Photo: Flickr / Hani Amir

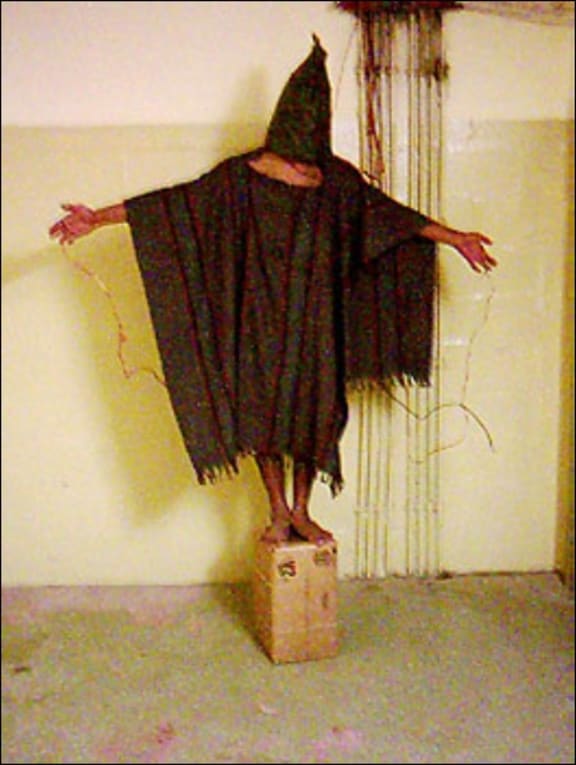

Detainee with bag over head, standing on box with dummy wires attached, under threat that stepping down from the box would cause his electrocution. Abu Ghraib 2003. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

One of the most disturbing images of the so-called War on Terror which the USA initiated after 9/11 is that of a Muslim prisoner in an Iraqi detention centre, hooded, standing on a box, which arms outstretched. He is being tortured in a prison run by the USA Army, and supervised by the CIA.

The author of Draw Your Weapons, Sarah Sentilles, talks with Jo Randerson.

Sarah Sentilles: “I remember the first day I saw the most iconic image now that is that picture of the man on the box, with the hood over his head, standing with his arms out. And I thought 'I need to change my life.' I had that immediate response of confronting evidence of American violence against the other.”

Photo: Random House

“And I realise now it was only my own privilege that made me think it was new. The United States has been torturing for as long as it has existed. But what interested me in part was that they were being called crucifixion images.”

“I had been in the ordination process and I’d exited it. And I wanted to understand what that narrative of salvific violence was doing. What kind of work did it do if you put it on the bodies of Muslim men being tortured by Christians,” asks Sentilles.

“What’s going on here? Would that make people think that torture is violence that does good and saves the rest of us? Jesus’ torture on the Cross is talked about as if it does something good for us. It reunites us with God.”

“So if people have that view of that kind of violence, would that make them think torture is divinely ordained? Or, would having the body of a naked tortured man at the centre of Christianity make people recognise those figures as somehow divine and in need of our help? That we needed to stop torture.”

“I wanted to understand that. I was writing my dissertation on imagination at the time so I decided I needed to write about those photographs instead and changed my dissertation topic. My supervisor quit so I had to teach myself photography theory and ethics, and visual culture, and try to figure out how photographs work and what they are.”

World Press photo exhibition, 2012 Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Gonzalo Malpartida

Jo Randerson: “I was raving to my friend on the street about your book [Draw Your Weapons] and she was saying she worked at where the World Press Photo exhibitions came and she was always really unsure about the exchange that was happening there. People in a privileged society were coming in and looking at these pictures of people in terrible pain. What is going on here?”

Sarah Sentilles: “I change my mind every three years about how pictures work. When I first started looking at images of violence and reading about them, I understood they were complicated. Sometimes these images that we can hold close on our phone or in a museum or on a computer screen, actually create distance between you and the person in the picture.”

“That apparent proximity is false. It’s like ‘oh, death happens over there, war happens over there, how sad for them.’ I was also wrestling with this idea that when we see images of pain, we’re very good at having emotional responses, and somehow our emotional response makes us think, ‘I’m a good person. I felt upset.’ But we don’t know how to translate emotional response into concrete political action on behalf of the people in the pictures.”

More reading

Sarah Sentilles talks to Kathryn Ryan

Sarah Sentilles in conversation with Lloyd Geering

About the author

Sarah Sentilles Photo: Gia Goorich

Sarah Sentilles is a writer, teacher, critical theorist, scholar of religion, and author of many books, including Breaking Up with God: A Love Story. Her most recent book, Draw Your Weapons, was published by Random House in 2017.

Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Oprah Magazine, Ms., Religion Dispatches, Oregon ArtsWatch, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications. She earned a bachelor's degree at Yale and master's and doctoral degrees at Harvard. She is the co-founder of the Immigration Alliance of Idaho.

At the core of her scholarship, writing, and activism is a commitment to investigating the roles language, images, and practices play in oppression, violence, social transformation, and justice movements.

She has taught at Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland State University, California State University Channel Islands, and Willamette University, where she was the Mark and Melody Teppola Presidential Distinguished Visiting Professor.

Photo: NZ Festival Writers and Readers

This audio was recorded in partnership with 2018 NZ Festival Writers and Readers at Wellington's Michael Fowler Centre. The next festival is scheduled for March 2020.