Author Trent Dalton Photo: Trent Dalton

Trent Dalton's autobiographical first novel Boy Swallows Universe was a massive hit all over the world.

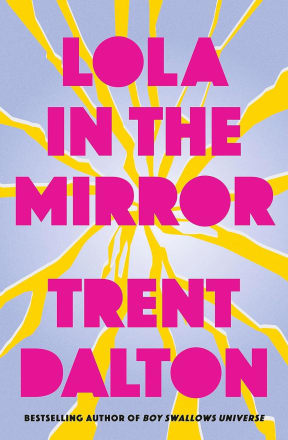

In his new novel Lola in The Mirror, the Australian writer brings to life the experience of homelessness in his usual compelling and strangely uplifting style.

Dalton says he could never have become a novelist without first prising his own traumatic childhood from "the pit of his stomach" in Boy Swallows Universe.

"I just had to get that out of my guts and face the truth of it and pay tribute to it. And once I did that, it genuinely unlocked all the stories."

In that book, the character of Eli, like Dalton, has a mum who falls in love with a Brisbane heroin dealer and ends up in prison.

"There were times when I was 12 years old, and kids at school would go, 'Hey, Trent, why is your mum not at tuck shop?' And I'd make up all sorts of stories about why she isn't. I didn't have the… courage or the wisdom to say 'Oh, well actually, she's just going through a really, really difficult time, and she's doing time behind bars. But that will just be a blip on a very complex radar that makes up her almost 70 years of life. And one day, she'll be the most amazing grandma to my two daughters and the most amazing mum to me.'"

Dalton says his stories have their origins in a Microsoft Word document, currently about 120 pages long, that's filled with ideas he's jotted down in that "nice little creative moment" between sleep and waking.

The ideas that make his spine "do a little dance" might become stories, and he leans towards those that "say something and might actually do something" to improve other people's lives.

"I know that's a flighty thing to think because it's like as if it's really ever going to change, but I've seen it too many times."

Photo: HarperCollins Publishers

In Lola in the Mirror, a nameless young girl and her mother are on the run from "monsters" and end up living in a clapped-out van by the Brisbane River.

Dalton says the book is a love letter to his beloved home city of Brisbane and he's proud that it shines a light on the increasingly common experience of homelessness.

"There's 12,000 people in my city who regularly seek homeless services, 120,000 in my country, and I just thought 'Well, okay, can I write a cracking yarn, a rattling yarn inside a world that matters?'"

The "great judgment" on homelessness is that it's the result of alcoholism and drug use, Dalton says. Yet while addiction does keep a person on the street, it's often childhood trauma and tragic misfortune that first sets them on the path to homelessness.

For his 2011 nonfiction story collection Detours, Dalton interviewed 20 regulars at Brisbane's iconic drop-in centre 3rd Space.

He says most spoke of a "detour moment" that first directed them towards the streets.

"You only get to know [those stories] if you choose to remove judgment and move close to that person. It's very hard to judge someone if you're really up close and you're actually seriously just sitting there going 'Tell me about what you've got inside, tell me what you're hiding in the pit of your stomach'."

Lola in the Mirror is all about the idea of whether you like what you see when you look in the mirror, Dalton says.

It can be profound to really look at yourself and reflect on the things you've done wrong while trying to remember the things you've done right.

He began doing this himself around the age of 12.

"I'd see great things, like I wanted to be Wally Lewis, captain of the Australian football team, right? But by the time I got to 16, I just wasn't liking what I was seeing in the mirror because I was wise enough to know … that the truth of [my life] was pretty sad. There was a lot of drink, and there's holes in the walls…

"I had this American baseball cap when I was a teenager and I'd pull it over my head. And if I did look in the mirror, it was genuinely to say like three words - eff you all. I was just really angry."

To address youth crime, we need to help young people see some hope for the future when they look at themselves in the mirror, Dalton says.

He totally gets it when people get locked into anger and despair, and remain there.

"It's so easy to stay in that place, and then suddenly you're 28 and you're still saying that to the mirror. And then, you know what, you're 55 and you're still saying that to the mirror."

Lola in the Mirror is dedicated to anyone who didn't jump in the river and also to anyone who did, Dalton says - the river being a metaphor for the weight of life that can easily consume or drown us.

