'm editing something, see certain words on the page. I sometimes habitually leave the word 'not' out of a sentence that I'm typing or writing … I still read very slowly. I just can't make myself read more quickly than I could if I were reading aloud. But it's not been a hazard for me. I figured out how to deal with it.

"I read slowly so I am aware of qualities in language that I wouldn't be aware of otherwise. I hear sentences better. I see how words look on the page, I count syllables, I hear sounds. So there's a good side to it."

Ford, who grew up in "a little Podunk part" of the US - Jackson, Mississippi - says he's always been the sort of person who "looks at the horizon sort of longingly".

As a writer, he's been able to live in many places, sometimes following the work of his wife Christine, a "big deal" regional planner.

"I went off to college in Michigan, where I, thank God, met my wife, when we were 17 and 19. And we just didn't want to have kids so we lived all over, everywhere.

"We just went where Christine's jobs dragged us. And it was all over to California, to Chicago to Michigan, to Vermont, to New Jersey, back to New Orleans. Yeah, we just lived all over this huge continent."

The couple now live between New Orleans and Billings, "an old railroad oil town" in Montana where they enjoy pheasant and grouse shooting.

At 79, Ford says he's feeling like he wants to "squeeze life" as hard as he can but so far isn't freaked out by the idea of death.

"I guess you never know, do you? You can make all kinds of lavish claims for yourself about how brave you're gonna be when you get there. I think when you're there, you'll know right? I mean, but I don't pray. I don't pray on it … certainly don't pray, so I'm doing okay."

Having no way of knowing whether his books will stand the test of time, Ford doesn't concern himself with that question.

"Many things do not seem that absolutely eminent and essential at the moment. But I mean, I'll be gone, right, so whether they do or they don't, I can't really too much worry about them. What I can worry about is doing the best I can humanly do at that time I have your attention."

As to whether or not there will be any further Richard Ford novels to attend to, the writer is unsure.

"If a good idea came along for me, I would certainly jump on it. I would really hope it wasn't going to be 100,000 words, I'd be much happier if it was about 70,000 words. I'm available."