Photo: Cottonbro / Pexels

Facial recognition technology is helping fight crime but it's also making the internet a less safe place to put your face, says New York Times tech journalist Kashmir Hill.

"We live in a world now where there are so many companies looking at the public internet as a source for data, for text, photos or videos. [Content you've posted] will be scraped if it's on the public internet and it may one day turn up somehow in a way you don't expect."

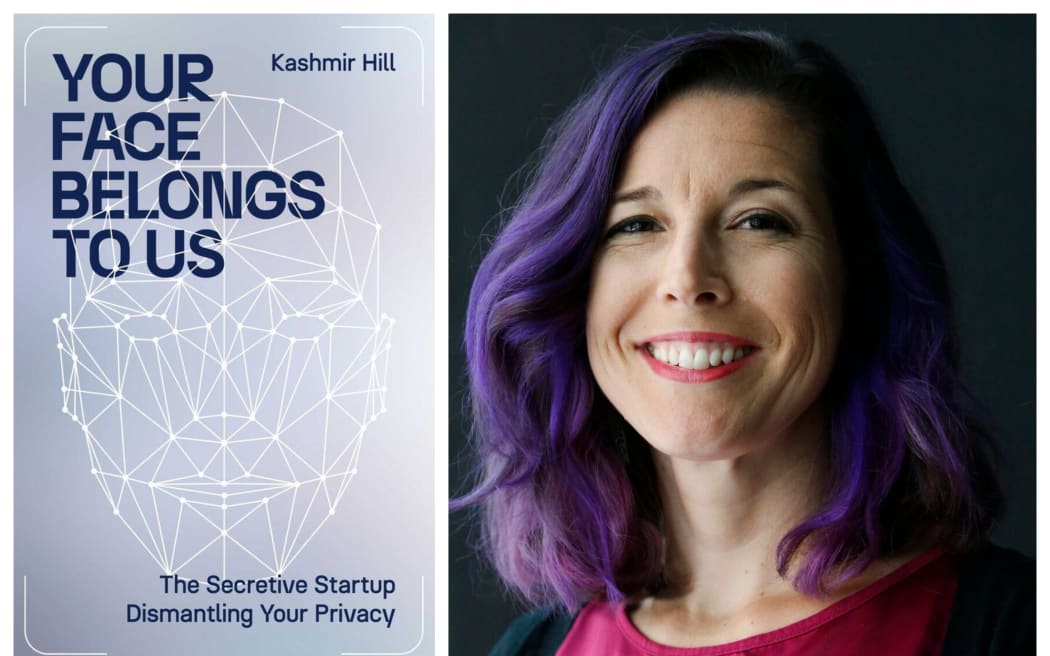

Kashmir Hill is the author of the new book Your Face Belongs to Us.

A couple of years ago, Kashmir Hill spoke to Saturday Morning about the facial recognition software tool ClearView AI, which is used by law enforcement agencies and governments around the world.

With over 30 billion faces in their database, ClearView AI's algorithm is now incredibly accurate at finding or identifying an individual by their face, she says.

It's easy to see the appeal of this tool to security forces such as the US Department of Homeland Security who recently subscribed to ClearView AI after it helped them identify a child abuse perpetrator via his appearance in a group photo posted to Instagram.

"The ability to be able to find a fugitive in real time or if a child is abducted, being able to look for that child's face or the abductor's face, finding wanted persons ... there's a real appeal to that and a push for that. But once you have that infrastructure in place, that means that you can track anyone."

In China and Russia, officials are using ClearView AI to identify not only protesters and dissidents, she says, but also people guilty of very minor infringements.

"In China, it's used to automatically ticket people who jaywalk. It's been used to name and shame people who wear pyjamas in public … They rolled out facial recognition technology in a public restroom in Beijing. You have to look into a camera to get a certain amount of toilet paper because they were dealing with toilet paper thieves there … I don't think most of us want to have to look into a camera every time we want a few squares of toilet paper."

Photo: Earl Wilson

The story of ClearView AI is an example of how anyone can build quite powerful software with tools now openly available online, Hill says.

She was amazed to discover the humble background of the company's founder, Hoan Ton-That.

"I thought the person who built it must be just, you know, a technological genius, someone who was so accomplished and incredible … and then I meet Hoan Ton-That and his experience is making Facebook quizzes and iPhone games and an app called Trump Hair. He was technically savvy but he was not, you know, a rocket scientist.

"[In developing ClearView AI], Hoan was just relying on code and algorithms that were essentially being shared on places like [software development platform] GitHub. I think that is the scarier idea, that we are making these kinds of technologies available to anyone to do what they will."

ClearView AI wasn't specifically designed to assist in law enforcement, Hill says.

"They were just trying to figure out 'okay, we've made this technology that can kind of recognise anyone. Now let's see who will pay for it.' And it just happened that police were the right customers and were the ones willing to pay for it."

Working with the American police has been a very effective defence for ClearView AI's decision not to comply with privacy laws outside of the United States, she says.

"They really just wanted to sell it to anyone who would buy it but they have evolved into using it for security purposes. So that's kind of been a Get Out of Jail Free card for them in terms of [avoiding privacy laws in other countries]."

Without adequate regulation, AI tools such as facial recognition software can too easily fall into the hands of "very radical actors" and be used to cross ethical and moral lines, Hill says.

While banning mass image databases created without individual consent would require global cooperation, she says that on an individual level we're all wise to be conscious of the potential risks of sharing images of ourselves and our children online.

"I encourage anybody who's posting to the internet to think about this. Is there some real advantage to putting photos and videos on the public internet? Because if there is not, I really think you should be doing it from a private account that's only available to friends and family or just sending messages directly to people, not on the public internet.

"We live in a world now where there are so many companies looking at the public internet as a source for data, for text, photos or videos. [Content you've posted] will be scraped if it's on the public internet and it may one day turn up somehow in a way you don't expect. I'm really a proponent of being more private in terms of what you make accessible."