'I make no judgments because the only thing that I had that I think some others don't, who do succumb, is love. I had a huge amount of love around me [as a child] … but also by the time I'm 20, I meet my wife. … It was that woman that made me - as cheesy as this is about to sound - smile in the mirror, and suddenly I liked what I saw in the mirror."

In his own honest mirror conversations, one "really deep question" that still comes up for Dalton is whether he did the right thing by his three "beautiful" brothers in writing such a confessional book as Boy Swallows Universe.

"In truth, they would probably prefer a world in which their youngest brother didn't put all this stuff in your book this way but I love them so much.

"They also understand that that's my way of processing all that because the alternative was bourbon and it's like that's a really positive alternative, writing, you know what I mean? It's a really positive way of doing it.

"The youngest brother, of course, is always an orphan, the one who romanticises it because I was the youngest … My oldest brother Joel sees the whole thing in a starker light, even a darker light because he was he was older and carried the weight of it more than all of us."

Grabbing a beer with his brother Ben after a Brisbane Broncos game recently, Dalton says he asked the usual question that comes up around midnight with one of his brothers: 'Mate, did I do the right thing?'

"He's like 'Stop it, you did and Dad would have loved it. I love it, we all love it. They're making a bloody TV show out of it, it's all good'."

Writing any personal truth you suffer consequences, Dalton says, and a bit of inner conflict is one of them. But he says the "flip side" of sharing honestly is no joke.

"You go to some book event and someone comes up and goes, 'Hey, I just want you to know that I read this book and I called up my dad. I haven't spoken to him in 30 years but I called up my dad.' And it's like, 'okay, well, that's a change. I know it's a small change but that's change.'

"I shouldn't discount the fact that [my book led to] someone picking up the phone and calling their dad, that's a small change that leads to some really great things."

Another time, a South Korean teen sent Dalton a message that read 'I just want you to know I'm 15 now and I read that book. And because I read that book I have decided to live to adulthood.'

"And it's just like, okay, It's all good. You know what I mean? … Let's just stick to that and if I'm speaking something to that young man then okay, I reckon Dad would be proud of that, as well."

Being kind to as many people as you can does change the world, Dalton believes.

"I think kindness and enthusiasm, if you can have those things as a human, then you're gonna be leading a pretty solid life."

Telling real-life stories via social affairs journalism is a job Dalton did full-time for 17 years and plans to continue doing. He says the work is good for the soul and also helps him get out of his own head.

"It gets dragged on so often, journalism, but I say it's the most incredible job in the world. It doesn't pay anything but who cares about money, life's not about that at all, it's about experience. And if you're looking for experiences, journalism is the greatest thing you could ever do. I just will never leave it because that one job gives me excuses for doing the wildest things … you suddenly got a reason to do something. So I'll definitely continue to do it for the rest of my life."

Watching his own early life depicted in the upcoming Netflix production of Boy Swallows Universe was an intense experience, Dalton says.

In the TV series - which one Netflix exec described as Sons of Anarchy meets Stranger Things - Dalton's childhood home in working-class Brisbane was meticulously recreated by the show's "amazing" production designed Michelle McGahey.

He says the "young wunderkind actor" Felix Cameron, who plays the central character Eli, was "an absolute avatar" of a young Trent Dalton.

"He's 12 years old and he's a bag of bones like I was as a kid. He's in the exact school uniform that I wore and he's got a piece of peanut butter toast … I walked right through the set, and I was weeping. And then this kid goes 'oh, hi Trent'. And I grabbed him and just hugged him and it was so strange. I said, 'are you okay? Are you good?' What I was saying was 'are you okay?' because I was sort of talking to myself, it was so strange and bizarre… it was just the most profound thing. He must have thought I was so weird. Like, why is this 44-year-old guy crying in front of me? I'm trying to do a scene here, mate."

While people on the Boy Swallows Universe TV set told Dalton he must have felt "on top of the world" seeing his childhood recreated, he only managed to pretend that he felt great about it for a few minutes.

"Then I turned to my wife, and I was just like, I need to get out of here, I need to go, and we just took off. So it was completely strange and yet the most beautiful thing to ever happen at the same time. And that's life, I guess."

In Lola in the Mirror, the girl is an artist who does ink sketches. At one point she speaks what Dalton says might be the "truest line" in the book.

"With a black ink pen, you cannot physically draw light. We get light on a white page from the darkness of the ink that we form around it … So our light comes from the darkness that is around it."