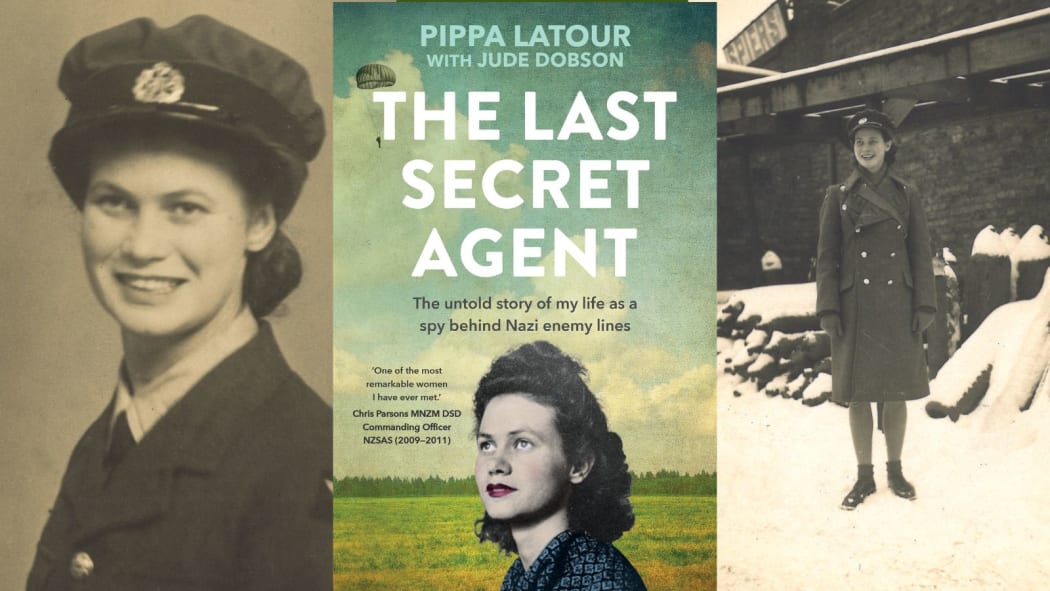

Photo: Allen & Unwin

The incredible story of Phyllis "Pippa" Latour, who was an undercover spy during World War II, is being retold by an award-winning New Zealand producer.

Latour parachuted into occupied France in 1944 while on her mission, but for decades she told no one - not even her family - of her undercover feats.

Before she died last year in Auckland, at the age of 102, she was the last surviving special operations agent in France to get out alive after its liberation in WWII.

New Zealand writer Jude Dobson shares the story in a new book, The Last Secret Agent: The untold story of my life as a spy behind Nazi enemy lines.

Dobson formed a close bond with Latour before her death, documenting her story.

This story contains disturbing details.

Latour was highly decorated and the last remaining female member of F-section, the branch of the special operations executive in WWII which organised operations in France.

Members gathered crucial intelligence about the Germans' movements in France, and also cut railway lines and telephone cables, forcing the Germans to send their messages over the airwaves, allowing them to be decoded in England.

Latour was parachuted into Normandy ahead of D-Day.

"Her job was a wireless operator," Dobson told RNZ's Sunday Morning. "And unlike a lot of the others who were stationary, she had 17 different sets around about a 100km area, so her job with her Russian courier ... they would go and report on German positions.

"Her alias was a 14-year-old girl selling soap... because the [German soldiers] apparently hated their soap, it was like sandpaper, and she had the lovely goat's milk soap. And she would report on where they were, and of course that was a bit of a death sentence... the next thing the bombers would come in."

New Zealand's member of parliament Judith Collins (left) and Phyllis Latour Doyle look at the Knight of the national Order of the Legion of Honour award she received from French Ambassador to New Zealand Laurent Contini in Auckland on 25 November, 2014. Photo: AFP / Michael Bradley

While she was in France, she was constantly in danger and on the move. She foraged for food and often spent nights outside in a forest, not wanting to put those in safe houses in danger.

She had many close calls, including searches at checkpoints with the radio codes sown into a shoelace used to tie her hair up, radio parts hidden under a full commode which was emptied and examined during a search, and a German soldier who fired into the ceiling of the place she sourced the soap from, in case there had been anyone hidden in the ceiling.

Some of the women from F-section who were caught died horribly. They were not covered by the Geneva Convention of war, and many were tortured and executed. Latour herself did not come through unscathed, she was raped by German soldiers before an officer stepped in and stopped it.

And during her time in France, she witnessed many civilians executed.

"She sent 135 messages in her time there, then she was overrun by the Americans," Dobson said. "Even then getting out to Paris was equally horrendous. She walked to Paris - took her two months.

"She was a smart woman, had her wits about her."

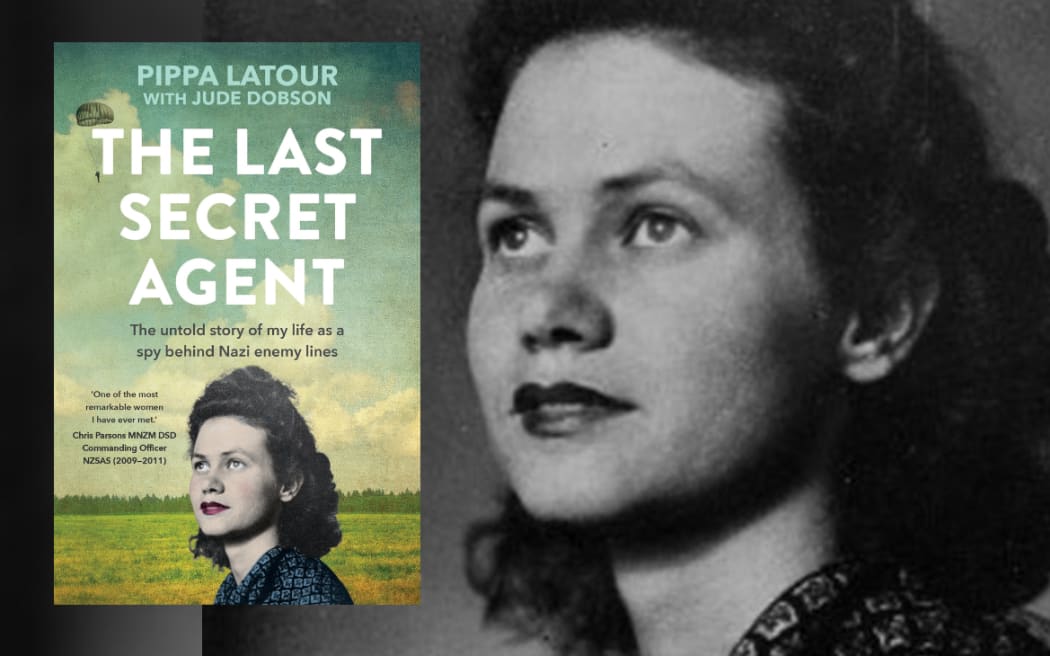

Photo: Allen & Unwin

Latour was born in South Africa, and had a British mother. During her childhood in the Belgian Congo her family moved frequently. "She picked up languages like a sponge ... she learned to shoot a gun at 7, and morse code, maths, algebra".

During training for special operations she was noted as being good at rope climbing, which she put down to climbing vines while often playing with monkeys as a child. She attended a finishing school in Paris, where she had polished up her French.

Before talking to Latour, Dobson had already interviewed some of New Zealand's last surviving pilots who flew during the war.

"That generation ... they were all young people once... and they did some pretty extraordinary things and I guess I just wanted to shine a light on it," Dobson said.

Through most of her life, Latour had intended to take her experiences with her to her grave, but changed her mind after her sons came across clues there was more to her story.

"I actually think she had PTSD ...In our first interview, she said to me: 'War wasn't pretty, and why would I want to talk about it or remember it?' She had quite a few nightmares."

So Dobson felt honoured to have been entrusted with the job.

"She was a remarkable woman... I really loved talking to her, it was a nice weekly date and ... I'd take out my cheese scones. She was a straight shooter, and she was extremely patient with me."

Sexual Violence, where to get help:

- NZ Police

- Victim Support 0800 842 846

- Rape Crisis 0800 88 33 00

- Rape Prevention Education

- Empowerment Trust

- HELP Call 24/7 (Auckland): 09 623 1700, (Wellington): 04 801 6655 - push 0 at the menu

- Safe to talk: a 24/7 confidential helpline for survivors, support people and those with harmful sexual behaviour: 0800044334

- Male Survivors Aotearoa

-

Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) 022 344 0496